Women's World Cup 2015: The dilemma facing mums

- Published

Children are part of the team for the United States

A special note was slipped under the hotel room doors of Norway's players in the run-up to their Women's World Cup match against Thailand in Ottawa.

It was nothing to do with football; it was an invitation from midfielder Solveig Gulbrandsen's young son to his ninth birthday party.

The veteran midfielder's husband Espen, their son Theodor and three-year-old daughter Lilly were all staying in the team hotel and were very much part of the squad.

Solveig Gulbrandsen's family were in Canada for the first 10 days of the tournament

"We have followed this principle for many years and it works quite well," says Norway's director of women's football, Heidi Store, a 1995 World Cup winner.

"The children stay at the same hotel as the team and Solveig is able to spend some time with them every day. This increases her wellbeing and performance on the pitch, in our experience.

"The other players are used to having these children around and it does not affect them negatively - it is rather the opposite."

Gulbrandsen, 34, could add to her 183 caps when Norway face England in the last 16. However, her family will no longer be present by that point, having only stayed for the first 10 days of the tournament.

"It means everything to have had them here," she says. "It means that I can play; if you take the pre-camp and the whole length of the tournament, it's too long to be away. For me, it's important to have them around sometimes - not every day, but in a part of this long journey."

An issue that continues to trouble England

Norway's approach is in contrast to that of the English Football Association, which does not allow any family members to stay in the women's team hotel, citing the need for players to concentrate on their football.

It is the same for England's men, who had their fingers burnt at the 2006 World Cup when the decision to allow families to join the Three Lions in Germany backfired - the shopping sprees of the players' wives and girlfriends making bigger headlines than the football.

The presence of the wives and girlfriends of the England players at the 2006 men's World Cup caused controversy

The FA stance means one of the two mothers in the England team, veteran midfielder Katie Chapman, thought she would not be able to have her husband and three boys by her side in Canada, as the FA does not pay for families to travel.

Chapman, twice named FA International Player of the Year, only recently returned to England duty after a five-year hiatus that she says followed the cancellation of her contract when she asked for time off to be with her children.

Having been picked for England's World Cup squad, Chapman said the FA could still improve its childcare support and that she expected to endure a "really tough" time because she could not afford to pay to fly her family out to Canada.

In the end they arrived anyway, at their own expense, to surprise the Chelsea skipper for her 33rd birthday and her youngest son's second, and she has been able to see them during the downtime permitted to all players at head coach Mark Sampson's discretion.

Katie Chapman said her central contract was cancelled in 2010 when she asked for time off to be with her family

The FA says it is in the process of reviewing its childcare provisions and "benchmarking against other sports".

"Our players are supported financially through central contracts and we take a flexible approach to the terms of those contracts, factoring in various considerations including players' childcare commitments," the FA says.

However, Chapman's England colleague Casey Stoney, who has twins with her partner, the former Lincoln Ladies skipper Megan Harris, has had to remain in contact with her children through Skype.

And despite her delight at seeing Chapman unexpectedly reunited with her boys, Stoney says she felt a strong pull for her family afterwards.

"I was emotional because they'd done that and then straight away I thought 'oh, my children aren't here', and I had a bit of a wobble," says the 33-year-old, who was made an MBE on 13 June.

"But that's to be expected in tournament football. I'd love to have them here but I just financially can't do that. I miss them so much."

Different countries, different approaches

Many of the footballing mothers in this World Cup will be away from their children for long periods, but that is not to say Norway are alone in their enlightened approach.

Since 1996, US Soccer has allowed children into each training camp, paying for the cost of one nanny - usually a close friend or relative - plus their airfare and accommodation.

"It's an important element to help players with children to continue to contribute to the national team," explains US Soccer spokesman Neil Buethe.

"It allows players the ability to concentrate on their job of playing soccer without having to be away from kids for long periods of time, or worry about how they will be able to balance their family and career while on the road during a training camp."

The "soccer moms" in the US squad include defenders Shannon Boxx and Christie Rampone, striker Amy Rodriguez - and head coach Jill Ellis.

Children have never stayed with their mothers in the USA camp during major tournaments, but speaking to Fox Sports recently, 37-year-old Boxx praised US Soccer's policy of allowing them to be "part of the team" at training meet-ups.

She added: "It's so great to have my little daughter there knowing that there are 23 other moms there to take care of her at times."

Reigning world champions Japan have no mothers in their Canada 2015 squad but the Japan Football Association has previously paid for former midfielder Tomomi Miyamoto's son and her mother to attend her training camps.

Their current policy, put in place in 2008, allows players to bring children aged 18 months to three years, and a babysitter, to camps lasting no more than two months.

The JFA says it hopes this can bolster the national team by allowing players who are mothers to concentrate on their game while helping "enhance and activate women's football in Japan by showing hope and a reassuring picture of the future to female players".

As most nations at this edition of the World Cup have no mothers in their team and never have had, many say their approach to the issue will be considered when it becomes necessary.

Among those countries is Switzerland, whose spokesman says: "If one day we do have players who are mothers, we are very likely to cope with such a situation not according to some overall policy, but according to the best possible personal solution for both mother/child and the team."

'I really miss him a lot'

Madeleine Ngono Mani (right) scored twice in three group games

Cameroon striker Madeleine Ngono Mani says she does not get assistance from her association and it would be a "really big step forward" if a policy was introduced.

The 31-year-old has not seen her 13-month-old for almost a month and he remains at home with his dad in Cameroon.

"I really miss him a lot," she says. "If some people say they don't miss their children when they're away, well, it's not at all the case with me."

Cameroon have just made it through to the knockout stages so Mani will have to wait a little while yet before she meets up with her son again, but she is hopeful improvements in childcare will come.

"Even if I don't end up benefiting from something like that myself, I hope at least that some of the younger players do, one day," she says. "I'd really like that to happen."

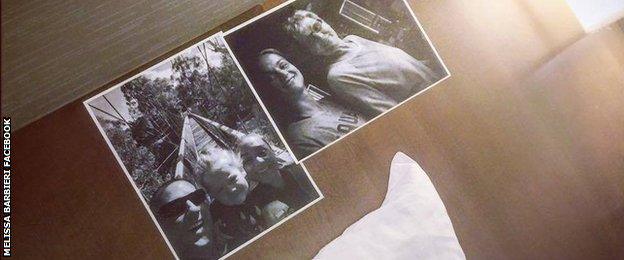

Australia's veteran goalkeeper Melissa Barbieri, who is taking part in her fourth World Cup, kept her husband and daughter close to her in spirit before the opening match against the USA by taping a photo of them to her locker.

"To remind me who is with me on this journey," she wrote after posting a photo of the image with another family picture on Facebook., external

Australia's Melissa Barbieri has been an active social media user during the World Cup

All told, there have been enough footballing mothers at this World Cup to make a team if you also include Sweden and Chelsea Ladies goalkeeper Hedvig Lindahl, who has a son, and Ecuador midfielder Erika Vasquez, whose daughter is two years old.

And while some of these players will remain in Canada for longer than others, they and their teams will have many reasons to feel pride in their achievements.

"I made a conscious decision that I was coming out here to make my children proud," says England's former skipper Stoney. "And that is what inspires me every day."

Casey Stoney (right) has twins with her partner Megan Harris

- Published18 June 2015

- Published18 June 2015

- Published18 June 2015