Mental health: Players' union PFA says 'more and more' players seeking help

- Published

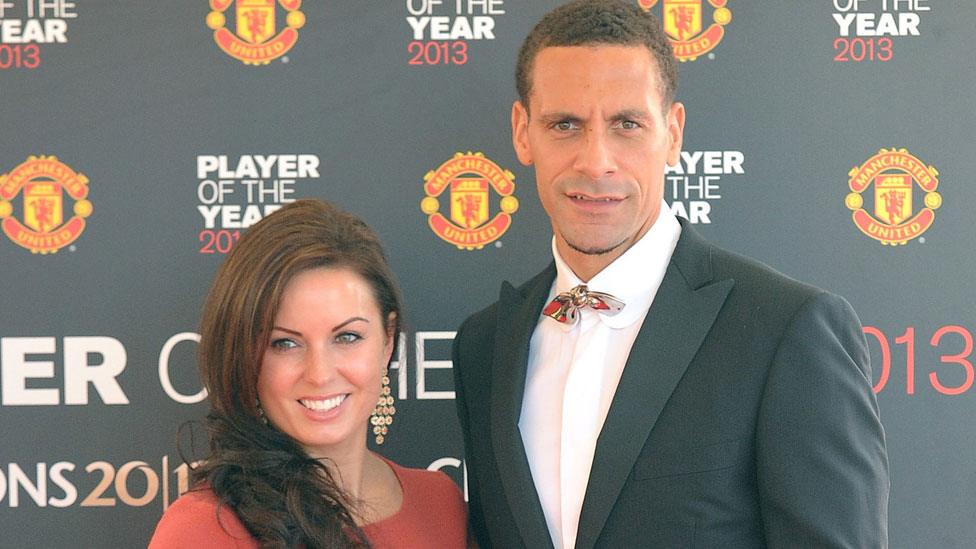

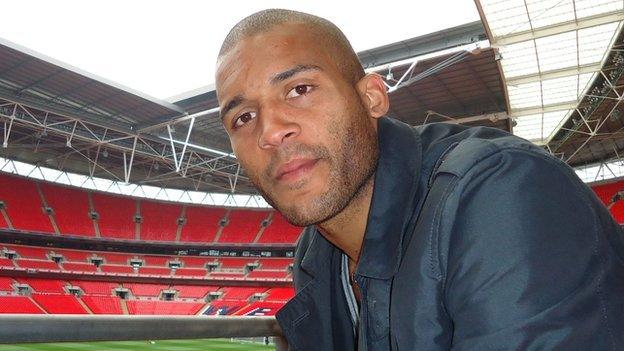

High-profile cases like that of former Burnley defender Clarke Carlisle have helped more players to speak openly about their problems, the PFA says

The number of players seeking help for mental health problems is increasing as awareness of the issue grows, says the Professional Footballers' Association.

Everton winger Aaron Lennon is currently receiving treatment for a stress-related illness after being detained under the Mental Health Act.

Last year, 62 current and 98 former players requested support from the PFA player welfare department.

"That is growing year on year," said PFA head of welfare Michael Bennett.

"Key for me is making our members aware of what is in place, and the more we raise awareness the more people will use the service.

"We are telling them it's OK to talk and there is plenty in place to support them when they do come forward."

Despite being taken to hospital for assessment, Lennon, 30, is not suffering from a long-standing mental health issue and is expected to make a full recovery in the short term, BBC Sport understands.

Bennett said former players and high-profile figures such as Prince Harry talking about their experience of mental health issues "brings the taboo down" and helps to change the "male mindset that it is seen as a weakness".

Former England captain Rio Ferdinand discussed his experience of grief after losing his wife Rebecca to cancer in a recent BBC documentary, while former Burnley defender and ex-PFA chairman Clarke Carlisle has spoken out about depression and suicide in professional sport.

"We are trying to change that mindset because if you were to twist an ankle or pull a hamstring - because you can physically see it - you can treat it," added Bennett.

"But because mental illness is something you can't see it is not viewed the same."

The PFA's player welfare department was set up in 2012 and offers a range of support options, including a 24-hour phoneline and access to a psychiatrist.

- Published3 May 2017

- Attribution

- Published27 March 2017

- Attribution

- Published17 April 2017

- Published5 February 2015

- Published25 March 2015