Brazil, Russia and Qatar World Cups pose problems for Fifa

- Published

- comments

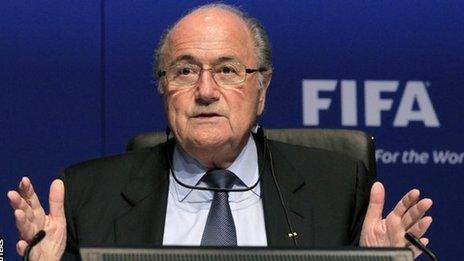

Sepp Blatter

It is almost three years now since Fifa awarded the 2018 and 2022 World Cups to Russia and Qatar respectively.

In that time, world football's governing body has had to withstand numerous allegations of corruption surrounding the joint vote that decided the hosts of both tournaments.

To add to the discontent, there has also been a purge of Fifa's executive committee, with eight members either suspended or forced to resign following claims of misconduct.

Fifa president Sepp Blatter,, external in England for the Football Association's 150th anniversary gala dinner on Saturday, will tell you that his beleaguered organisation is moving in the right direction.

Or, to borrow one of his favourite analogies, he is steering the ship towards calmer seas.

But, in many ways, the waters ahead look even choppier.

By choosing Russia and Qatar to follow next year's World Cup in Brazil, Fifa has guaranteed itself another decade of problems and negative headlines.

Fifa sources will tell you privately that for all the bad publicity around the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, there are far more concerns within the governing body about the tournament in Brazil.

Never mind the street protests and social unrest, which are almost certain to be an issue next year, there are still question marks over transport, organisation and infrastructure in the South American country.

Former England coach Fabio Capello, now in charge of the Russia national team, told reporters recently that he was worried about Brazil's creaking transport system and the demands of playing games in different parts of such a vast country, where temperatures and conditions vary greatly.

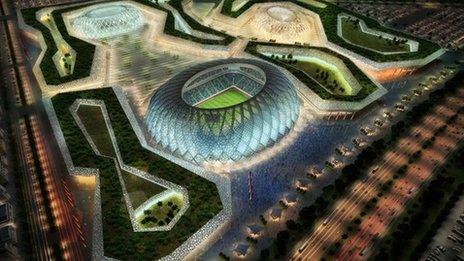

That is not to say that Qatar is without its own problems.

Fifa may have parked any decision on moving the 2022 World Cup from the stifling heat of a Qatari summer to the cooler temperatures of spring or winter, but the Gulf state's treatment of migrant workers following a Guardian investigation alleging slave labour is still to be addressed.

No doubt that topic will be on the agenda next month, when Blatter heads a Fifa delegation that will meet Qatar's new ruler, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani.

Fifa have parked any decision on moving the 2022 World Cup from the stifling heat of a Qatari summer to the cooler temperatures of spring or winter

As for Russia, it has received relatively little attention so far.

All that has changed after Yaya Toure raised the possibility of a boycott of the 2018 World Cup after claiming he was racially abused during Manchester City's Champions League game against CSKA Moscow this week.

While such incidents are sadly not new, it is the first time this issue has been so prominently linked to the World Cup.

The 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi are already facing the prospect of widespread protests aimed at Russia's new anti-gay legislation.

But racism and attitudes towards homosexuality in Russia are just two examples of a deeper concern in the west about Vladimir Putin's government.

Once the Sochi Games are out the way, Russia will find itself under even greater international scrutiny in the run-up to the 2018 World Cup.

As emerging economies like China and Brazil become more and more powerful, so sports bodies have been trying to use their premium events to break into new territories and markets.

Brazil, Russia and Qatar reflect that ambitious shift. But, by choosing these countries as hosts for the World Cup, Fifa has ensured it will be fighting major battles on three fronts.

- Published25 October 2013

- Published16 October 2013

- Published3 October 2013

- Published26 September 2013

- Published16 September 2013

- Published23 April 2013

- Published2 April 2012

- Published7 June 2019