Confederations Cup: Rio de Janeiro slums offered rebirth

- Published

'Paradise is here, hell is here, madness is here, passion is here' - lyrics from singer and musician Francis Hime's Sinfonia do Rio de Janeiro.

This is not the Rio you will find in the guide books or see in Fifa's slick promotional videos.

There is no white sand here, no glamorous sun-worshippers and no palm trees swaying gently in the breeze.

Welcome to Penha, until recently one of Rio's most notorious and dangerous favelas, or slums. It was run by a drug gang, armed with an arsenal the police could not match. Cocaine was the currency and the local hospital would deal with an average of 120 bullet wounds a night.

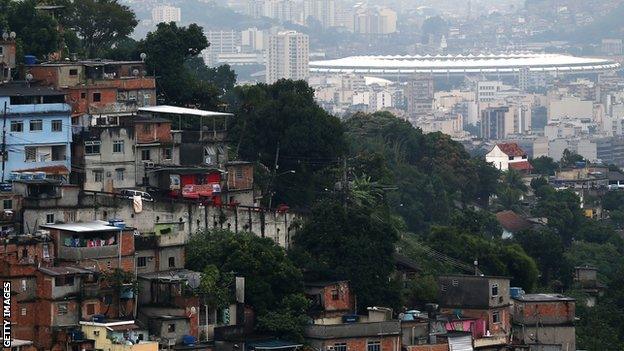

The settlement creeps up the mountains to the north of this vast, sprawling city, twisting and turning into the hills - brick shack after brick shack, stacked high into the heavens, defying gravity. The air is thick with the stench of sewage. Pigs and cockerels roam the narrow streets.

This is Brazil, however, where the 2013 Confederations Cup is currently taking place as a warm-up for next year's World Cup, so there is always a place to play football.

Twenty-two young children race around a dusty pitch in front of me. The match is carefree and chaotic but lit up by sublime flicks and tricks, goals and glory. Football is the escape here.

Nanko van Buuren watches from behind a metal fence. The Dutchman, a psychiatrist by trade, came to Brazil in 1987 to lift children away from organised crime and poverty. He has helped almost 4,000 children in 68 favelas since founding IBISS, external - the Brazilian institute for innovation and social health care - 20 years ago.

Football is the cornerstone of his miracle. "I started by talking to the drug soldiers and telling them they would be dead by 21 if they carried on trafficking," he says. "No-one had ever talked to these boys and explained to them there was another way - a way that did not involve organised crime."

Van Buuren is using football to change the way of life here. Some of the stories are scarcely believable.

Max, as he is known, ran Penha. He was a drug lord, a gang leader with the power to say who lived and who died. He is, as are the majority of Rio's drugs bosses, in his 20s. Few live much longer - it's a perilous existence. "Without football, I'd probably be dead," he says.

It is not every day that you spend a morning with a former Rio drug lord, but Max shakes my hand and smiles as we meet. He is 27 now, a wiry figure with a broad smile, cropped black hair and a tattoo of the word Jesus on his right hand. Drugs are no longer a part of his life. Football is.

Penha was "pacified" in 2010 as part of the government's programme to stop militias and drug gangs controlling the favelas. The process began with a "shock and awe" invasion by 1,200 heavily armed soldiers and 800 military police. Tanks, apache helicopters, rocket-propelled grenades and missiles were used. A fierce and brutal war ensued, broadcast live to Brazilians courtesy of the TV helicopters hovering above.

Some 26 deaths were reported,, external although the people here claim the real figure was much higher.

Behind the football pitch, the hills climb still higher. It was into these mountains that Max escaped when the military invaded. A meeting with Van Buuren brought him back into Penha, but in a very different capacity.

"We take ex-drug bosses, like Max, and ex-drug soldiers and show them how to coach football to the kids," Van Buuren says. "Here they are role models to show children that organised crime is not the solution."

David Shukman takes a walk through the streets of Brazil's largest favela, Rocinha

Max is a man reborn. "I could not feel emotion in the past," he says. "I was dead inside, a machine. Nanko saved my life."

With the favela taken, the government installed a Pacifying Police Unit (UPP), which now patrols the narrow streets, brandishing machine guns to restore federal law here. Drugs still exist on a lower level but the weapons have gone.

One of the rules in Van Buuren's programme is that only children who attend school can play football in the favela. When IBISS began, around 40% of the children went to classes. Now that figure is at 98%.

It is an incredible and heartwarming success story in the unlikeliest of places and Van Buuren is treated like a demigod here.

Always smartly dressed in his blue blazer, white collared shirt and black leather shoes, he has children swarming around him, and in the dilapidated concrete shack that doubles as the local bar they refuse to accept his money when he buys a round of drinks. He leaves the keys in the ignition of his 4x4, the doors open, valuables on show.

But he admits the old wounds will take time to heal.

"In this favela where we are now, there is no family that has not lost one of their own to a bullet," he says. "Many of the kids are still traumatised but we are using to football to help them cope.

"They are becoming educated, getting jobs - that gives you the strength to go on but there is still work to do. Many people don't believe it is possible to persuade ex-drugs bosses and ex-drugs soldiers to stay out of crime. We are showing it is but some won't be persuaded."

In contrast with the townships of 2010 World Cup hosts South Africa, the majority of which are located away from the city centres, many of Rio's 900-plus favelas sit cheek to cheek with some of the city's most exclusive neighbourhoods. Brazil's federal government wants to rid them of crime and violence before next summer's World Cup and the 2016 Olympics, when the eyes of the world will be on them.

"It is important that the world sees what is going on here," Van Buuren says. "It is important that people who come to the World Cup and the Olympics see the other side of society in Rio.

"I hope the whole world can help to change this crazy civil war that still exists here in Rio de Janeiro."

- Published17 June 2013

- Published17 June 2013

- Published16 June 2013

- Published17 June 2013

- Attribution

- Published12 June 2013

- Published3 June 2013

- Published31 May 2013