Confederations Cup: World Cup host Russia set to come under spotlight

- Published

Host nation Russia play New Zealand in Saturday's opening fixture, a 16:00 BST kick-off

With a year still to go before the 2018 World Cup begins, it may be that thoughts of next summer's tournament are far from the front of your mind.

But the Fifa Confederations Cup, which gets under way in Russia on Saturday, might change that - and not just because of the football.

Many of the issues that surround Russia's hosting of the World Cup are likely to come under the spotlight over the next few weeks, as teams from around the globe compete at Fifa's test run.

Questions over hooliganism, corruption allegations and claims workers have been abused provide a complex background to the eight-team event.

Even if you think the Confederations Cup is nothing more than a series of glorified friendly matches, there is still a trophy to be won.

But in many respects it is Russia's success at hosting the World Cup test run that is of most interest.

Why is there so much focus on Russia?

Ned Ozkasim: 'A lot of the English fans tried to run away'

Last summer, as fans tumbled down the Stade Velodrome slopes in the violent chaos that followed England's 1-1 draw with Russia at Euro 2016, a Russian MP praised the "patriots" who had "brought honour to their country" in Marseille.

"I don't see anything terrible about fans fighting. Quite the opposite, the guys did well. Keep it up!" said Igor Lebedev, a member of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia.

Lebedev's party exists on the fringes of a democracy dominated by president Vladimir Putin's United Russia. But he is also a board member of the Russian Football Union, and what he said was reflective of a new evolution in hooliganism and attitudes towards football violence in the country.

Both ordinary England fans and fellow hooligans were targeted by hundreds of Russians in the south of France. Some wore gum shields, others were equipped with body cameras to capture the violence.

The Russians had shown themselves to be fitter, faster, more brutal and better organised. And this seemed to be a cause for celebration.

"This showed who is the most important among hooligans," one Russian man involved in the fighting told the BBC. "In the 70s and 80s everyone would bow down before the English. Now there are different hooligans. These are different times."

But what about the ordinary fans?

Man Utd fans, 238 of them, watched a 1-1 draw in the south of Russia in early March

In February, a BBC documentary team travelled to investigate. Russia's Hooligan Army featured interviews with the Orel Butchers, a group who played a key role in the organising, execution and celebration of the huge brawls that took place across Marseille.

"We were seeking honour, pride in the fight," one man said. Another said next year's World Cup would be "for some a festival of football; for others, a festival of violence".

The Panorama programme also went to Rostov in the south of Russia, where they filmed organised fights between rival fans arranged in remote woodland.

A month later, in March, a few hundred Manchester United fans were in the city for a Europa League match. There may have been concerns over the reception they would receive, but there was no violence and no co-ordinated attack. Instead, Rostov fans handed out red blankets to the travelling English support.

A week later, Spartak Moscow fans displayed two enormous banners in an away game at city rivals Lokomotiv Moscow. In one, the initials of the BBC stood to mean the Blah-Blah Channel.

Another had the three initials that referred, in Russian, to Bolelshiki Bolshoi Straniy - which means fans of a big country. It contained the hashtag #WelcomeToRussia2018 and the point seemed to be that not every Russian football fan wants to fight, and some are fed up of being portrayed that way.

Spartak Moscow fans held up two banners at a derby match with city rivals Lokomotiv Moscow

A second banner was unfurled after half-time, where the letters BBC stood for 'Fans of a big country' in Russian

'One incident can overshadow a lot of good'

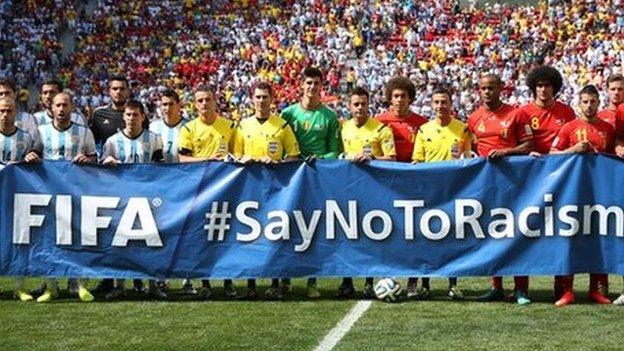

Former Arsenal player Emmanuel Frimpong spent three years in Russia, first playing for FC Ufa near the border with Kazakhstan and later for Arsenal Tula, based not far outside Moscow. He says hooliganism was never an issue in games he played in - " I think I saw one" - but something distasteful did happen to him; he was racially abused when playing at Spartak in 2015.

