World Cup leaves Brazil with bus depots and empty stadiums

- Published

The car park at the Mane Garrincha stadium in capital city Brasilia is now being used as a bus depot

Since exiting their own World Cup in unforgettably humiliating fashion, hammered 7-1 by eventual champions Germany, Brazil have recovered a degree of self-esteem with seven successive victories, most recently a 3-1 win over France on Thursday.

The team have a new coach and appear to have moved on, a process that will continue when they play Chile in London on Sunday.

But while Brazil have rebuilt on the field, another legacy of the World Cup remains a source of great discontent.

The Selecao have not played at home since last summer's tournament and the value of the physical infrastructure left behind by the World Cup remains bitterly contested.

With at least six of the 12 stadiums built for the tournament now in financial difficulty, local governments across Brazil are scrabbling to find productive uses for these costly state-of-the-art venues.

For Fifa, last year's World Cup was the most profitable in its history. Over the four-year cycle from 2011-2014, the event turned a £1.7bn profit.

For Brazil, the cost of building the stadiums alone was around £2.5bn,, external mainly from public money.

At a Fifa meeting in Zurich on 21 March, Jamil Chade, a Brazilian journalist, spoke to several senior officials off the record. In comments widely circulated in the Brazilian media, he reportedly asked one senior European delegate about the issue of the empty stadiums.

"That's Brazil's problem, not a footballing one," he replied.

From carnival to car park

Perhaps nowhere better illustrates the World Cup's problematic legacy than the Estadio Nacional Mane Garrincha in Brasilia, the country's capital.

Completed in time for the Confederations Cup in 2013 at a cost of £600m, the 72,000-seater stadium was the most expensive of all those built for the World Cup.

During the tournament it hosted seven matches, including Brazil's group-stage victory over Cameroon, as well as their ignominious swansong, a 3-0 defeat by the Netherlands in the third-place play-off.

Since that night, however, administrators have struggled to fill the venue. The stadium has cost the city over £1.3m since it opened.

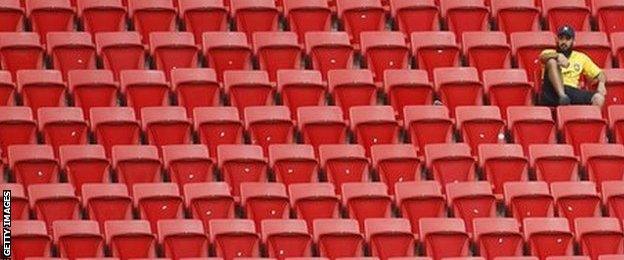

The 2014 World Cup brought a party atmosphere to Brasilia as fans breathed life into specially built stadia

But less than a year later those same arenas, such as the Estadio Nacional Mane Garrincha, are becoming money pits for the local areas

It is the only World Cup stadium yet to host an official football match in 2015.

So far this year, the only games it has held are two friendlies, part of the one-off Granada Cup tournament which brought together two top-flight Brazilian teams, Cruzeiro and Flamengo, two local teams, Gama and Goiás, Ukraine's Shaktar Donetsk and Lithuania's Zalgiris.

Part of the problem is the absence of any significant local clubs. Eight non-league teams from the Distrito Federal (DF), the administrative area around and including Brasilia, are currently vying for the single slot available in Brazil's Serie D, or Fourth Division. But with at best a few thousand fans attending home games, none of these teams have the support base to fill up a World Cup stadium.

Thiago Henrique, the press officer for Brasiliense, one of the larger local clubs, said the combined total attendance of all 80 games in last season's local championship would not have filled the Mane Garrincha.

"By hosting the World Cup here in Brasilia, the local clubs lost a stadium. We used to be able to play at the old Mane Garrincha stadium for free, now the running costs are just too expensive."

To run the stadium on match days costs £62,000. A local derby between Brasiliense and their biggest rivals, Gama, generates at best ticket sales of just £5,000, meaning that even with a good crowd, the two clubs would have to make up the £57,000 shortfall. For such small teams that is not financially viable.

Local team Brasiliense's total attendance figures would not have filled the 70,000-seater arena last season

Empty seats, empty wallets

Founded in 1960, Brasilia is a relatively new city, built from scratch by immigrants from other parts of the country. Many of the Brazilians who settled here retained their loyalty to the football clubs from their cities of origin.

Teams from Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo have much more numerous and devoted fan bases in Brasilia than any of the local sides.

Administrators had hoped that the presence of top-flight teams, drawn to a world-class venue and a passionate local following, would result in strong ticket sales. But not even Botafogo v Fluminense, arguably the biggest non-World Cup match of last year, managed to fill half the seats.

Brasilia is also in the midst of a serious financial crisis. When a new government took office in January this year, it discovered just £13,000 in reserves and monthly outgoings of over £400m.

As a result, the new government has been desperately trying to cut costs.

It cancelled Brasília's annual Carnival parade, for the first time since 1983, external, and now it has set its sights on reducing the stadium's maintenance fees.

