World Cup 2014: How Brazilian football has a language of its own

- Published

World Cup 2014: The best of Brazil's 'magnificent masters'

We are coming up to it; with the World Cup just a few days away we are getting close to a hora da onca beber agua. Or in English, the time that the jaguar drinks water.

This is colloquial Brazilian for the moment of truth, the decisive hour. The expression is ageing now, but when I first moved to Brazil 20 years ago the old guard of football writers would roll it out every time there was a big match.

Unaccustomed as I was (and still am, thankfully) to sharing water with dangerous large felines, it took me years to work out the meaning behind the expression; when the jaguar goes to drink, let's find out who else has the courage to quench their thirst.

There are still old timers in Brazilian football who refer to a defender as a 'beque' - a derivation of 'back.' Some, though their number is ever fewer, refer to a 'corner' rather than an 'escanteio.' Most of the words that show off the game's English origins have or are being phased out. But there is one word which remains absolutely crucial to an understanding of the Brazilian game - 'craque.'

'The word might have come from English, but the craque is the one who gives the game that distinctive Brazilian touch.'

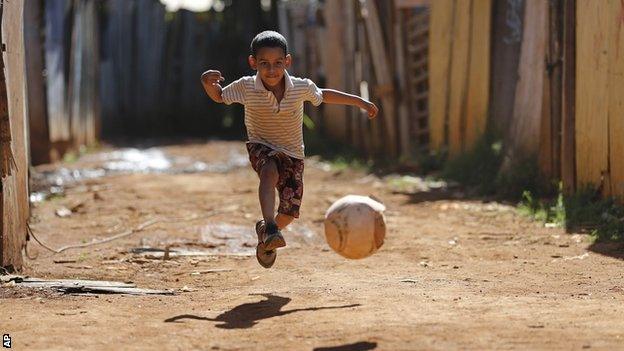

The craque is the star player, the man whose talent can tip the balance of the game in a micro-second. Neymar, for example, is undoubtedly a craque. The word comes from the English 'crack,' once used to describe the best soldiers. But it almost certainly crept into Brazilian football via horse racing (turfe), which was a major sport at the time that football was establishing itself.

The crack horse was the true thoroughbred. Incidentally, the land on which Rio's Maracana stadium originally staged horse races. I have lived in the city long enough to remember when the railway station alongside the stadium was still called 'Derby.'

The word might have come from English, but the craque is the one who gives the game that distinctive Brazilian touch. He dances round the opposing defender, showing him up as a perna de pau (wooden leg, expression often used for a bad player) with the huge defect of having a cintura dura (tough, or inflexible waist).

The craque will then unleash his 'chute' (you get no help with that one), where he will place the ball right there in the canto onde dorme a coruja (the corner where the owl sleeps) - as, for example, Ronaldinho did to David Seaman back in 2002.

The craque, though, can be over-indulged. He can start to get ideas above his station, and in a society as obsessed with hierarchy as Brazil, this can bring him back down to earth with a bump.

He is accused of being 'mascarado' - of having a mask on, to cover up his essential falseness and the fact that he is getting too big for his boots. Or shoes, because another sign of this excessive arrogance on the field is that he is tottering round on 'salto alto' - high heels, like some preening, self-obsessed vaudeville star.

If there is too much of this going on the crowd will soon get on the players' backs. The chant will go up, 'queremos raca' - we want race. This last word is a synonym for drive and commitment. Quite why this should be is unclear, for the word 'race' can hardly be applied to the Brazilian people, drawn as they are from European, African, Asian and indigenous origins.

Perhaps radio is to blame. Football became a national phenomenon in Brazil in no small part because radio carried it all across this giant land. Radio made football glamorous and exciting to a Brazilian audience, and gave it much of its language. Many of these expressions were first coined by creative radio reporters.

'An early elimination for coach Luiz Felipe Scolari's team, and 'o bicho vai pegar' - literally, the animal is going to take.'

It is unfortunate that the one they are best known for all around the world is those prolonged yells of 'goooooool.' This, though, has a practical explanation. It is much more than a mere demonstration of passion.

In many of the traditional Brazilian stadiums the stands are a long way from the pitch, creating problems for the commentator. While he is yelling, it gives time for him or one of his team to identify the scorer - a typically crafty piece of Brazilian improvisation.

Of course, if Brazil's craques fail to score enough goooools in this World Cup, then things could get ugly. An early elimination for coach Luiz Felipe Scolari's team, and 'o bicho vai pegar' - literally, the animal is going to take.

Why this expression should be used to indicate that all hell will be let loose is not entirely clear, but then some things will always elude translation - just as the craque Neymar will hope to elude all of those wooden legs over the next few weeks.

World Cup 2014: Brazil's Neymar scores cheeky penalty

For the best of BBC Sport's in-depth content and analysis, go to our features and video page.

- Attribution

- Published10 June 2014

- Attribution

- Published4 June 2014

- Attribution

- Published1 June 2014