MLS at 20: How football in the USA is thriving at last

- Published

New York Red Bulls are one of the MLS sides prospering this season

Everybody works for the same company, you can never leave no matter how bad you are, you spend eight months deciding who wins only to play for two more months to decide somebody else has won and you do all this while every other player in the northern hemisphere is on the beach.

"It is the most intriguing, head-scratching league in world football," admitted Major League Soccer commissioner Don Garber when I pointed out that his league is a bit… well, different.

Garber, aka 'The Soccer Don', has run MLS since 1999, having left a good job at American football's NFL.

The head hunter involved on that one really earned their corn as the NFL was at that time the only football league the USA cared about, dominating the national conversation in a way our Premier League can still only dream about, and MLS was…different.

Rebooting the game in the US after the demise of the North American Soccer League (NASL) in 1984 was a condition of the successful bid to host the 1994 World Cup.

US Soccer won that beauty contest in 1988, and the fact MLS did not start until 1996 - long after the good vibes of the USA's decent showing in 1994 had worn off - should tell you that broadcasters, investors and sponsors were not climbing over each other to get a professional league up and running again.

Or perhaps they were just waiting for somebody else to do all the heavy lifting, so they could swan in and apply the finishing touches?

That is certainly one interpretation of a grim first five years for MLS: collective losses of $250m (£180m), teams rattling around gridiron stadiums far too big for them, gimmicky rule-changes that upset long-standing fans and a lacklustre product on the pitch.

MLS has come a long way since this game in its inaugural season in 1996

Nobody wanted to televise it, sponsors shied away, the best American players escaped to Europe and the rest of world football barely noticed.

But then - in lots of small, almost imperceptible ways - everything started to get better to the point where MLS can bring down the curtain on its 20th season on Sunday knowing it has never been more popular, relevant or secure.

"I think we get a bit more respect outside the US than we do from pundits here - I call them soccer snobs," laughed Garber.

"Our ratings are growing and it's our first year having global live match distribution, so we've got a lot of growth in front of us.

"I think people are intrigued by our structure, this unique system we have with salary caps, union agreements and strict revenue-sharing, this partnership among owners who are competitors on the field. That has created a lot of buzz and it's something for us to be excited about."

Garber is right, there is buzz and excitement, and the achievement of getting here, only 13 years after it looked like the league might fold, must be noted.

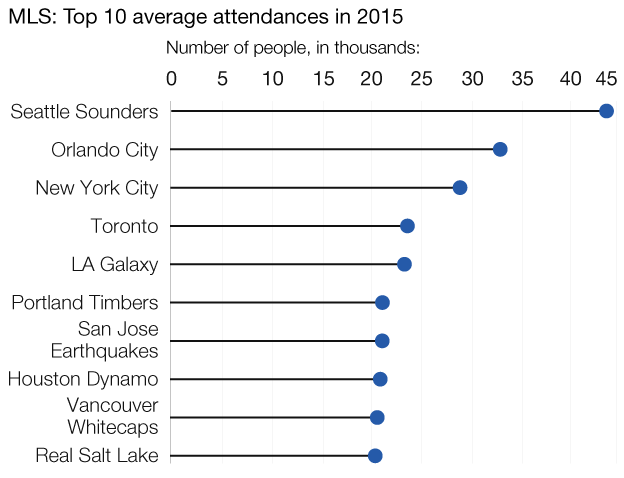

Seattle Sounders have sold out 126 straight games

But it also cannot be underestimated just how unusual MLS really is.

One, the league operates as a single entity. The team owners are actually "operator-investors" who run a franchise or six, as league co-founder Philip Anschutz was forced to do during the wobbly years.

Two, like every other sports league in the US, there is no promotion or relegation. The drop is bad for business.

Three, to emulate the thrills and spills of the race for fourth or relegation dogfight, the MLS Cup winners are the last team standing in the play-offs, not the best team over 34 regular-season games.