A small group of fans targeted him with monkey chants, and when he reacted by showing his abusers the middle finger, he was sent off by the referee. He was banned for two games by the Russian Football Union (RFU), which took no action against Spartak.

Former Arsenal midfielder Frimpong is now playing for Swedish top-flight side AFC Eskilstuna

At the time, Frimpong's reaction was to tweet: "I'm going to serve a sentence for being abused, and yet we are going to hold a World Cup in this country, where Africans will have to come."

Looking back now, he repeats his belief that the league's decision to suspend him was "pathetic", and that they failed to use it as an opportunity to help stamp out racist abuse and discrimination. But he also stresses - repeatedly - that he loved his time in Russia, and that in his daily life he never felt vulnerable to abuse over the colour of his skin.

"That day was a one-off," he says. "In Russia the experience I had was not a bad one in terms of racism at all. There are people who don't often see a black person, so sometimes they tend to stare. They tend to ask questions about what you are doing here, why would you come to Russia because it's so cold, but it's because they are interested. I still have so many friends from my time there.

"Every country has a problem with racism. Most of the Russians have a good heart and respect people, but obviously there are a couple who are different. It's difficult. The thing is that one incident can overshadow a lot of good."

Weren't there other cases of racist abuse?

Unfortunately, what happened to 25-year-old Frimpong is not an isolated case in recent Russian football history. In 2015, the Fare network,, external which monitors discriminatory abuse in football, published data highlighting more then 200 incidents between 2012 and 2014, and Fifa said racism in the Russian game was "completely unacceptable".

Former Zenit St Petersburg striker Hulk said he was racially abused in "almost every game" he played in Russia, while ex-Burnley defender Andre Bikey said he carried a gun, external for protection during his two years with Lokomotiv Moscow from 2005.

The Orel Butchers support Orel FC, who were relegated from the Russian third division this season

Fare is about to publish new figures - again in tandem with the Moscow-based Sova Centre, which has seen its work stifled, external by a Russian law that Amnesty International says is used to "shackle and silence", external organisations deemed to be working against government interests.

Speaking before the latest data was published, executive director Piara Powar told BBC Sport that Fare remains "seriously concerned" over the evolution of the hooligan movement in the country, and its links to far right extremist groups.

What is Russia doing now?

In February, the RFU appointed former Chelsea midfielder Alexei Smertin as chair of its anti-racism taskforce. Two years earlier, he told the BBC that racism "does not exist" in Russia.

Speaking to BBC News' Moscow correspondent Sarah Rainsford this week, Smertin said he was confident the country would see no incidents of racism during the Confederations Cup or World Cup.

"I would say there is this tiny minority of people who are a bit aggressive," he added. "But 99% of people who love football are quite polite."

Russian football's anti-racism inspector Alexei Smertin once denied the problem existed there

Also this week, the Russian Interior Ministry announced it has banned 191 nationals from attending matches - almost double the number that were banned before Euro 2016 - while a new "fan passport" requires all ticket holders for the Confederations Cup to go through security checks.

While referees will be given the power to abandon games if they witness any discrimination from fans, anti-discrimination observers trained by Fare will monitor behaviour inside the grounds.

Fifa's head of sustainability Federico Adiecchi has been working closely with the 2018 World Cup organising committee and the RFU on issues of diversity and anti-discrimination.

He told BBC Sport the process has been "a very positive one".

"We are confident in the work that is being carried out in Russia, the measures we have put in place and the assurances we are getting from government level that the Confederations Cup and World Cup will be inclusive and safe for everyone," he said.

Fare's executive director Powar believes "there is no question" authorities are acting to address "what they know is their Achilles' heel".

"The Russians will do their best to protect fans. It's a huge opportunity for Russia to put itself in the shop window, to show it is capable of putting on an event of this kind," he says.

But he adds: "It doesn't feel like there is a lot of enthusiasm for Russia from English fans, and some of those fears they are quite right to hold."

Cycling bears and workers' rights

A military historical festival was recently held at the new 'Saint Petersburg' football stadium

Looking out on the Baltic sea, St Petersburg's new 69,000-capacity Krestovsky Stadium is almost 9,000km away from the Russian Premier League's newest arrivals, FC SKA-Khabarovsk, who are based just down the road from China. London to Los Angeles is closer.

