Bosman ruling: 20 years on since ex-RFC Liege player's victory

- Published

What happened to Bosman the man?

A Cruyff turn, Fergie time, the Matthews final: football's icons have often entered the language of the sport but can any of those greats claim to have changed the game as much as the nervous, middle-aged Belgian sitting in front of me?

Jean-Marc Bosman did not trademark any moments of skill, score famous late winners or carry his teams to success but he was good enough to win 20 youth caps for Belgium and break into the first team of one of his country's best clubs at 18.

That, however, is not what earns him a place alongside Charlemagne, Audrey Hepburn and Hercule Poirot in a list of famous Belgians.

Twenty years ago on Tuesday, Bosman emerged from the European Court of Justice with a win that turned Europe's top divisions into glorious expressions of multiculturalism and added a new noun to sport's lexicon: the Bosman.

From that moment, players at the end of their contracts - David Beckham, Sol Campbell, Steve McManaman and many more - could move without a transfer fee.

No longer would a player from the European Union have their opportunities in the single market curtailed by rules limiting the number of foreigners clubs could field.

But for this softly spoken 51 year old, it was a case that almost ruined him.

The Bosman ruling explained |

|---|

1983: Youth international Jean-Marc Bosman joins Standard Liege |

1990: A move to RFC Liege fails to revive his career and his contract expires |

Dunkerque want to sign him but will not meet RFCL's fee, the Belgian club then cuts Bosman's pay by 75% |

Bosman's lawyers, including Jean-Louis Dupont, sue club, Belgian FA and Uefa for restraint of trade |

1995: EU court says out-of-contract players can move on free transfers, and bans limits on number of foreign EU players |

Sol Campbell and Steve McManaman among first to make lucrative free transfers and English clubs improve in Europe, but smaller clubs struggle to retain talent and wages rise |

2013: Bosman sent to prison for assault |

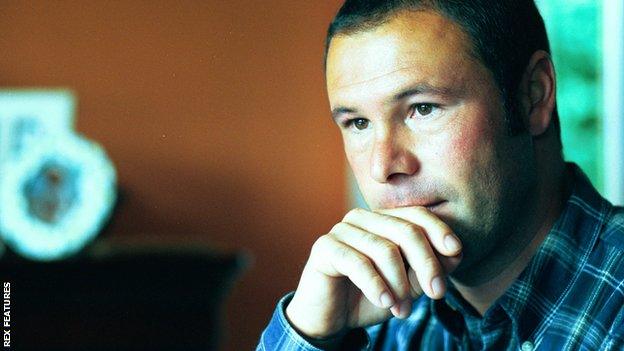

"There have been real problems but I am feeling much better now," said Bosman when I asked him how he was after a spell in prison, bankruptcy and a long battle with alcoholism.

"I've had medical and psychological care and I also have blood samples taken on a regular basis.

"There have been difficulties and my financial situation is not easy but life has started over. I have regained strength and feel motivated.

"It has not been easy to find work after the ruling but I am not complaining. The tunnel is nearing its end."

He entered that tunnel in 1990 when his contract with RFC Liege expired. With the club in financial trouble they wanted the midfielder to sign a new deal on a quarter of his former salary.

Yet when Dunkerque, across the border in France, wanted to buy him, Liege demanded four times what they'd paid for him in the first place.

"It was illogical," said Bosman, explaining the moment he decided to become a "freedom fighter".

His lawyer thought it would take two weeks. It took five years; a period that should have been the best years of a decent career.

Banned in Belgium, Bosman moved to a second division club in France, only for them to go bust. Other clubs told him they would like to sign him but could not because they already had three foreigners.

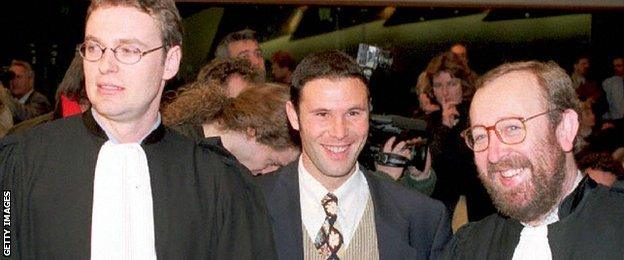

Bosman, with two of his lawyers Luc Misson (R) and Jean-Louis Dupont (L), smiles inside the European Court of Justice on 15 December 1995

He had a brief spell on the island of La Reunion and another go in the Belgian leagues, but it is an understatement to say his decision to take football's business model to court made him less attractive to club chairmen.

Broke, tired and out of shape, he accepted 350,000 Swiss francs in damages for his legal victory and began a life after football that he is still trying to work out.

There was a disastrous investment in a t-shirt business (he had hoped grateful footballers would buy one, only his lawyer's son did so) and problems with the taxman.

In 2011, he was convicted of assault following claims he had been involved in an argument with his girlfriend after he asked her daughter to get him some booze. Initially, the courts were lenient but when he failed to pay his fine they were left with little choice. He was sentenced to a year in prison in 2013.

It was then that Fifpro, the international trade union for footballers, stepped in. The stars he had helped become multi-millionaires may have forgotten him but his union did not.

