Why football and politics do sometimes mix

- Published

It is 1983. Corinthians enter the Morumbi Stadium, where they are to play in the final of the local Championship against powerful rivals Sao Paulo.

In the hands of the players, a huge banner says: "Win Or Lose, But Always With Democracy", a reference to the dwindling strength of Brazil's then military dictatorship.

The players were reflecting a spirit gradually taking over the country, culminating in the political campaign "Direct (Elections) Now", in 1984, in which millions of Brazilians demanded the right to vote for their president.

On the pitch, democracy and football merged to energise that desire, and civilian government was restored the following year.

The story is told in a Pedro Asbeg-directed documentary, Democracy in Black and White, which is due to be released next year.

Asbeg interviewed personalities from the world of football and beyond it, such as former presidents Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the writer Marcelo Rubens Paiva, and publicist Washington Olivetto.

They shared their views on the importance of Corinthians - as the most popular football team in Sao Paulo - in helping pave the way for the restoration of democracy.

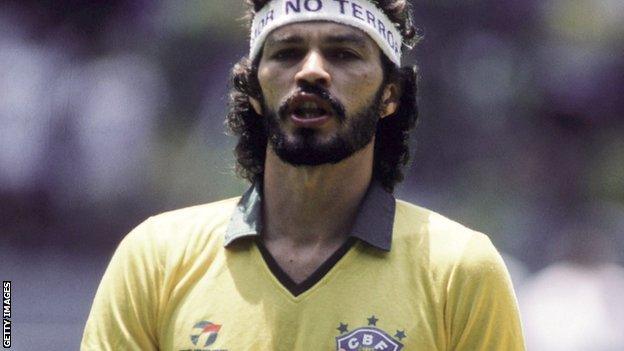

The film also shows the genesis of a star known for his genius on and off the football pitch: Socrates.

"The period from 1982 to 1984, the so-called Corinthians Democracy, is unique, there is nothing like this in football history," Pedro Asbeg told BBC Brasil.

"Starting with the return of Socrates from the World Cup in Spain and up until mid-1984, when the amendment of the 'Direct Elections Now' campaign was overturned by congress and Socrates, disappointed, leaves Brazil to play in Italy."

In fact this was only a temporary setback - a civilian-led government was restored in 1985, despite the defeat in congress, and direct elections would follow.

Asbeg has directed several short films about football, most of them about Flamengo, the much worshipped team he also supports.

Democracy in Black and White features another phenomenon associated with the efforts to restore democracy, the so-called Rock Brazil, a movement backed by the rebel football stars such as striker Walter Casagrande and Socrates himself.

The film highlights songs from that period such as "Inutil" (Useless), by the band Ultraje a Rigor, questioning people's inability to speak out or fully exercise their vote, and "Tedio com um T bem grande pra voce" (Boredom with a pretty big B for you), played by Legiao Urbana, a portrait of rebellious punks in the capital Brasilia.

"The film shows how this combination of football, politics and rock and roll changed the history of the country", adds Asbeg.

Former presidents Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Lula agree with the director.

For Cardoso the "exuberance" inspired by the Corinthians Democracy accelerated the pace of change, given the capacity of football to mobilise crowds.

Lula describes the period as the "Golden Age of Corinthians", recalling that victory on the football field showed Brazilians the importance of voting as exemplified by the system of player participation which was implemented at the club.

THE KICK-OFF

Corinthians had been in crisis in 1981.

The team had been relegated to the Silver Cup (equivalent to the second division) and was out of Sao Paulo Championship finals.

The newly elected president of the club, Waldemar Pires, was closely linked to his controversial and all powerful predecessor Vicente Matteus, but he felt the pressure from the fans for results.

Gradually, Pires gave way to the growing militancy of players.

Later that year, the team went on tour in Central America, and the players decided that two of their number - the star Paulo Cesar Caju and goalkeeper Rafael - did not share the spirit of the group, and should leave.

Pires then chose as director of football the sociologist Adilson Monteiro Alves, son of a former director of the club.

Alves allowed the players an even bigger say. He was "young, open-minded" in the words of Waldemar Pires, and supported the proposals of the more politicised among the players, such as Socrates and Wladimir.

"Corinthians was the perfect metaphor for the country's situation," says Asbeg.

.jpg)

Corinthians' final match in 1983

"It was leaving behind the authoritarian rule of Vicente Matteus... and its players were eager for more participation. This was true of the entire country."

This was a reference to 1982 when the country held its first general election for a government since the beginning of the military regime, though it still had a general as president.

"When the publicist Washington Olivetto heard of what was happening inside the club, he called it the Corinthians Democracy. The term stuck and helped Corinthians to make it out of the rut where it was stuck and to become a national club, which would be confirmed in the following decades," says Asbeg.

With the likes of Casagrande, Zenon, Juninho, Wladimir and Biro-Biro, and focused around the critical force of Socrates, Corinthians won the Sao Paulo championship in 1982 and 1983, something which had not happened for 30 years.

"I started to like it. Started feeling like a citizen", recalled striker Casagrande in the film.

Between the local league and the national one, the players decided the replacement for coach Mario Travaglini, who left the club to run Sao Paulo.

The choice was Ze Maria, a veteran player.

"Adílson called me and said there would be a meeting at Wladimir's home. Casagrande and Socrates were there too. Socrates said: 'We have heard what everyone has to say and we would like you to take on the post of manager', " Ze Maria told BBC Brasil.

"We were 10 matches from the end of the national championship and I accepted it. There was a great solidarity among us. And we ended up doing very beautiful football in the finals."

"EXCEPTIONAL CIRCUMSTANCE"

The sports commentator Juca Kfouri followed closely the Corinthians Democracy. He was next to Olivetto at an university seminar when the term was coined.

Kifouri, who also spoke to Pedro Asbeg in the film, says that in terms of sport, the Corinthians Democracy was a great success.

"That was very special. It happened during exceptional historical circumstances in Brazil and it was a happy coincidence that those unique agents combined at the same place and at the same time", notes Kfouri to BBC Brasil.

However Kifouri does not see a legacy from that period for current players. For him there is currently less participation and democracy, and football remains a reactionary area.

Nowadays, he says, "the players are puppets, pop stars, who worship money - superfluous and superficial culturally."

Studied by scholars in Brazil and abroad, the subject of books and now this documentary, the Corinthians Democracy paid the price often suffered by innovative movements, observes its director.

"In the elections at Corinthians in 1985, the group supported by the players was defeated, which led to a rebellion by the leading rebels, forcing the newly elected directors to leave the club through the back doors on election night", recalls Asbeg.

Around the same time, the Direct Vote Amendment was overturned by congress, leaving Brazil with another four years of government chosen by the Electoral College.

Despite receiving a large number of votes, the absence of 112 MPs meant that the amendment failed because it didn't reach the minimum number of votes for approval in the parliamentary session.

On and off the field it was not the result most desired in the Corinthians Democracy, although in 2012, Brazil is now a full democracy, able to reflect on this extraordinary story.

- Published5 December 2011

- Published7 October 2011