Oculus Rift: How will virtual reality change watching and playing sport?

- Published

- comments

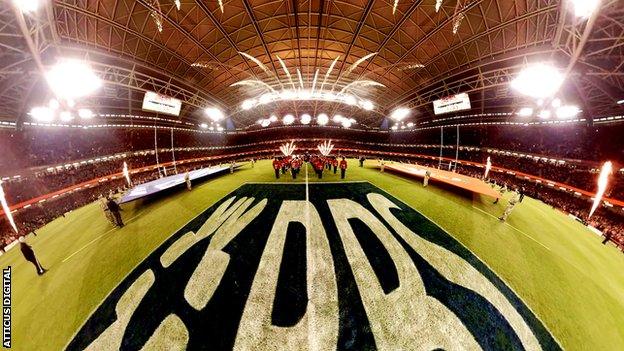

The national anthems in the Six Nations game between Wales and Scotland have been brought to life by 360-degree video

Watch England from a seat at Wembley without leaving your sofa? Throw a Super Bowl-winning touchdown pass from the back garden?

It's possible. Well, virtually possible.

The release last month of the Oculus Rift, a headset designed to make users feel as if they are immersed in a virtual world, brought the hypothetical closer to fruition.

Virtual reality has long been the enigma of the video game industry, with companies trying - and failing - to create successful VR since the early 1990s. But the Oculus Rift, HTC Vive, PlayStation VR and Samsung Gear VR - headsets that provide virtual reality experiences - are either here, or are about to hit the shelves, and their influence will not only be felt in the gaming sphere.

Already, professional athletes are stepping into the virtual world to help fine-tune their skills.

And before long, sports fans will be able to use the technology to take in a live event, as if they were there.

Can I watch sport through VR?

Atticus Digital used a 360-degree camera to film at the Principality Stadium

If you have a smartphone or tablet, you are already only a step away from seeing sport in a completely different way.

The increasing use of 360-degree cameras allows users, through apps like Facebook or YouTube, to watch footage back, moving the camera around by tilting and rotating their phone. The phone screen effectively becomes your eye into an event.

Atticus Digital has created videos for BBC Sport Wales such as a touchline view of the national anthems, external during the Six Nations, filmed inside the Principality Stadium.

"We're keen to get as close to the action as possible. Our aim is to get a 360-degree camera on a referee. I believe it would be amazing," says Martin McCabe, the company's director.

But none of that is live, unfolding sports action. It's pre-recorded, and there is a desire to watch as-it-happens sport from a virtual seat in a stadium.

Theoretically, you could then pay to sit in the Stretford End at Old Trafford while never having to leave your living room.

"Virtual reality opens up a whole new economic proposition for sports teams, and organisations will inevitably seek to make the most of that," says professor Andy Miah, an expert in new technology based at Salford University.

"A virtual landscape allows organisers to programme in more sponsorship so VR makes a really compelling way for sport to grow its economic investment."

The cost of VR | ||

|---|---|---|

Release date | Expected price | |

Oculus Rift | Released | £499 |

PlayStation VR | October 2016 | £349 |

HTC Vive | Released | £689 |

AMD Sulon HMD | 2016 | Not announced |

When will it happen?

This is where opinions differ.

Definitely not immediately - VR technology is expensive and often needs a high-specification PC to work.

"I really do think it will be less than five years. Possibly within the next two years," says Miah.

"The sets are big and bulky and you probably wouldn't want to spend 90 minutes watching a game in a headset. But as they become more user-friendly, people are more likely to keep them on."

Miah reckons most homes will have access to VR within three years, but Derek Belch - who created the sport-training VR system Strivr - is sceptical about the appeal.

"I'm not a huge believer in the concept," he says. "I think it will catch on some day - but the cameras are too far away and I don't think anyone wants the goggles on for two hours.

Sander J Schouten, business director of VR company Beyond Sports, points out that the lucrative Asian market, where many fans "will probably never get to a match in real life", could drive demand.