"I was young and handsome then and I now have become old," he explained.

"Most of the players won't be able to recognise me but my case is still being talked about - I think that is positive.

Former Tottenham Hotspur captain Sol Campbell moved to Arsenal on a free transfer in 2001

"I may not be here in 20 years' time but they will still be talking about it and if someone remembers me I will give him my bank details. Everyone benefited from the Bosman ruling except me!"

I am speaking to him at Fifpro's swish headquarters in a suburb of Amsterdam. Bosman has become a spokesman for the organisation's campaign to finish what he started: scrap transfer fees entirely.

The best way to understand this is to view Bosman as a battle in a 125-year war between clubs and players.

The players won Bosman but were "ambushed", in the words of Fifpro's general secretary Theo van Seggelen, six years later. The European Commission made a deal with the game's governing bodies, Uefa and Fifa, to stem what the clubs claimed was rampant "player power".

This deal was enshrined in Fifa's Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players, external in 2001.

These rules set out today's transfer system - windows - the concept of a protected period when a contract cannot be broken, maximum and minimum contract lengths and so on - and for Fifpro they amount to the pendulum swinging towards the clubs.

Andy Webster's move from Hearts to Wigan Athletic threatened to be revolutionary in setting compensation players needed to pay for breaking contracts before the Court of Arbitration for Sport intervened

Five years later, a row about Scottish defender Andy Webster's move from Hearts to Wigan Athletic, external saw that pendulum swing back.

The details of the case are convoluted but the final ruling seemed to fix what compensation a player/new employer should pay the old employer for breaking a contract outside of the protected period. This sum would be the wages the player would earn if he stayed.

This really could have been revolutionary but two years later the Court of Arbitration for Sport changed the compensation equation by adding pro rata slices of the initial transfer fee and an estimate of the player's replacement cost.

Players such Andrea Pirlo or Robert Lewandowski could still let their contracts expire to get Bosman moves to new teams and bigger wages. But clubs wanting to sign players still under contract, even outside the protected period, would have to cough up some compensation, as Manchester City did with Raheem Sterling last summer.

Quite right too, is the usual response to this compromise between a player's right to ply his trade on the one hand, and a club's right to stability and a league's competitive integrity on the other.

Everton manager Roberto Martinez, the first Spanish player to get a Bosman to England, has criticised the transfer window, but does not want to scrap compensation.

"The Bosman ruling was a huge shock at the time but I used it and it now seems a normal way to move freely," said Martinez last week.

"Football has benefited from the multicultural input of players and it seems normal now.

"But it wouldn't be right to scrap transfer fees. The value of a footballer is important and the value of developing players is important."

"I was young and handsome then and I now have become old" - Jean-Marc Bosman

But Fifpro's Van Seggelen says this view is based on a misunderstanding of the players' position, as well as being unfounded in truth.

Dr Stefan Szymanski, author of the best-selling Soccernomics and professor of sports management at the University of Michigan, did some research for Fifpro earlier this year which outlined how the system was failing to do any of the things it promised in 2001.

According to Szymanski, the settlement has led to the rich clubs getting richer as more than half of all transfer spending circulates among them, with little trickling down the pyramid, far less than is syphoned off by agents.

He also outlined how the same clubs and leagues keep winning, while the same types of clubs and leagues keep failing, leaving themselves, he says, vulnerable to match-fixing, third-party ownership and the trafficking of minors.

"We thought the transfer system was finished on 15 December, 1995, but of course it isn't," explained Van Seggelen.

"In fact, the situation is even worse than before. I often say to people 'how would you feel if you had to wait three months for your salary?'

"You also have players waiting years for justice through the tribunal system, and even when he has a positive decision there is no enforcement system. We cannot accept that."

That might win over a few more voters on the terraces but there will still be many in the "Bosman ruined football" camp who think this is simply a union fighting for more money for its members, and in this case the members are loaded.

"Only 1% of our members are financially independent, so not every player is making that kind of money," said Van Seggelen.

"We're not trying to make them richer. In an ideal world, every player would play at the level they belong.

"I don't know why the clubs are so nervous. We are not trying to kill the top clubs or leagues.

"Sport is unusual but it must be reasonable. It's an economic activity, a business, so it must respect the law."

By this point, Bosman is outside smoking.

Despite arriving late and looking like he could not wait for the interview to end, he was good company.

He does not watch much football these days, he cannot afford the television subscriptions, but what he sees he enjoys.

His main focus is looking after his two young boys and being a better dad to the grown-up daughter he has from an earlier relationship.

"Martin and Samuel are too young to know about my case, I don't want to complicate their lives with it, they've just left kindergarten," he said.

"But I think later, when they grow up, they could find out about what their dad has done for professional players on the internet and they will see their dad has done something good.

"Back then clubs were selling hens, horses, mules and pigs, but not humans.

"Players should be considered as workers, full stop, that's it! This is the Bosman ruling, and we ought to get back to it."

- Published14 December 2015

- Published14 December 2015

- Published14 December 2015

- Published14 December 2015

- Published20 June 2016