This will be the setting when Russia take on New Zealand at 16:00 BST in the opening game of the Confederations Cup on Saturday.

The ground has been under construction since 2007, for a long time behind schedule and over budget. Transparency International, external - which monitors corruption around the world - has described it as "a Klondike for St Petersburg officials".

When the ground finally held its first test event in February it still was not ready. The roof was leaking, but 10,000 people were treated to an evening's entertainment that apparently included a cycling bear., external

Transparency International calculates the total spent on the stadium at $1.35m (£1bn), nine times the original budget, and Dmitry Sukharev, head of its Russia office, told BBC Sport the budget had been allowed to grow "without any transparency and without controls".

"Increasing the cost by nine times is a disaster for any construction project", he wrote via email.

"Many schemes were conducted through subcontractors, which were in fact firms through which money was laundered. The officials involved in the construction, I am sure, took part in these schemes directly."

But allegations of corruption - which the local and national government has denied - is not the only problem surrounding the arena.

The Krestovksy Stadium will be Zenit St Petersburg's new home, and hosted league games towards the end of the season

In May, Fifa's president Gianni Infantino wrote to the Norwegian, Swedish, Danish and Icelandic football associations to address concerns they raised over a Norwegian magazine (Josmiar) report that claimed North Korean migrant labourers were being forced to work in dangerous conditions.

On Wednesday, Human Rights Watch, external published a wider report detailing further claims of workers' rights abuses at five other new World Cup 2018 stadiums.

The report cited the Building and Wood Workers' International global union as saying 17 workers had died across the sites. It said many more were "afraid to speak out" over the "exploitation and abuse" they faced.

It criticised the monitoring programmes Fifa set up in partnership with the Russian government, and called on the governing body to "move away from the secrecy that has plagued its operations" and "show it can achieve meaningful protections for workers, be transparent and accountable".

Fifa has defended itself from the claims. It says it has "gone beyond what any sports federation" has done before in terms of its work on human and labour rights, adding that the report "does not correspond" with its own assessments, based on multiple site inspections.

Will there be giant ducks?

St Petersburg was built as a window on the west. Peter the Great, a towering 6ft 8" Tsar obsessed with leading Russia towards modernisation, was its founder. He came back from an incognito tour of London's dockyards and Manchester's factories inspired to establish a new city, in 1703.

By the time the World Cup comes around, it should have another new building - the Lakhta Centre, a new headquarters for Gazprom that is planned to be the tallest building in Europe.

There will also have been a presidential election - the next one is scheduled for March 2018.

Putin has not said he will be standing but is widely expected to do so. On Monday, Alexei Navalny, who does intend to stand and has begun to mobilise popular opposition support, was arrested for repeatedly violating laws on staging rallies.

In May, Putin's government passed a law banning public protests from being held in Confederations Cup host cities between 1 June and 12 July.

But that did not stop thousands of Russians attending in Moscow and St Petersburg on Monday, where ducks were out in force again - rubber ones, real ones, giant inflatable ones that were led away by the police.

That's because Navalny's supporters have adopted the duck as a symbol since nationwide rallies in March, where they called for the resignation of Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev over allegations of corruption.

The allegations included the accusation that Medvedev had a special house for a duck on one of his properties, claims he has described as "nonsense".

And what about the football?

Eight nations are competing at the Confederations Cup, with the teams split into two groups of four. Group winners and runners-up meet in the semi-finals, with the final to be held in St Petersburg on 2 July.

Ronaldo's Portugal will play Russia, New Zealand and Mexico in Group A

Real Madrid striker Cristiano Ronaldo will be playing for Portugal alongside Manchester City's new signing Bernardo Silva, while Arsenal's Alexis Sanchez is in the Chile squad.

World champions Germany - in a group with Cameroon, Australia and Chile - have named seven uncapped players in a squad that includes Arsenal's Shkodran Mustafi, Liverpool's Emre Can and Manchester City's Leroy Sane.

Group A:

Russia, qualify as 2018 World Cup hosts

New Zealand, 2016 OFC Nations Cup winners

Portugal, Euro 2016 winners

Mexico, 2015 Concacaf Cup winners

Group B:

Cameroon, 2017 Africa Cup of Nations winners

Chile, 2015 Copa America winners

Australia, 2015 Asian Cup winners

Germany, 2014 World Cup winners

- Published14 June 2017

- Attribution

- Published15 June 2017

- Attribution

- Published15 June 2016