Major League Soccer: Can the MLS revolution survive and thrive?

- Published

A lot has changed for "soccer" in the US since Steve Nicol arrived nearly 15 years ago.

"When I first got here I couldn't find the football scores in the papers. Now you can watch live games from any league you want," says the former Liverpool and Scotland star, who went west in 1999 to take a player-coach role at the A-League's Boston Bulldogs., external

The league and Bulldogs are no more - going the way of so many American soccer experiments before them - but Nicol stayed, moving to Major League Soccer's (MLS) New England Revolution, where he spent 10 seasons, external at the heart of something close to a football revolution.

MLS is currently coming to the end of its 18th season, which makes it the longest running professional football league in US history, beating the old North American Soccer League's (NASL) 17-season run from 1968 to 1984.

An average of nearly 18,600 fans have attended this season's games, putting MLS third behind the National Football League and Major League Baseball in terms of gates in US professional sport, and comfortably in the world's top 10 football leagues.

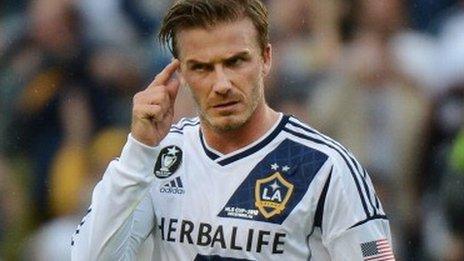

It is also growing. Having had only 10 teams as recently as 2004, 19 teams, three of them in Canada, played this season. A 20th, the Manchester City-backed New York City, joins in 2015, with four more "franchises" by 2020 - David Beckham's Miami "Nice" being perhaps the most eagerly anticipated.

MLS teams have also built or renovated 10 stadiums since 2005, and with many of them initially being unhappy tenants in venues designed for other sports, most now play in "soccer-specific" venues that have helped boost fan-bases and finances.

This has brought a more confident outlook. The league that nervously ripped up its rule book and threw money at Beckham in 2007, external (and tolerated a fairly modest return on investment in purely football terms), has shown its new ambition by bringing in the likes of Tim Cahill,Thierry Henry, external and, most recently, Clint Dempsey.

So is it time for us snooty, Old World-types to put aside our Ted Lasso stereotypes and start taking the MLS more seriously?

"Our goal is to be among the world's top leagues by 2022," says MLS's senior spokesman Dan Courtemanche.

That target will be measured on four criteria: the quality of play on the field, the passion of the fans, the relevance of MLS clubs in their "home markets" and overall financial viability.

"We have a group of owners who have been successful in business and their goal is to be profitable - look at the Bundesliga, that's our vision," adds Courtemanche.

Nigel Reo-Coker loving life in MLS with Vancouver Whitecaps

If World Soccer is to be believed, MLS is almost there. Earlier this year, the London-based magazine ranked America's top flight as the seventh best league in the world.

The Bundesliga and Premier League were first and second, but MLS, buoyed by high marks for competitive balance, crowds and venues, was just behind Mexico's Liga MX, and ahead of the Dutch, French and Russian leagues. Where MLS did not score so well, however, was on the actual football.

"They have done everything in terms of getting the league going - they've built it almost from scratch," says Nicol, who took the New England Revolution to four MLS Cups, the pinnacle of the US season, but lost all four.

"But what they have to do now is improve the product. That means bringing in better players, or producing more of their own."

Nicol says MLS clubs are trying to do both, but worries that the league's growth has diluted the quality.

"Seven or eight years ago I thought the best teams could have scrapped it out in the Premier League, but now they are more like Championship teams, top six perhaps," he says.

Los Angeles Galaxy have a wage bill of £6m, but a third of that goes to imported striker Robbie Keane

"There are just too many teams for the number of good players they've got. Take this move to 24 teams. Forget the squads, just look at the first teams: that's nearly 270 players. That will mean a lot of players having careers they shouldn't have."

Nicol's theory would seem to be borne out by MLS results in the Concacaf Champions League,, external the competition for the best teams in North and Central America and the Caribbean. Only two MLS teams have won it, and that was when it was easier to win as a knock-out tournament. Since the LA Galaxy's victory in 2000, Real Salt Lake's runner-up prize in 2011, external is the closest they have come. Mexican teams dominate.

But the real reason for this failure to kick on as a league in terms of quality is more complicated than a simple labour supply problem. There are 350 million Americans and Canadians, they are two of the richest groups of people to have ever walked the planet and, as Nicol points out, a lack of athletic ability is not the issue: MLS has the means to compete if only it would untie the arm it has behind its back.

To understand why this is the case you need to go back to the beginning.

Tim Cahill enjoying life at MLS club New York Red Bulls

Part of the legacy plan for the 1994 World Cup, MLS was founded with one guiding principle: don't fail.

Fond memories of Pele's New York Cosmos packing them into Giants Stadium in the 1970s had been replaced by recriminations at what went wrong after Pele retired, and regrets at lost generations of US talent that had no domestic league to aspire to or grow up in.