Four, the league has a salary cap to keep costs down and promote competitive balance, the latter helped by a draft system for the best college players and a "whose turn is it?" approach to signing more established stars and overseas talent.

Five, the salary cap (which should be a flagrant restraint of trade but is just one of the wonderful mysteries of American professional sport) is not really cap at all - it is more of a gentlemen's agreement to not spend too much, unless there is a player we really want.

David Beckham, external is the most famous example of the 'designated player' caveat and his arrival at LA Galaxy in 2007 on a salary of $6.5m (almost twice this season's official salary cap for each team) signalled the end of MLS' hair-shirt era and alerted agents around the globe that the North American market was open for business.

Big names have helped MLS get over teething problems and become a viable league with a growing international profile

It has also resulted in one of the world's most unequal societies. Beckham's successors Steven Gerrard and Robbie Keane account for 55% of the Galaxy's pay roll.

The average MLS wage - inflated by 50 or so designated players - is £187,000 but the median wage, the actual middle salary across almost 600 players, is £73,000. Gerrard earns £4.2m and Brazil's Kaka gets £4.7m at Orlando City.

I could carry on listing differences - it is a summer league, it spans two countries (17 teams in the US, three in Canada) and four time zones - but the point is simple: the MLS is different.

But is it any good?

"I think our clubs are as good as the [English] Championship teams but I don't know," said Garber.

"Years ago I said one of our MLS Cup winners, the Galaxy, could play in the Premier League and somebody slaughtered me on social media.

"At the end of the day that's irrelevant to us - we're not trying to compare ourselves to the Premier League.

"We're trying to have a league that could resonate enough in this country to be part of the conversation with the other major league sports but also earn the respect and commitment of soccer fans here."

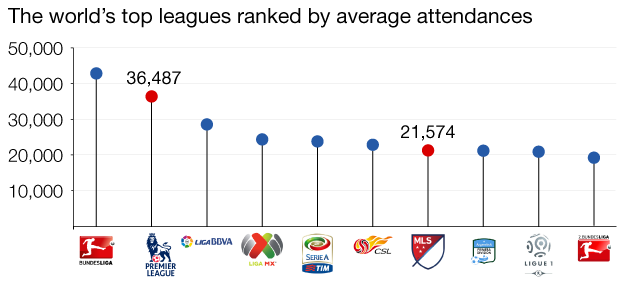

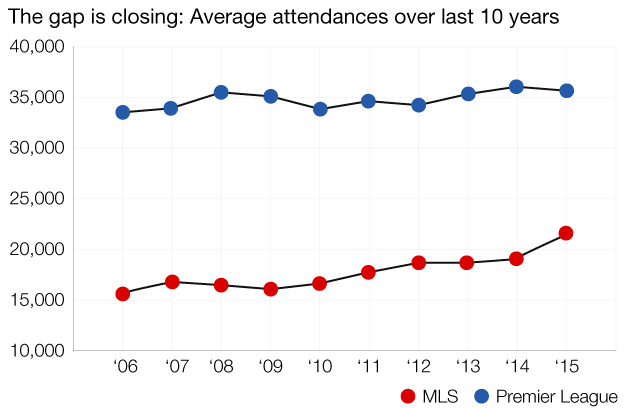

Again, Garber is right: comparisons with a much richer and more established league in a football-mad country are unfair, and his immediate targets should be the National Hockey League, National Basketball Association and Major League Baseball, which all earn much more TV and sponsorship revenue at home than MLS does.

But Garber cannot pretend these comparisons do not matter: the Premier League is booming in his backyard - TV ratings for English games dwarf those for his games - and the Bundesliga, La Liga et al are all eyeing the North American market.

So quality is important, particularly in a country where fans assume their domestic leagues are the best in the world.

Former American goalkeeper Brad Friedel was at the same New York conference as Garber and the former Premier League star caused a stir during a session on the future of MLS when he said the US did not have a player as good as his former Spurs teammate Mousa Dembele.

"Look, MLS isn't the Premier League or Bundesliga," Friedel, who won 82 international caps, told me.

