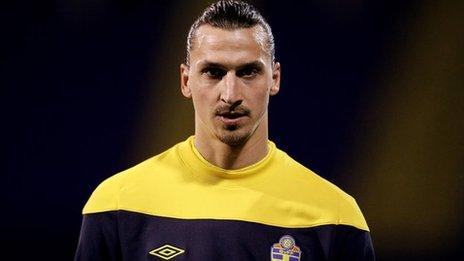

Zlatan Ibrahimovic: From teenage outcast to world great

- Published

- comments

Mourinho made me a lion - Ibrahimovic

Zlatan Ibrahimovic. You might have heard of him.

He is the footballer with the bad attitude and self-assured air of arrogance. He is the tall one who never plays well against English teams. He is the one who fights with team-mates and is a nightmare for his managers. And, oh yes, occasionally he finds a moment of genius.

A smile spreads across the familiar features of the 6ft 5in Paris St-Germain striker as he considers this popular perception of him.

"I read all the time that people think I'm arrogant," he says, settling down for our one-hour interview in Stockholm. "They say I am cocky, a bad character. I had that from a young age. But when they meet me, they say 'that image doesn't fit you.' Where I come from you never judge a person until you meet them. I would never do that."

So, who is the real Zlatan?

"I always put myself second - I like to make others happy," he explains. "Wherever I have played, I have won (nine league titles in the past 10 seasons with five clubs). But I only feel satisfied if my team-mates, the fans, everyone is happy. I have a big heart."

Is it true that he is hard to manage? "No. That is a picture someone painted of me that follows me wherever I go. If you talk to the coaches I have played for, the only one that would say maybe I was a problem was Pep Guardiola. (That is) if he has something to say, which I don't find he has."

More on that later.

Ibrahimovic is here to discuss his book - I Am Zlatan., external It is the brutally honest story of a boy who shook off the shackles of poverty and discrimination to become one of the world's great footballers, the captain of Sweden and a millionaire who won over the blonde from the right side of the tracks.

There are all the ingredients of a modern fairytale. It seems no punches are pulled, no words left unspoken and every aspect of his career is discussed.

The 31-year-old arrives for the interview almost two hours early, dressed in Sweden training gear and with his hair pulled back in a ponytail. He repeatedly apologises for a cough he has developed in recent days, asks if his near-perfect English is OK and he shares stories about his two sons.

He is relaxed, open, funny and generous with his time. None of this sits comfortably with the stereotype that has come to define Ibrahimovic in the minds of those who have never met him. Part of that is down to his own admittedly wild behaviour as a young man.

The son of a tough Croatian mother and hard-drinking Bosnian father, he grew up in the Malmo ghetto of Rosengard., external They were outsiders living in a parallel world to mainstream Sweden. His parents broke up when he was two and his household was a battleground - a place where you were more likely to get hit than hugged.

And he stole. In fact he stole a lot - bikes, sweets, cars, anything and everything.

"When we needed something we went to the shop and we went to steal," he says. "I had a particularly good relationship with the bikes."

One day he stole the postman's bike. "Ha ha, that was a great bike, a military bike," he remembers. Another day, he discovered that the bike he had stolen to travel the 5km to and from training belonged to his football manager. "He took it pretty well. He could have kicked me out but he laughed."

He held tight to football from an early age. On a small, dusty pitch in the estate, Ibrahimovic and his friends tried outrageous tricks and flicks, spins and shots. The lack of space meant you had to be quick with your head and your feet. Zlatan quickly found his calling.

"When we played football in Rosengard, it was all about putting the ball between people's legs, doing different things," he adds. "After every trick people were like 'oohhh' 'eeeyy'. It was all about who had the hardest shots, the best trick, the craziest move. I loved it."

His heroes were not Swedish, even after they finished third in the 1994 World Cup. He only had eyes for the brilliance of Brazil, studying the likes of Ronaldo and Ronaldinho watching how they performed their dribbles until he too could dazzle his friends.

"I did not watch Sweden, I never watched Sweden," he says. "I loved Brazil because they were something different. They touched the ball differently, like field hockey where you drag the ball. That was magic and it felt totally different to anything I had seen before."

School was not for him. "I've been at this school 33 years," his former headmistress said, "and Zlatan is easily in the top five of the most unruly pupils we have ever had. He was the number one bad boy, a one-man show, a prototype of the kind of child that ends up in serious trouble."

"I was rowdy, I was mental," the striker agrees. "I just had a hard time sitting still, I had ants in my pants."

Playing with fire? Ibrahimovic has never been afraid to voice his opinions and has criticised Guardiola

Until he went to secondary school, he had never seen people wearing shirts with collars. It was a different planet. One he could not fit into.

