Monopoly money: Football's TV war makes the rich unreachable

- Published

A lot can change in sport in 10 years. That is why we keep watching: we do not know what is going to happen, but we know nothing lasts forever.

Well, that was the general idea for most of professional sport's history. Can we still say the same about football?

Much has been said and written about the game-changing potential of BT's £900m annexation of European club football from a broadcasting point of view. That much money for that many games represents the boldest and most sustained challenge to Sky's hegemony for 20 years.

There has been little comment, however, on the game-freezing implications of the deal from a football perspective. That is hardly surprising - it is not a story Uefa wants to acknowledge.

With Premier League clubs already enjoying the benefits of their huge new domestic and global TV deals, the cash from BT's European gamble will start to flow into the accounts of England's leading clubs from 2015-16. Everybody is getting richer, but the gap between the rich and really rich will grow ever larger, every year.

Combine that with the restrictions imposed by Uefa's Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules - and the corresponding cost controls brought in domestically - and you have the ingredients for the perfect preservation of football's pecking order.

"The fundamental effect of the BT deal will be additional wealth for England's big three - Manchester City, Chelsea and Manchester United - and probably the next three too, Arsenal, Liverpool and Spurs," says Liverpool's former managing director Christian Purslow., external

"You will now have six teams playing for four Champions League places, with the other 14 teams playing for survival. Never again will the likes of Everton, Newcastle or Villa get near the top - the difference in revenues will just be too great."

Jonathan Hill, the chief operating officer of the sports rights agency Kentaro,, external agrees with Purslow, and sees this ossification of the competition stretching beyond national borders.

"It will be the same teams, bar four or five, qualifying for the knockout stages of the Champions League too. Nothing will change," says Hill, a former commercial director at the Football Association.

The former Chelsea, Derby County, Everton and Leeds United chief executive Trevor Birch sees it the same way, although he thinks we should be grateful our elite mini-league is as many as six strong.

"In terms of revenues, that is what we are talking about," says Birch, who is now a partner at the business restructuring firm BDO., external

"But no other country gets close to that level of parity right now. Spain is dominated by two clubs, and Bayern are streets ahead in Germany.

"The relative strength of the competition in the Premier League is what continues to drive ratings around the world. It's what makes it such a compelling product. But that also makes things difficult for all the other leagues."

According to Deloitte's Annual Review of Football Finance,, external average turnover in the Premier League in 2011-12 was £115m, almost six times the amount Championship clubs earn.

Some might say it was ever thus: the biggest clubs have always done well, and the best predictor of football success is the size of your wage bill.

But are we entering an era where the biggest clubs never change?

In the 21 years of Premier League football, Blackburn Rovers are the only team currently outside the financial elite to have won it, and they were in the money then. Arsenal, Chelsea, Manchester City and Manchester United have shared the other titles.

In the 21 years of Division One football preceding 1992, seven teams won the league, including Derby County, Leeds United and Nottingham Forest. In the 21 years before that, 11 teams won the title, with Burnley, Ipswich Town, Spurs and Wolves all finishing first.

Eleven, seven, five - English football's list of potential champions is shrinking. It is a similar story in Europe.

For two glorious years, Jose Mourinho's Porto were almost unbeatable, at home and abroad, but when richer rivals came calling the club's owners could not afford to say no

Uefa acknowledges that there is a "close link between sporting success and financial buying power" but denies that its TV deals and Financial Fair Play initiative will make football less competitive.

"It is not true that it is practically impossible for clubs outside the elite to compete," a Uefa statement said.

"This season SV Zulte Waregem, Real Sociedad and Grasshoppers, to name just a few, all qualified for the Champions League despite being in the bottom half of wage-payers in their league, and in previous years the likes of SC Braga, Borussia Dortmund and FC Basel have punched above their weight at elite European competition."

Dortmund, however, are scarcely hard-up. They have the 11th highest turnover in Europe, and the issue is not occasionally being able to punch above one's weight - it is whether these teams can land knock-out blows.

Ten seasons ago, Jose Mourinho's Porto beat Monaco 3-0 , externalto win the Champions League. That victory represents the last time a team outside Europe's financial elite won the competition, and just like the only other relative minnow to achieve that feat in the past 20 years - Ajax in 1995 - the side was immediately disbanded,, external picked apart by richer rivals.

Mourinho went to Chelsea, taking Ricardo Carvalho and Paulo Ferreira with him (they would eventually be joined by Jose Bosingwa, Deco and Maniche), and one year later the only Champions League winner still at the club was the goalkeeper Vitor Baia.

Another talented young coach, Andre Villas-Boas, would inspire Porto to Europa League success in 2011, but the stars of that team were soon sold on as well. Trapped in a small-market league, with limited global appeal, Porto are condemned to be a selling club.