Like generals scarred by their last campaign, America's soccer chiefs tried to fight that war again with a safety-first approach aimed at winning over the domestic sports fan. This meant a salary cap, a franchise system that sees the league effectively own all the clubs and players, and a summer schedule to avoid American football, basketball and ice hockey.

If they were the measures meant to protect MLS from overreaching itself, the concessions to American tastes included a closed league, a college draft, play-offs and a dislike of draws - so no promotion or relegation, then, a regular-season of diminished importance and the gimmicky use of ice hockey-style shoot-outs.

The shoot-outs were soon abandoned, and the play-offs have been tweaked, but in all other ways MLS remains unlike other professional football leagues. This difference has helped see it through huge initial losses, and become the burgeoning success story it is today. But it is also holding it back now.

Let us take the salary cap of $2.95m (£1.83m), a wage bill comparable to a team in England's third tier. There are, however, caveats to note, the foremost being the Designated Player rule, better known as the Beckham rule.

This is the amendment that allowed teams to sign superstars that do not count towards the limit. Beckham was the first, but teams can now bring in three designated players.

David Beckham talks about why he chose Miami

This means a leading team such as the Los Angeles Galaxy have a wage bill closer to £6m - more like a Championship team - but two thirds of that is going to two players: Landon Donovan and Robbie Keane.

MLS, like other leagues in the US, has a collective bargaining agreement with its players, and this stipulates a minimum wage of $35,215 (£21,834), which is £5,000 less than the average annual salary in the UK, and £10,000 less than the Premier League's average weekly wage. One in 10 MLS players gets this salary, and four in 10 earn about £30,000 a year.

Some might say that is plenty for doing something that lots of us do for the sheer fun of it, but that rather misses the point of professional sport, and will not help MLS's global ambitions.

US journalist David Peisner spelled out the problem in a recent piece for Buzzfeed, external that asked where are the "middle-class" pros that every league needs. He explained that the constraints of the cap have led many players to take better-paid jobs in second-tier leagues in Europe. He also said it has created a dysfunctional team dynamic.

Peisner focuses on Kofi Opare, a minimum-wage player just breaking into the Galaxy's first team.

Explaining what it is like to train with players earning 100 times more than he does, Opare says: "Before you go in for a tackle (with Donovan or Keane), you're thinking, 'he's worth millions, let me get the other guy, the trialist'.

Beckham signs off in LA with MLS Cup win

"That's the way all the players feel. They're very cautious during practice. When Robbie Keane gets the ball, no one touches him."

This matters off the field, too. If there is one area MLS has not addressed it is its TV ratings - they are stubbornly poor.

Regular-season games this year have drawn tiny audiences by US standards, and even Beckham's farewell in last season's MLS Cup was beaten by a tape-delayed broadcast of Chelsea against Liverpool on the same day.

There are various theories for this, but the most obvious is that the US public is used to its leagues being the best in the world: they might not be as steeped in football culture as European or South American fans, but a US audience knows the real thing when it sees it.

The current collective bargaining agreement expires at the end of next season, and it is almost inconceivable that the league will not raise the salary cap and/or tweak the Designated Player rule. A move to a winter league so it better fits the global football calendar is also a possibility.

But it is also unlikely that the financial shackles will be completely cast off. As Courtemanche makes clear, the league is still establishing itself, and the nation's demographics are on its side.

A recent poll of young Americans for the broadcaster ESPN found that football was second only to the NFL in popularity. Among young Hispanic Americans it was number one, and there are now almost as many Hispanic Americans as there are people in the UK.

This is why Beckham is on to something when he says: "I think there's going to be a stage when football will explode and become one of the sports that will challenge basketball, baseball and American football."

He is on even safer ground in Miami, a metropolitan area of more than five million people, two million of whom are Hispanic.

Steven Powell, an executive at the Houston Dynamo,, external believes Beckham's return as a team owner could not be better timed.

"I'm not sure we have a vision of ever being bigger than the NFL," says Powell.

"But I certainly feel that some of the other US leagues that are perceived to be bigger or better draws than us because they're much older are within our sights in the future."

Nicol is still confident about the league's long-term future, too.

"Now that the NFL and college (American) football is on, it's hard for MLS - it's like going up against the Queen's Speech at Christmas," says the 51-year-old, who now works as a pundit for ESPN.

"But when I got here they couldn't give MLS teams away, now they're going for $100m. So it's getting there."

One of the most popular football podcasts in the US, external is run by two New York-based Brits who call themselves "Men in Blazers". The blurb on their website describes soccer "as America's sport of the future - as it has been since 1972."

It is a good joke, and reminiscent of descriptions of US sports in this country over the years, but it could also be true.

- Published30 October 2013

- Published30 October 2013

- Published4 August 2013

- Published18 May 2013

- Published21 November 2012

- Published7 June 2019