Ibrahimovic also found doors closing as he tried to pursue a career as a professional footballer. Even when he joined the city's professional club, Malmo FF, at the age of 17, the parents of one of his team-mates petitioned to have him thrown out.

"For me to succeed as a footballer was difficult because of my background," he explains. "But I was difficult too. At one training session I head-butted my team-mate. If I could put myself in that moment today I would say to myself 'don't ever do that', but I was an angry young man.

"The player got a letter from his parents and asked people to sign it to kick me out of the club. I did many stupid things, I made many mistakes, but I learnt from everything. I still make mistakes, I still learn from them. Nobody is perfect. I had a lot of walls to break through to get here."

Something changed around the age of 18. He began to realise football could offer him a future, a path away from his difficult upbringing. Ibrahimovic scratches the tattoos on both wrists and exhales deeply when asked if, back then, he would have believed he could achieve the things he has.

"When I look back and think where I have come from, who would have thought the guy from Rosengard would have done these things?" he asks.

"Who thought the guy from Rosengard would be the captain of the Swedish national team? Who thought the guy from Rosengard would break the goal records? I was never considered one of the big talents, never."

Ajax saw off interest from Arsenal, AS Monaco and Verona to sign the player from Malmo. After that came spells - and titles - at Juventus, Inter Milan, AC Milan, Barcelona and Paris St-Germain. Two managers have had the greatest influence on his career: Juventus coach Fabio Capello - "he gave me my winning mentality" - and Jose Mourinho - "[he] turned me from a cat into a lion, dragged things out of me at Inter that no one had done before".

He also praises Carlo Ancelotti, who managed him at PSG, describing the Italian as "the most fantastic man, almost like a father".

But his dream move to Barcelona ended in disaster and with a total breakdown in his relationship with Guardiola. "I had a dream to join Barcelona but now I think maybe you should keep your dreams instead of making them come true, because it could have destroyed me."

For the first few months in Spain, life went well, but then Guardiola stopped communicating. "I still don't know why, I may never," Ibrahimovic says.

"I tried to make contact with him - but he didn't want to speak to me, he was avoiding me. I walked into a room, he was sitting there drinking his coffee. But he got up, didn't finish his coffee. I thought: 'I'm not the problem, he is the problem.' But there were no words, no answers, nothing.

Ibrahimovic's frustration spilled over after a match with Villarreal. "I screamed out at Guardiola, I was screaming that he had no balls and that it was ridiculous that he did not talk to his player. I kicked over a box in front of him and sent things onto the floor.

"My idea was to get angry so that maybe he would talk to me. But nothing. He picked up the box, put it back and then walked out of the room."

Everywhere else he has played, Ibrahimovic has been regarded as a hero. In two of the five countries he has played, verbs inspired by him have officially entered the language. In France, the word 'zlataner' now officially means "to crush". In December, the Swedish Language Council registered the verb 'to zlatan', meaning to do something audacious or outrageously brilliant. He is more than just a footballer, he is a word, a way of behaving, a way of life.

What goes through his head when he is at the top of his game? "It goes quick, the thinking goes quick," he says. He pauses as he attempts to explain the inner workings of his mind. "I see pictures of what could happen in two or three steps ahead and I choose one. It is the way I play."

Ibrahimovic celebrates after scoring his miraculous fourth goal against England last November

He still plays with anger pulsing through his veins, but now it is channelled. "First the anger controlled me. Now I control it," he says. There was anger when he took to the field for a friendly against England in Stockholm last November - anger at the British media who questioned why he had never fulfilled his potential against English sides.

"I scored one, two and then three," he says, but it was his fourth goal that left mouths agape across the world, as he jumped high into the night air to bicycle-kick a clearance from England goalkeeper Joe Hart into the net from fully 30 yards - a goal that is regarded among the best ever scored.

Was it the best goal of his career? "I think so. It is a goal you don't repeat often. It is nice when you do something like that and it comes off."

It was a goal borne of the barefoot brilliance he developed as a child in Rosengard. "It is the way I always wanted to play," he says. "Why be like everybody else, when you can do something special, different?"

In the hallway of his Malmo mansion, a photograph hangs on a red feature wall. It is not in keeping with the lavish surroundings, it is of two dirty feet - "the feet that have paid for all of this."

They are the feet that took Ibrahimovic from the depths of a Swedish ghetto to the top of the world.

Listen to the full interview with Ibrahimovic in an hour-long programme on 5 live from 2030 BST on Wednesday.

- Published11 September 2013

- Published20 May 2013

- Published15 November 2012

- Published15 November 2012

- Published14 June 2012

- Published7 June 2019