How can it help players?

Beyond Sport's VR system allows players to experience decision-making moments

The use of VR in professional sport is not entirely new.

The Netherlands football team - then managed by Louis van Gaal - trialled a system made by Dutch company Beyond Sports before the 2014 World Cup. Players could wear a VR headset and relive specific moments from a game through the eyes of a player. They can then make a decision. Should you have passed to the wing? Taken on the defender?

The system measures decision-making speed and allows coaches to talk through the best options.

PSV Eindhoven and AZ Alkmaar are current users of the kit - and there are others who choose to remain anonymous.

"You're sitting in an office or a cafe right now and you know how you got there," says Schouten. "Really good players have that same spatial awareness on the pitch but you can train it as well."

Sony's PlayStation VR has undercut its rivals. Its headset will cost £349 in the UK and $399 in the US.

How does it work?

Beyond Sports' system uses cameras around the pitch, combined with data about players' physiques, to recreate moments from play. It looks like a Fifa or Pro Evolution-style football video game.

But is it useful?

"It looks real - you're really in the stadium and when you look behind you, you see the keeper. This is what makes it such a good training tool," says Schouten.

"You can take the same moment and place it on a boy of 12 and see what he could do in the future based on that. Afterwards the coach can explain why he should've played a certain option."

Which other sports use VR?

Strivr's VR puts the user in the role of the quarter-back

While football has not embraced VR wholeheartedly yet, American football is further along.

Three years ago Belch, then coaching the Stanford University team, developed Strivr as part of his graduate training scheme. The Dallas Cowboys were the first NFL side to use it, and now there are five more, plus 12 collegiate teams.

"Athletes and coaches have always looked at gaining an edge," he says.

"Look at all the concussion stuff in the NFL - this allows you to train around that. It's only a matter of time before every major sport has some level of virtual training."

The Strivr system plays back pre-recorded set-pieces - such as the snap, when the quarter-back controls the play - in a completely 360-degree view in the VR headset. It allows players to repeat, over and over, a tactic, play or scenario, and gives them the ability to look anywhere on the pitch - as if they were on the field.

"Last year quarter-back starters would wear it out - watch something back 50 times," says Belch.

"In American football especially there is never enough time for practice. There's not enough time to get real reps - now there's a way."

Although Strivr works well for sports like baseball and American football where the scenarios are based around a static position - a quarter-back at the snap, a hitter or a pitcher - football presents more of a problem because VR has yet to fully solve the problem of moving around within a virtual world, particularly without the user feeling sick.

Know your VR terminology?

Leo Kelion, BBC News website's technology desk editor

Virtual reality: VR involves a user's vision being filled with computer-generated images or 360-degree views of stitched-together videos, which move as they tilt and angle their head.

360-degree video: A video recorded in a spherical format that captures views in every direction surrounding the camera or cameras. The video can be played back via a headset to allow the wearer to adjust their perspective.

Latency: The amount of lag between an action and the response.

Head and eye tracking: Most VR kit uses a range of sensors - including accelerometers and laser/light-tracking sensors - to determine the movements of the headset. This allows the footage to move in time with the motion of the user's head.

Binaural sound: There are also techniques to make sounds appear to be happening around the user rather than coming from inside their head. Try listening to this binaural sound experiment, external with your eyes closed to get an idea of what it is like.

What about the social experience?

"Where virtual reality in the past was just about our perspective on some unreal space, its future is all about social experience," argues Miah.

"You should be able to sit in a virtual arena and look to your left or right and have a conversation with someone else who is also present in the virtual experience."

And what about the professionals? Are we doomed to watching robot athletes, trained to perfection by virtual reality tools?

Belcher still sees a world where youngsters know what it's like to feel the sensation of putting boot to ball.

"I always tell people let's not stop practising. Let's not make everything virtual. Let's still get kids running outside."

- Published20 June 2016

- Published7 June 2019

- Published2 November 2018