Jimmy Hill: Match of the Day host who changed football

- Published

Ex-MOTD presenter Hill dies aged 87

When Jimmy Hill moved from ITV to the BBC to present Match of the Day in 1973, the Radio Times announced the news by putting him on its cover under the headline 'Catch of the Year'.

There was a very good reason for the excitement: Hill, who died on Saturday aged 87, had revolutionised televised football as head of sport at London Weekend Television and he arrived at the BBC with the mandate of modernising Match of the Day.

He succeeded, helping to make it a national institution. As the face of the programme, he would go on to be one of the most recognisable TV personalities of the 1970s, '80s and '90s.

In the days when there were only three channels, the programme regularly commanded viewing figures of more than 12 million, about double its average now. And Hill became a cult figure because of his distinctive appearance as well as the forthright and occasionally off-the-wall views he expressed in front of the camera.

Hill was well aware of the programme's popularity, something former Match of the Day pundit Bob Wilson discovered during his decade on the show, from the mid-1970s onwards.

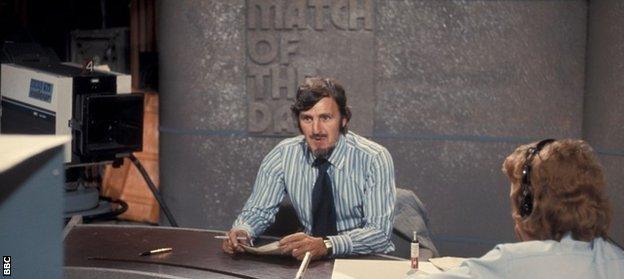

Hill was a presenter and analyst, who travelled to watch games then hosted Match of the Day live

"On one occasion, fire alarms rang out all around us in the studio," Wilson said in a book commemorating the programme's 40th anniversary in 2004.

"Jimmy looked at me and asked what I thought we should do. When I replied that we ought to get the heck out of there, he looked bemused and said 'no, no, the nation needs us', and he meant it!"

In total, Hill made more than 600 appearances on Match of the Day and remains the programme's longest-serving anchor, spending 16 seasons fronting the show.

When Des Lynam replaced him in 1989, he stayed on for another decade as a pundit. In total he worked for ITV and the BBC on nine World Cups (1966-1998) and eight European Championships (1968-1996).

Five essential Jimmy Hill moments

'Bearded beatnik'

When Hill joined Match of the Day, the limitations of 1970s technology meant he had to attend a game if he was going to analyse it. Back then, there was no other way to watch live - so he often used a private plane to get back to Television Centre in time for the show.

Not everybody agreed with his analysis, and he was not always taken seriously, but his long and distinguished broadcasting career was only a tiny part of the story of his lifetime spent in football - and the wider impact he had on the sport he loved cannot be underestimated.

On the pitch |

|---|

Full name: James William Thomas Hill |

Born: Balham, London, 22 July 1928 |

Before football: He worked at an insurance company and for a stockbroker after leaving school and as a clerk in the Royal Army Service Corps during his national service |

The player: An amateur with Reading after leaving the army, he started his pro career at Brentford in 1949 on £7 per week, which he supplemented in the summer by selling light bulbs and running a chimney sweeping business. Hill joined Fulham in 1952, in exchange for Jimmy Bowie and £5,000 |

Before he became a TV pundit, presenter and executive, Hill was a footballer-turned union leader dubbed the 'bearded beatnik' because of his willingness to challenge the system.

He received just one booking in his 12-year professional career and responded by writing to the Football Association demanding they introduce an appeal process.

A charismatic innovator and forward thinker, some of the ideas Hill helped make a reality included the abolition of the maximum wage, establishing a player's right to freedom of movement at the end of his contract and the introduction of three points for a win.

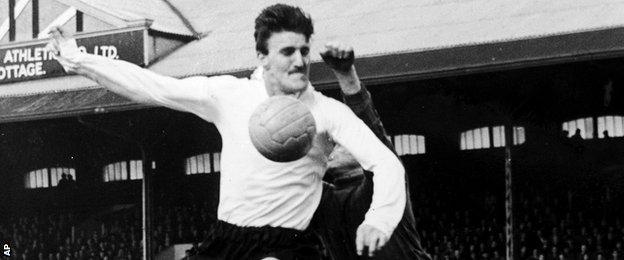

Hill's most prolific performance for Fulham saw him score five goals against Doncaster Rovers in 1958

He was also a pioneering coach, successful manager and inventive chairman.

Appropriately he was also a versatile footballer, playing in every position apart from goalkeeper during the nine years he spent at Fulham after joining from Brentford in 1952, although he was mainly used as inside-right, or deep-lying striker, to use modern parlance.

