Sierra Leone: How Ebola outbreak cost Johnny McKinstry his job

- Published

Johnny McKinstry on Sierra Leone & Ebola

Johnny McKinstry is on the final leg of a remarkable journey.

It began when he left behind a glamorous Manhattan lifestyle for the wonder and wastelands of Sierra Leone five years ago. It will end when he walks through the front door of the family home in Lisburn, Belfast for Christmas, having lived through an incredible time in modern history.

Very few 29-year-olds have managed a national football team. None have done it while that country is being brought to its knees by Ebola. "I'm very sad, very emotional," he said.

"Saying goodbye to Sierra Leone was very emotional, very difficult. I don't keep my distance from things; I invest emotionally. The country has become part of me."

Having been an academy coach with the New York Red Bulls, McKinstry was appointed technical director of the Craig Bellamy academy in Sierra Leone at the age of 24.

By 27, he was manager of the national team. Within 18 months his squad were in the top 50 of the world rankings for the first time. "I've made a career of proving doubters wrong," he said.

"The country has become part of me"

Two months ago he was sacked by email, as the Ebola outbreak gathered momentum.

"We believed we had the chemistry, cohesion and spirit to achieve anything. But the Ebola outbreak changed everything. Circumstances meant that, in the end, it was an impossible job."

McKinstry stepped off a plane four hours before we met in a London hotel. He had not slept for the best part of two days.

The journey to Freetown Airport had to be made by boat to avoid some of the areas worst affected by Ebola. An early flight meant crossing the night before.

A night at an airport, one plane to Morocco, another to London followed by a medical check by customs officers is no ordinary preparation for an interview. But for a man who has spent much of the past six months living in lockdown, being among the bustle again is a welcome change.

His time in Sierra Leone has now come to an end. The memory of it will, however, live on.

"In the last month or so when I went into Freetown for supplies, I started to see more of the Ebola response teams, with the full yellow bio-hazard suits," he said. "You might see an ambulance driving past and even the driver would be in the full bio-hazard gear.

"When you see that it really does bring it home to you just how serious the situation is."

McKinstry quarantined the academy behind the gate and walls of a compound.

McKinstry was offered a way out, a safe passage home in July, but refused it. Many of the players in the academy were from affected areas, he felt he had a duty of care not to walk away and send the young footballers into danger.

Instead he quarantined the academy behind the gate and walls of the compound. "When the outbreak started a lot of people ran for cover," he said.

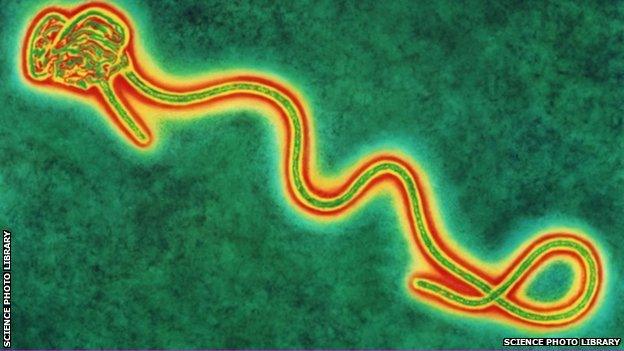

"But Ebola is a disease of contact, if you remove the contact, you remove the risk. So that is what we did. We moved everyone who was off site, behind the walls. We had generators for power, bore holes for fresh water, we had dorm rooms, classrooms and a football pitch."

In Northern Ireland his family were growing increasingly worried about the situation. Did they want him home? "They wanted information. They wanted to know what was going on, to know that I was safe, that the boys at the academy were safe," he said.

It is not sensationalist to suggest that the Ebola virus cost McKinstry his job as head coach. But before he explained how it came to an end, he addressed the question of how it all began.

"When it comes to football, confidence has not been something I have been lacking," McKinstry said with a smile. "There is a saying in Newcastle - 'shy bearns get nowt' - if you don't ask you don't get.