"But I couldn't categorise it as Championship level because there are some clubs in the Championship and Premier League that would have a very difficult time over here.

"You've probably seen the quotes from Steven Gerrard recently. There are so many elements that go into it: travel, humidity, heat, altitude, freezing conditions.

"It's impossible to compare. In England, travel is short, the weather is pretty similar from north to south, give or take some rain, so it's difficult to compare."

Lampard: MLS is no retirement home

Having swapped the city of Stoke for Orlando, Phil Rawlins is another well qualified to assess the game on both sides of the Atlantic.

"It's a difficult question to answer but MLS is a very competitive league," said Rawlins, the co-founder and president of MLS' 20th team.

"I would say it's Championship level but with a difference. I think you see a passing game from most teams, Arsenal-esque in the way they go about the game.

"But it's very athletic and physical, so mid-to high-level Championship, if you had to put it somewhere."

Rawlins, whose marquee signing is Kaka, was not surprised to hear Gerrard say he was finding life in MLS harder than expected.

"It's the same thing with everybody who comes over," he said.

"Think about it: you're in Los Angeles and you go to play in Colorado, you're playing a mile above sea level. You go to Florida and it's 95% humidity and a six-hour flight.

"It's like playing in a European league, every week, and you're not in luxury jets.

"Factor in the time differences. When we go from east coast to west coast, the guys are waking up at four or five in the morning, because of their body clocks."

Gerrard's former England colleague Shaun Wright-Phillips, who joined his brother Bradley at New York Red Bulls this season, is even more succinct.

"It's a lot harder here than people think," said Wright-Phillips, whose Red Bulls were the best team in the regular season only to lose to Columbus Crew over two legs in the conference finals.

"It's easy for people [in England] to just watch it on TV and comment, instead of coming here and playing. They should try it to give me their feedback after that."

The fascinating thing about the relative struggles of Gerrard and the Galaxy, is that all the big-budget MLS teams disappointed this season compared with the teams that made the conference finals, the Crew, FC Dallas, Portland Timbers and Red Bulls.

Those four do not have huge disparities in pay in their squads and have all, like canny fantasy-football managers, looked for value in the middle bracket. That is a lesson for the entire league.

"I think the next step is to raise that middle class, that core player - that's where the emphasis has got to be," said Rawlins.

"It's about bringing up the quality around the star players we have and bringing in younger star players - the [Italian Sebastian] Giovincos and [Mexico's Giovani] Dos Santos of this world - we need more of them."

Giovinco was the league MVP this season and has earned a recall to the Italian squad

Friedel, who is now an MLS pundit for Fox Sports, agreed and said every team owner, sorry, operator-investor, knows the salary cap will have to be lifted.

"The idea is to have a very good core of players at each club and then, if you want to, sprinkle in a few DPs so there isn't going to be too much of a discrepancy in pay between them," said Friedel.

"There will be some discrepancy, there is in all American sports, but you can get very good players in that $250,000-400,000 salary range.

"That is on the agenda of every single league meeting and the owners know they need to do it.

"But you don't want to get into a situation where there might not be a league. They've had some tough times in the past but they've created a very stable environment now."

That is a point echoed by Garber, who is understandably reluctant to take off MLS's stabilisers just yet.

"We need to continue to grow our fan base and that does mean investing in the middle of the roster," said Garber.

"That's just about money and it could be solved overnight. But if we spent more money without growing our revenues, that's not a good model for anybody's business."

Slow and steady progress, then, seem to be the watchwords and it is hard to argue with that when you recall the wreckage of early 1980s NASL and what so nearly happened to MLS little more than a decade ago.

That will not please every football fan in North America, though, and MLS will have to live with the risk that it could always be overshadowed in its own market by the European leagues.

But Garber, Rawlins, Friedel and co are all building something substantial - and the fact it is so different might end up being its trump card.

- Published19 November 2015

- Published17 November 2015

- Published8 July 2015