According to Antonio Paulo, the DF's administrative management secretary, those fees run to £300,000 every month.

Signs of decay are beginning to show at the Mane Garrincha in Brazil's capital

Paulo, the city's administrative management secretary, said that while there were lots of reasons for Brasilia's financial problems, the Mane Garrincha was a significant factor.

"It's clear that the stadium was a major investment and it consumed a lot of the city's resources," he said.

Over the next month, around 400 civil servants from three local government departments will move into offices inside the stadium. According to local officials, the move will save the city some £2m a year in rent.

In the meantime, the city is also trying to save money by using the stadium car park as a bus depot.

Beyond Brasilia

Brazil's capital is not the only city struggling with the aftermath of the World Cup.

Manaus in the Amazonian rainforest, where England lost to Italy, also has a lack of decent local football teams. Average match attendance for the Amazonian state championship games this season was just 659. The Arena Amazonia was built to hold 44,000.

The stadium is expensive to maintain but it has had more success in attracting big crowds to friendly matches between Flamengo, Vasco and Sao Paulo.

Still, since the end of the World Cup, BBC Brasil estimates the stadium to have cost the city more than £560,000.

In Cuiaba, the Arena Pantanal was forced to close for "urgent" repair work in January. Local authorities admitted that just one year after its opening, the roof was leaking. A number of elevators and the air-conditioning system had also broken down. It has since reopened.

Relive all the goals from World Cup 2014

At the Fonte Nova in Salvador, north-east Brazil, the private company that runs the stadium, OAS, is now the subject of a major corruption investigation. A judge recently blocked its shares in the venue, leaving a question mark over who will administer the stadium in future.

In Natal, local team ABC FC have filed a lawsuit against the Arena das Dunas, the consortium that runs the World Cup stadium in the city. Under an agreement signed in 2013, matches between ABC and its local rival, America-RN are supposed to be played at the new stadium.

But disappointing match attendance figures for state championship games, with only one match attracting more than 10,000 spectators, has led to games being scheduled at the older, smaller Estadio Frasqueirao.

Even the Maracana, Rio de Janeiro's world-famous stadium, is currently running at a loss. To break even, it needs at least 30,000 paying fans per match. For this year's Rio state championship, average attendance was just 3,600, with the exception of Flamengo games, which attracted about 16,000.

While state championship games are not as popular as the Brasileirao, the main domestic league which starts in May, the auguries for next season are not good.

Empty seats are a common feature at Brazil's World Cup stadiums as low-profile fixtures fail to sell

Arguably, the biggest success stories in terms of World Cup stadiums were in the cities with strong local clubs, like Gremio in Porto Alegre, Cruzeiro in Belo Horizonte and Clube Atletico Paranaense in Curitiba. Even in those places, however, relatively high ticket prices and saturation TV coverage mean match attendance figures often disappoint.

"We knew this would happen," said Juca Kfouri, one of Brazil's most respected football columnists.

"I think it was the fault of the Brazilian authorities, not Fifa. Brazil accepted the conditions. There was no post-World Cup planning. I think this waste could have been avoided if we had tried to do a World Cup in the style of Brazil, and not in the style of Germany or Japan."

Brazil opted to build 12 World Cup stadiums, when Fifa regulations only required a minimum of eight.

Olympic revival?

According to Fifa's own accounts, the 2014 World Cup generated around £3.2bn in revenue for the organisation, compared with £1.5bn in expenses - a profit of £1.7bn.

In the income statement released earlier this year, Fifa noted that "revenue significantly increased compared to the previous four-year period [up to South Africa 2010] as a result of higher income from the sale of rights".

As for the longer-term sporting benefits for Brazil, Fifa points to a £67m grassroots development fund, external it has established in the country in the wake of the World Cup.

BBC's closing 2014 World Cup montage

But at its press conference in Zurich on 21 March, Fifa was adamant that 2014 was over. "We are not talking about Brazil," said Walter de Gregorio, the director of communications.

Despite the costs, and Brazil's calamitous performance against Germany, many Brazilians believe the tournament was a success. Some of the stadiums, including those in Brasilia and Manaus, will get a new lease of life when they host Olympic football matches in 2016., external And even Mr Kfouri argues the hosts did a great job charming their visitors.

But if previous World Cups are a guide, it will be a long time before Brazil's stadiums become self-financing. In South Africa, all bar one of the nine venues built or renovated for the 2010 tournament are in the red, unable to attract enough regular sporting contests or music concerts.

George Hilton, Brazil's new sports minister, defended the government's handling of the World Cup.

"The Mane Garrincha is a valuable stadium," he told the BBC. "Like the others we built, it is an important part of our national sporting legacy. These venues will be used for events other than football, and they will be important spaces for practising all kinds of sport in Brazil."

- Published25 March 2015

- Published26 March 2015

- Published8 July 2014

- Published20 June 2016

- Published7 June 2019

- Published2 November 2018