Billy McNeill: The 'Luke Skywalker of his age'

- Published

McNeill captained Celtic to their famous European Cup win in 1967

As the world queues up this week to herald the return of Star Wars, a statue is being erected in the east end of Glasgow, which will be a reminder to those of us privileged to have been in Lisbon in 1967, that Billy McNeill was the Luke Skywalker of his age.

That moment on that sunny afternoon, when the exhausted figure in green and white managed to find the energy to lift the European Cup above his head,, external heralded the fact that a bunch of local lads, of whom little was known outside their own community, had brought down the evil empire of catenaccio football, external by beating favourites Inter Milan 2-1.

The achievement is now being given visible permanence in the east-end of Glasgow, just outside Celtic Park, where it will prove to be a distraction to drivers on the busy London Road but to those who treasure the club's history, a place of reverence amidst the hubbub of urban life.

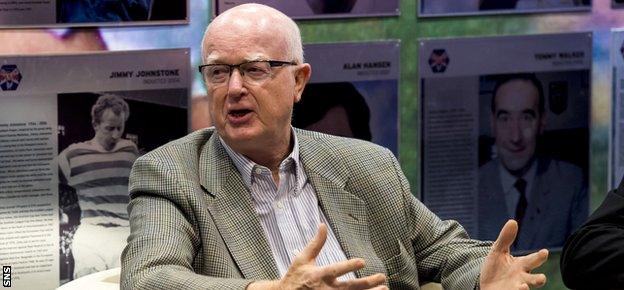

Archie Macpherson hails Celtic favourite Billy McNeill

It will also revive a treasure of personal memories surrounding the man who in working with me at the BBC, as co-commentator on a wide range of games, including the World Cup in Spain in 1982, became a close friend.

It will also remind me of that cup presentation which took place just in front of our commentary position in the Estadio Nacional.

I could see the strain on Billy's face: there was no sense of euphoria, just a weariness, as if he was glad it was all over.

After all, he had tried to fight his way through the crowds and had given up, and had to be transported around the stadium to climb up a back entrance to the rostrum.

It was only when he lifted the cup with a triumphant flourish that you felt the touch of the silverware had re-energised him. The Force was now with him.

Years later I went to his house to interview him before an Old Firm cup final. I asked if we could film his European Cup winners' medal?

He had to ask his wife Liz where it was. After some searching they discovered that in fact his daughter was outside in the garden playing with friends and using all his medals as currency, playing at shopping.

There was something in that tableau that revealed a lot about the man. For sure he gave the impression of arrogance at times on the field as he strode out onto the pitch, chest thrust out, almost as if he were staking a territorial imperative, and dare anyone come near him.

In fact, his head was never in the clouds. He put his triumphs behind him like a man puts his tools away before clocking-off.

Of course, he treasured his memories but in all the time I had with him it was never boastful, never self-indulgent, never crowing. Sometimes you had to drag memories out of him and when you succeeded you were listening to an eloquent raconteur.

"I will recall a lifetime relationship with Billy McNeill which I feel privileged to have enjoyed"

But letting his kids play with his medals with friends? How more natural and down-to earth could you be in allowing domesticity to trump days of glory?

He has always been easy to interview. The day he told me he was retiring from playing he gave me a chat that was filled unavoidably with nostalgia. It was after the winning Scottish Cup final against Airdrie in 1975.

It was devoid of mawkish sentiment, just a brief recounting of his career and looking forward to new challenges, whatever they might have been in his mind. It was then I asked him if he would be interested in some broadcasting.

He said he had other things in mind at the time and shortly afterwards we realised he wanted to enter management.

I certainly admit to having had some verbal clashes with him when he entered that new domain, firstly with Clyde, then Aberdeen, then Celtic.

But they never persisted, never running sores, which frankly I experienced with some others. It was when he was manager with Aberdeen that I realised how much he would have wanted to return to Celtic.

"Billy put his triumphs behind him like a man puts his tools away before clocking-off"

We were standing at the tunnel-mouth at Hampden about 45 minutes before Aberdeen played Rangers in the Scottish Cup final.

And, as he looked around at the vast Rangers support, he admitted to me that some of his players in his dressing-room were nervous wrecks, almost as if he were prophesying the outcome and unable to come to terms with this culture shock for him, being accustomed to defiance in a dressing-room on Old Firm finals.

He went to Celtic after that defeat at Hampden and when eventually he passed through Celtic twice and after managerial stints in England, I thought I had stuck gold when I convinced him to join me as co-commentator and pundit at the BBC.

He was always well prepared for matches. In short, he knew what he was talking about and although we sometimes disagreed about certain matters we always hoped that we struck the right tone between us.

This was especially so in the World Cup in Spain in 1982. He was with me on the platform when Jimmy Hill made his infamous "toe-poke" description of Davy Narey's strike against Brazil in Seville.

He almost swallowed his microphone. We went to dinner with Hill the night after and Billy took his revenge.

Instead of bringing that subject up he instead made play of the fact that Hill was complaining that he had not been included in the recent Queen's Honours list. "You deserved a Knighthood, Jimmy and I'm going to complain about that."

Billy McNeill toyed with Jimmy Hill following the latter's infamous Dave Narey "toe-poke" comment

He said that with such heavy irony that it got through to Hill that he just been toe-poked himself and shut up thereafter.

Several nights later he was beside me in Malaga for Scotland's last game in the group against the then Soviet Union, Scotland required a win to progress for the first time to the knock-out stages.

After a Willie Miller-Alan Hansen blunder which allowed the opponents to score, two Soviets, perhaps NKVD secret-service for all we knew, in front of us, got so excited they kept blocking our view of the game which added to our exasperation as we were feeling Scotland had blown it again.

I decided to remonstrate and eventually punched one of them in the back having tapped him previously without result. He then stood up. He was about 10ft tall and built like Dumbarton Rock; I noticed his fists were clenched.

I turned to Billy to see if together we could cope with Goliath. He, however, had slid under his seat, laughing helplessly.

Thus, I became aware his tactical nous went far beyond football matters. We survived and through the years he kept reminding me of the day I thought I was Rocky.

His humour stems from his working-class origins in and around Bellshill, and how it can help allay any fears or anxieties.

So, when I look at the statue to be unveiled on Saturday, I will recall a lifetime relationship which I feel privileged to have enjoyed.

- Published18 December 2015

- Published10 April 2015

- Published20 June 2016

- Published7 June 2019