Ilombe Mboyo: Prison, stardom and a terrible past

- Published

- comments

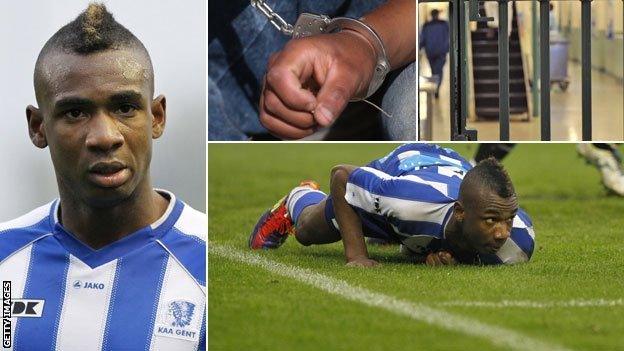

Ilombe Mboyo was nearly a West Ham player until fans found out about his rape conviction and voiced their outrage on Twitter. But can football help rehabilitate a criminal?

Pierre Bodenghien immediately knew he'd spotted a gem.

"He had everything - size, technique and physicality," remembers the 58-year-old scout. "He was equally good with his left and right foot and very versatile."

Bodenghien was watching Ilombe Mboyo play in an unusual setting - the Ittre jail, external in Brussels - and the training session was being held as part of the pioneering 'Football in Prison' scheme he was running, which had been started in 1995 by Princess Paola [now Queen Paola] of Belgium.

At the time, Mboyo's emergence seemed to be the crowning glory of the scheme.

The teenager was born in DR Congo and raised in Brussels, where he played football in the city's parks. One of the youths he played alongside in the parks was Vincent Kompany, now the captain of Manchester City and Belgium, who described Mboyo as a "rare pearl".

Having been a scout for more than 20 years, Bodenghien immediately recognised Mboyo's talent when he saw him playing at Ittre jail and alerted his employers at Charleroi., external Taking into account Mboyo's good behaviour in prison, an arrangement was then made with the judicial authorities for him to start training with the club.

Charleroi were managed by former Scotland midfielder John Collins at the time and he remembers: "[Mboyo] joined in with a couple of training sessions, with lots of passing and possession drills, and we then invited him to some trial games.

"At the time he still had to go back to prison once or twice a week. We talked about discipline and respect and working in a group.

"He was very quiet, as you'd expect from someone coming from prison and joining a professional group. He had the technical ability and was a strong boy - you could see he'd obviously been working out a lot in prison.

Mboyo signed for Belgian side Genk for £3.5m in August after a move to West Ham fell through

"But his behaviour was excellent. He just got on with his work and it was nice to see him adapt and integrate with the others. Everyone deserves a second chance."

After impressing in these trial games and again when he came off the bench for the reserves, Mboyo was signed by Charleroi in 2009 in a deal sanctioned by the Belgian courts.

His football career maintained a steep upward trajectory after that. He signed for Belgian Pro League side Kortrijk, external on a permanent deal in September 2010 and the following January joined Gent,, external where he really made a name for himself, scoring 37 goals in 80 appearances and gained the nickname "Le Petit Pele". He was even given the captain's armband.

Mboyo won two caps for Belgium during their 2014 World Cup qualifying campaign and could join the likes of Christian Benteke, Marouane Fellaini, Dries Mertens, Eden Hazard and Vincent Kompany on the plane to Brazil next year.

But this is where Mboyo's fairytale story suddenly takes on a darker hue. People began to look into the background of the star striker and it did not take long to find out he had been in prison after taking part in the gang rape of a 14-year-old girl in 2004, when he was 17 and a member of one of the most notorious street gangs in the Matonge district of Brussels.

The crime led to a seven-year prison sentence. Unsurprisingly, there was an outcry that someone who had committed such a serious crime should now be gaining fame and fortune as a professional footballer.

Mboyo insisted prison had changed him. "It was there, for the first time, that I realised the seriousness of what I had done," he said. "I decided to take responsibility."

The Belgian FA publicly supported the player when he was called up to the national team last year. Its president, Francois De Keersmaeker, declared: "Once someone's time in the cells ends, they don't necessarily have to be lost to society.

"It's too easy to stigmatise. Mboyo could be an example for young people who go down the wrong path."

Yet the view was not shared by everyone. Mboyo was on the brink of a move to West Ham this summer, before Hammers fans found out about his past and launched a Twitter campaign opposing the signing.

West Ham owner David Sullivan pulled out of the deal,, external explaining: "I couldn't go against the supporters. We wanted their opinions and they seem to have said no."

The player ended up joining Genk,, external one of the biggest clubs in Belgian football, for £3.5m instead.

While Mboyo has continued to progress in his career - he has three goals in seven domestic and European games for Genk this season - the controversy appeared to trigger the demise of Bodenghien's 'Football in Prisons' project, to which he had dedicated two decades of his life.

"Twice a week, 30 prisoners would come in for a training session, and far more wanted to participate," says Bodenghien. "It was very structured, with proper equipment and coaches.

"Prisoners learnt values such as self-discipline and how to be part of a team. If they misbehaved in jail, as a punishment they were not allowed to come to the sessions."

Mboyo says prison changed him and he realised the gravity of his crime while locked up

Enzo Scifo,, external perhaps the greatest Belgian footballer of all time, was even involved.

"Enzo would speak to the prisoners, which was a huge event for them as he was their idol," says Bodenghien. "The first time he came he was a little bit afraid because of the atmosphere - all the shouting and the noise of the keys and the doors slamming - but he was great with the prisoners."

The safety of Bodenghien and his coaches had been guaranteed by the powerful gang bosses inside the jails who would watch from the sidelines "managing" their teams.

"In 18 years I witnessed just one fight, even though the five-a-side matches were fiercely competitive - the team that scored first stayed on until they were beaten," the 58-year-old adds.

In fact, such was the scheme's success at Ittre, that it had been expanded to 12 other prisons across the country. And in a unique experiment, Bodenghien even brought a football team of prosecution and defence lawyers into the prisons, some of whom would have actively contributed to the incarceration of those they were playing against.

But in the wake of the Mboyo controversy the plug was pulled on the scheme's annual funding. Financial cuts were cited as the reason, although the scheme cost a relatively modest 15,000 euros a year to run.

Bodenghien attempted to carry on his work independently but found the Mboyo revelations had undone goodwill in the prisons.

"A lot of the guards were jealous [of Mboyo's success] because they didn't think an ex-prisoner has the right to earn a lot of money and popularity," he claims.

Disillusioned, he stopped bringing football to the prisons.

While Mboyo's case opens a wider - and highly emotive - debate about the social reintegration of those who have committed very serious crimes, Bodenghien can think only about the opportunities he feels have been lost with the closure of 'Football in Prison'.

"When inmates play football, they don't fight, they don't use drugs and a sense of teamwork based on respect for others can be built," he argues.

"It was something that I was involved in from the start and that was in accordance with my own personal values. It was a formidable human project."

- Published13 November 2012