Hill worked as an FA coach while he was still a Fulham player

The son of a Balham milkman, he scored 41 goals in 277 games for the Cottagers but, other than his famous cameo as a stand-in linesman during a game between Arsenal and Liverpool in 1972,, external his time on the pitch was the least eventful part of his life in the sport.

Although he scored in every round of the FA Cup when Fulham reached the semi-finals in 1958, his most notable achievements as a player came after he was appointed chairman of the Professional Footballers' Association in 1956.

Hill campaigned to end the Football League's £20 maximum wage, threatening a strike before he succeeded in abolishing the ruling in 1961. Within months Johnny Haynes had become England's first £100-a-week player.

Hill briefs the press over the possible players' strike in the wages and contracts dispute

That same year, Hill's playing career was ended by a long-term knee injury, and his first book 'Striking for Soccer' was published.

In it, he advocated more major changes to the game, including a super league, winter break and regular midweek evening games played under floodlights.

Perhaps the most radical idea was the role he saw television playing in the game. Hill argued one game a weekend should be played live in front of the cameras on Friday nights.

He saw that idea bear fruit more than 20 years later, when with Hill as host, Match of the Day experimented with live games on Fridays during the 1983-84 season.

In the dugout and the boardroom |

|---|

The coach: Earned his FA coaching qualifications by the age of 24 and was running the same courses two years later. Took Fulham's pre-season training while still a Cottagers' player and also coached the Oxford and London University teams, and Sutton United part-time. |

The manager: In charge at Coventry from 1961 to 1967, winning promotion twice but never managing in the top flight. |

The executive: Coventry's managing director and then chairman from 1975 to 1983. Also spent time as Charlton chairman and part of a consortium that rescued Fulham from bankruptcy in 1987. |

Love affair with Coventry

Hill did not have to wait as long to implement some of his other suggestions, which also included better facilities and more entertainment for fans, after being appointed manager of Coventry in December 1961 at the age of 33.

His first act was to lift a 10-year club ban on players talking to the press. He demanded they call him 'JH' rather than 'boss' or 'gaffer', did not sign anybody older than 25, and introduced a scientific, analytical approach to training.

His appointment was the start of a long love affair with the club that, on and off, lasted 22 years and took in various roles.

During six years as manager, he took City from the bottom of the old third division and into the top flight, before leaving after securing that second promotion to pursue his TV career, initially off the screen.

In that time, with the blessing of former chairman Derrick Robbins, he overhauled Coventry's image with what became known as the 'Sky Blue Revolution' - changing their home kit from navy and white back to the colours they had last used half a century before, and introducing a nickname and club song to match.

He introduced English football's first electronic scoreboard, launched its first glossy match magazine, enticed fans to arrive well before kick-off with match-day radio and pre-match pop concerts. He also ran the club's own rail service for fans to get to away games.

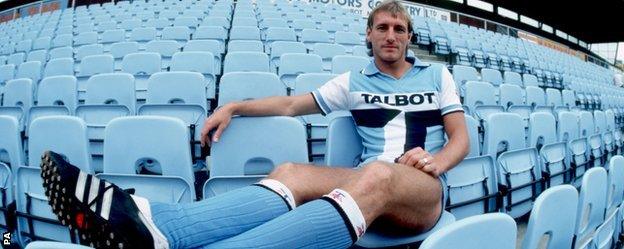

Coventry winger Steve Hunt in the club's 'Talbot' shirt just after Highfield Road became all-seater

He was also responsible for the first beam-back broadcast, in October 1965, when City's midweek win at Cardiff was watched by 10,295 fans at their own ground.

Hill's priority was to make the local community feel part of City's success - he made a point of using 'we' whenever he referred to the club - to the extent he considered exploding a huge firework or mortar shell on the half-way line to alert the whole of the city every time they scored, and only dropped the idea when he realised it would endanger the lives of fans and players.

"The idea was to cement the relationship between the club and our fans," Hill told BBC Sport in 2005, when discussing his innovations., external

"When you start to put your mind to things like that, what it's like to be a supporter and how you can make it more enjoyable for them, you realise there is not any particular cost in doing it."