"That was my attitude to the Sierra Leone job. I know I was 27 but if they said no, nothing is lost. If they said yes, it was going to be the start of an exciting new chapter."

McKinstry had watched every Sierra Leone home game in person, every away game on TV, he had watched them train, studied their players. "I thought I was the best man for the job," he added. "I got in the room with the decision-makers and I went through Sierra Leone's last two games with a fine tooth comb and Tunisia's last two, who would be our next opponents.

"I outlined how I'd beat Tunisia, how I saw the future. Every member of the panel went away with a dossier, which I told them they could keep and use even if they didn't choose me.

"I outlined how I'd beat Tunisia, how I saw the future," McKinstry said of his job interview

"Two days later they offered me the job."

McKinstry made an impressive start, losing just one of his first six matches and leading Sierra Leone into the top 50 of Fifa's world rankings, above Northern Ireland, the Republic, Cameroon and Senegal. Then the Ebola outbreak happened and football became a side issue.

"We looked at what little we could do as sporting heroes, could we put smiles on the faces of the nation?" McKinstry said. "Football is a second religion in Sierra Leone.

"So when the national team wins, the national psyche is buoyed, everyone walks an inch or two taller. We made a commitment to keep on winning to try to qualify for the Africa Cup of Nations so that people in the country would feel a little bit better. Unfortunately it wasn't to work out that way."

The Confederation of African Football ruled that Sierra Leone could not play games at home. A challenging task was becoming a near-impossible one. "In football, the home team tends to win 50% of the time. In Africa, the home team wins 65 or 70% of the time," McKinstry explained.

That was not the only complication. "In my final game, against DR Congo, we had 17,000 fans just chanting 'Ebola, Ebola, Ebola' at us. It was upsetting for our players. The atmosphere was difficult. It made the players angry that people were mocking the situation in their homeland," he said.

Sierra Leone players found opponents unwilling to shake hands, hotels unwilling to check them in and governments uncertain on granting them entry. "People fear things they don't know," he said. "Hotel arrangements were monitored wherever we went, there were daily medical checks for my players and, while that is not overly difficult, it can impact on players' mental state."

Sierra Leone's first group game as they attempted to qualify for the African Cup of Nations was away to Ivory Coast in early September.

With a week to go, McKinstry was still unsure whether he and his players would be allowed into the country. The confusion meant some players had to buy their own plane tickets. Others arrived the night before the game.

Alhassan 'Crespo' Kamara chips the keeper against Tunisia

Sierra Leone led for an hour, only to lose 2-1. The demands of their schedule meant the squad left at 11pm that night to fly to DR Congo for a 'home' qualifier that was to be played in the away team's stadium. That game too ended in a 2-0 defeat and was marred by chants of 'Ebola, Ebola.'

McKinstry did not see the end coming. He said: "I had been in the FA building that day and not once was anything mentioned. I was driving back home, over a mountain pass, when my phone buzzed with an email from one of the men I'd been speaking to, not two hours earlier. It said they had terminated my contract., external I was disappointed. I'd been standing in their office a few hours earlier.

"But I believe in a certain way of doing things. So I spun the car around, went straight back to the FA, not to argue with them but just to go in shake hands and say 'best of luck for the future and it has been a pleasure for the past 18 months.'"

McKinstry has a voracious appetite for football and for learning, he lives and breathes it and his sense of adventure means predicting his next move is not easy.

In the New Year he has a series of meetings in Asia. This is not a man who does things by the book. Having been a coach from the age of 15, McKinstry already has miles on the clock.

The boyhood Newcastle United fan still dreams of taking charge at St James' Park or leading his native Northern Ireland out. "Nothing would make me prouder, my heart would be beating out of my chest for both those opportunities at some stage in my career."

Watch the full interview with Johnny McKinstry - Football Focus, BBC One on Saturday 20 December at 12:10 GMT.

- Published17 October 2014

- Published14 October 2014

- Published20 September 2014

- Published20 June 2016

- Published7 June 2019

- Published2 November 2018