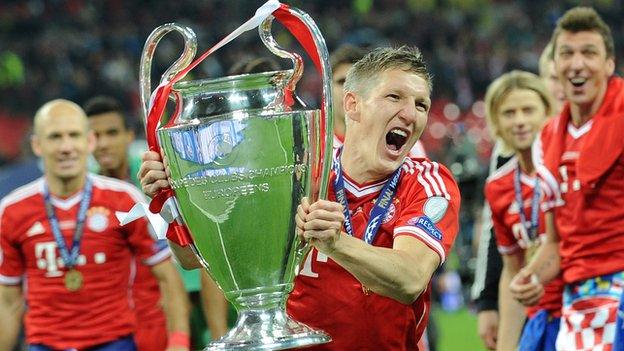

Compare their fortunes since that Champions League success with last year's winners Bayern Munich., external

Germany's "FC Hollywood" brought in £363m in the 2012-13 campaign, six times what Porto make, which is why Bayern can try to improve a treble-winning team with their chief domestic rival's best player, Mario Gotze, as opposed to cashing in on their own prize assets.

And Bayern will need to keep spending because their real peers - the likes of Barcelona, Real Madrid and Manchester United - have all posted record results of their own.

Last month, the Spanish juggernauts both announced that they made more than £400m last year, while United's results for the first quarter of their financial year suggest they too will get close to that figure.

In the understated language of a financial report, United's executive vice-chairman Ed Woodward , externalwelcomed the BT deal, saying it "represents a meaningful increase over the current arrangement, which should translate into higher broadcasting revenue for the participating clubs".

Too right it should. Deloitte's Austin Houlihan estimates England's four Champions League clubs can expect an extra £10m at least from 2015-16, and leading sports lawyer Daniel Geey believes a Premier League team that goes on to win the Champions League could earn as much as £75m from Uefa's prize money pot and "TV pool".

All this largesse is on top of the additional millions the BT- Sky battle for domestic rights has already brought Premier League clubs.

The worst team in the league this season will bank £60m in TV money, with the best claiming £95m. Manchester United's title-winning campaign last season was worth £61m.

Experts are already wondering what BT's European move means for the next time Premier League rights become available.

Sky can probably survive losing the Champions League, but nobody thinks BT will stop there. Media industry research firm Enders Analysis, external predicts "an inflationary bloodbath for all market participants".

That is just the domestic deal. The Premier League will earn £2.5bn from foreign broadcasters over the next three years, and that is without really breaking China and India.

"The BT deal means that Britain now spends about £44 per person on live sports rights," says Birch, who is currently the joint administrator at Scottish Premiership club Hearts.

"But in the world's two biggest countries it's about 2p per person. Football is the global game. It might take 20 years, but when football takes off there the growth will be exponential."

So if last year's Bayern versus Dortmund final at Wembley represented a slight diminishing of the Premier League's global status, this humbling will not last long.

Birch sees the competition for eyeballs in Britain and beyond as English club football's ticket back to the top - "the trend is in the Premier League's favour" - while Purslow is even more bullish.

"We have had a couple of seasons where people have been a bit down on the Premier League, but the BT deal shifts the balance back from Bayern, Barca and Real - it's that significant," says Purslow.

Kentaro's Hill puts it more succinctly: "The Premier League is back."

Even mediocre teams should notice an up-lift in their prospects.

"Mid-tier Premier League teams will have a stronger hand now than mid-tier teams elsewhere and that might enable them to compete more strongly at home, too," he says.

"Money isn't everything: you still need to build a good squad."

As long as Luis Suarez and Steven Gerrard keep performing, Liverpool have hope; but with Anfield holding them back financially, they cannot afford to miss out on Uefa's millions for much longer

That will cheer fans of Southampton and Everton, but the evidence of recent seasons suggests less wealthy teams can rarely sustain challenges for long: the market adjusts, good players move.

It was telling that the Professional Footballers' Association reacted to the BT deal by saying it wants clubs to use a minimum of three "homegrown" players in their starting XIs. The fear is that clubs will spend all this TV lolly on tried-and-tested talent, sourced from around the globe, as opposed to trusting their own academies.

This pressure will be most acute at clubs on the edge of qualification for European football. The battles for fourth place that we have witnessed in recent seasons are only going to get more frenetic.

With BT effectively doubling the amount of money in the English pot, Champions League qualification has never been more crucial, lucrative or self-perpetuating.

"If you miss out on Champions League football it just gets so much harder," says Purslow, whose old team Liverpool have not played in the Champions League since 2009-10.

"The difference between finishing fourth and fifth is profound. Americans would call it 'the cliff'. You miss out on £20-30m from Uefa, but it also affects match-day and commercial revenues.

"And the effect is cumulative and logarithmic - it gets more difficult each year.

"It's pure maths. If you finish fifth in the Financial Fair Play era you cannot close the revenue gap. Come fourth and you're fine. You can put £15m on the wage bill - that's three superstars."

Birch believes the gap for Liverpool - already hamstrung by their cramped and old-fashioned Anfield ground - could become "unbridgeable" if they fail to qualify for Europe this season. Spurs are another club who will find it increasingly difficult to compete without a new ground and Champions League revenues.

"I think people will be very bold in the January transfer market," is Purslow's prediction, and he is backed by Birch and Deloitte's Houlihan.

With two wealthy rivals using live football in a war for the UK broadband market, and clubs determined to keep their place inside the virtuous circle of Uefa's TV revenues, this is a very good time to be a decent footballer.

- Attribution

- Published11 November 2013

- Attribution

- Published9 November 2013

- Published9 November 2013

- Published7 June 2019