On screen and in song |

|---|

The broadcaster: First worked as a pundit for ITV on the 1964 FA Cup final and part of the BBC panel for the 1966 World Cup. London Weekend Television's head of sport from 1967-1972 and deputy controller of programmes in 1972-73. Worked for the BBC from 1973 to 1999 on a variety of other sports as well as football and fronted Sunday Supplement on Sky Sports between 1999 and 2006. |

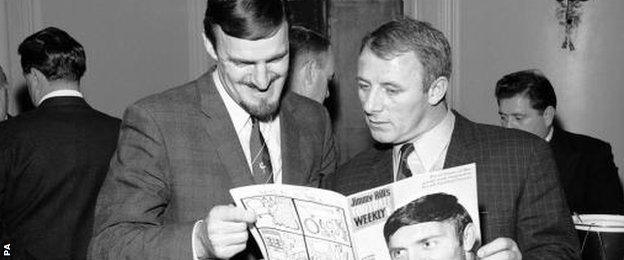

The author: As well as his 1998 autobiography, Hill wrote two books: 'Striking for Soccer' (1961) and 'Improve Your Soccer' (1966), had a regular column in the Daily Express and the News of the World and in the mid-1960s launched a magazine called 'Jimmy Hill's Football Weekly'. He also co-wrote Coventry's 'The Sky Blue Song' (1962) and penned 'Good Old Arsenal' (for the 1971 FA Cup final). |

'You can't be a hooligan sitting down'

Hill's managerial career ended by his own choice in 1967, when TV beckoned. He had wanted a 10-year contract to stay on as Coventry manager but was only offered five. He would be back, however.

Hill returned to the club in 1975, first as managing director, and later as chairman. More innovations followed.

He embraced sponsorship - notably by incorporating the 'T' logo of now defunct car company Talbot into Coventry's kit - and was responsible for turning Highfield Road into England's first all-seater stadium in 1981 with the slogan "you can't be a hooligan sitting down".

That idea was too far ahead of its time - and only lasted a matter of months thanks to rioting Leeds fans who ripped up the seats - but another of his proposals that year would have a much longer and larger impact.

Amid concern from fellow chairmen over sliding attendances, Hill campaigned for the introduction of three points for a win rather than two, with the reasoning that it promoted attacking, and thus more entertaining, football.

Within 14 years, every major league in the world had followed suit, and the system was also introduced at the 1994 World Cup.

Hill and Tommy Docherty at the launch of his magazine 'Jimmy Hill's Football Weekly' in 1967

By the start of the 1980s, Hill's television career was also in full swing. He had joined LWT as their head of sport in 1967 and immediately poached the BBC's Brian Moore, who would be the face and voice of ITV football for most of the next 30 years.

The introduction of technology like the first slow-motion replay device in the UK and a predictive computer nicknamed 'Cedric' helped ITV's 'The Big Match' outshine 'Match of the Day'. And more success came at the 1970 World Cup, when Hill was responsible for installing ITV's panel of experts in a studio at Wembley.

Hill went for outspoken extroverts like Malcolm Allison and appointed himself as presenter, and the result was TV gold. For the first time at a football tournament, ITV's audiences were bigger than the BBC's.

By the time he joined the BBC in 1973, Hill was approaching celebrity status. The same Radio Times that announced his arrival on its cover described him inside as "belonging in the classic mould of those sporting heroes beloved of boys' comics like Wizard and Hotspur".

He would help Match of the Day become a national institution, also bringing fame to commentators and co-hosts John Motson and Barry Davies. They would come into the studio to analyse their own commentaries and present news round-ups in the days where the show could only show highlights from two top-flight games each weekend.

Hill featured in the title sequence for three years from 1977, when a giant picture of him was cut up into 2,000 pieces and held aloft by schoolchildren at QPR's Loftus Road ground, which is adjacent to Television Centre.

'That's fame for you'

He remained outspoken as his TV career continued, and he was often controversial too. There was outrage from Scotland fans when he described David Narey's goal for Scotland against Brazil in the 1982 World Cup as a "toe poke".

He chose to play up to his supposed antagonism with the Scots in the years that followed, though he did apologise for his Narey remark on BBC Scotland in 1998. They were not the only set of fans to take offence, however.

Des Lynam recalled: "We were at a ground and all 30,000 people started chanting at him, but not quite in his favour. I asked him how he put up with it and he simply said 'that's fame for you'. He was not going to be beaten by a chanting crowd."

Hill left the BBC in 1999 and moved to Sky, chairing Jimmy Hill's Sunday Supplement, before leaving the organisation in 2006.

His footballing legacy was not forgotten when his media career ended, however. He received an award for his contribution to league football in 2009 and was inducted to the National Football Museum Hall of Fame with a special Lifetime Achievement award in 2010.

Coventry have remembered him too. In July 2011 a 7ft-bronze statue of Hill was unveiled at the Ricoh Stadium, after £100,000 was raised by fans.

.jpg)

A giant mural of Hill at Loftus Road featured in Match of the Day's opening credits

- Published19 December 2015

- Published14 December 2015

- Attribution

- Published28 July 2011

- Published19 December 2015

- Published20 June 2016

- Published7 June 2019

- Published2 November 2018