Kenny Dalglish on Liverpool - the club, the fans, the city, and Hillsborough

- Published

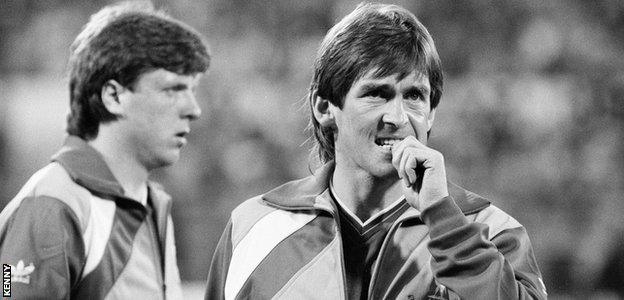

Kenny Dalglish scored 172 goals in 515 games for Liverpool

The first thing you notice about Kenny Dalglish is the handshake. It's like being held in a warm vice. The second thing is the smile, which you notice more because this one you weren't expecting.

The Dalglish grin is a big one, crinkling his eyes, slow to leave, especially when he's talking about Liverpool, the city and football club, and Glasgow, and a life that linked the two football-obsessed cities together.

Three years from his 70th birthday, Dalglish - voted Liverpool's greatest ever player and the most capped Scotland international of all time with a share of the record for the most goals scored - is the subject of a new biopic, which is in turns stirring and self-deprecating, gently humorous and inextricably defined by tragedy, just like the man himself.

For a football superstar who always lived a public life with intense privacy, it is also surprisingly revelatory. Twenty-seven years on from last kicking a ball in a competitive match, and five from his last dalliance with management, Dalglish has been looking back into the past, sometimes reluctantly, often painfully, frequently with a fresh pleasure.

Liverpool managers must be humble - Kenny Dalglish

Some strikers today celebrate goals with pantomime anger, or an admonishing finger, or a self-aggrandising pose. When you return to Dalglish's best strikes for Celtic, Liverpool and Scotland you see simple joy - both arms up, that big grin on his face, creating his own footballing glee club with his team-mates and the crowd all around.

"For us, we shared everything with the supporters," he says. "Shared the emotions with them, whether they were good or bad.

"They supported us and we tried to do our bit. There were thousands of them who would have loved to have been on that pitch. So why could you not share it?

"It was a privilege to even go there and play. It was a privilege to win. The way I looked at it, the club were doing me a favour. Not the other way round."

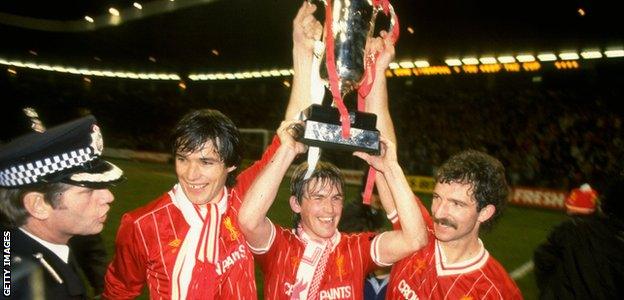

Dalglish scored 167 goals in 320 games for Celtic. As solely a player for Liverpool between 1977 and 1985 he won three European Cups, five league titles and four League Cups. As their manager he took them to three more league titles and two FA Cups, including a league and cup Double in his first season as player-manager in 1985-86. You might think the privilege was all the other way round.

You might think too that the humility would be carefully cultivated. But it is there not only when he talks about the trophies and the goals and the titles but when he discusses, reluctantly, his role in the aftermath of the last of the three football disasters that he witnessed first-hand.

"I would be a player rather than manager every day of the week. That's the best part, the most enjoyable."

Dalglish was at Ibrox when 66 Rangers fans were crushed to death on a staircase in 1971. He was in the dressing room at Heysel in 1985 when 39 supporters died when a wall collapsed before the European Cup final. And he was on the touchline and then the pitch at Hillsborough on 15 April 1989, a day that for so many has dominated everything else since.

The most affecting scene in the film sees Dalglish drive back across Snake Pass to a hill outside Sheffield. He parks his car, gets out and walks to a point overlooking the distant ground, unable to bring himself to go any closer, despite returning to Hillsborough as a manager with Liverpool, Blackburn Rovers and Newcastle United after the disaster.

As he stares down at the blue stands and the floodlights, the eyes narrow and the tongue comes out and his jaw tightens, a man not just haunted by what he witnessed but seemingly back there on the pitch once more, seeing it fresh all over again, powerless, stricken.

"Well, that was as close as I was prepared to go," he says, voice dropping, sparkle extinguished.

"You'll never ever forget what happened there. So… I wouldnae go back. Whether that's right or wrong, I'm not really bothered. It's right for me, and that's what matters. I wouldnae go back to any of them, except Ibrox, and that happened on the staircase, off the terracing, so really you couldnae see what had happened there.

"But if it hurt us, it never hurt us as much as it hurt the families who were involved. Just imagine what they have gone through. They've sacrificed their lives. For us, for me, it's hard to take it. But we've got to get on with it, and we've got to show our strength and support for the families."

I can't go back to Hillsborough - Kenny Dalglish

In the aftermath of Hillsborough Dalglish tried to once again lead by example. At one stage he was going to four funerals a day. Under his bed he kept a box of letters written by bereaved Liverpool supporters.

In the film his wife Marina and daughter Kelly talk about the impact it had on him - the rash that covered his body, the inability to sleep, the moods and the anger, the struggle to make simple decisions that eventually led to his resignation as Liverpool manager in February 1991.

It would now be called post-traumatic stress disorder. Dalglish is still unwilling to admit to any of it, loathe to concede he suffered at all compared to others, unwilling to accept that the way he behaved meant a great deal to those who had lost so much.

"We only did what someone else would have done," he says at one point in the film. When I suggest that many think he did so much more, he is almost indignant in his refusal to accept commendation.

"Well, everyone's entitled to their opinion, and they can be judgemental if they want. The way that both Marina and I have been brought up was to give help to people if we possibly could.

"They had been totally supportive of us, the fans at Liverpool. So why shouldn't we have behaved like that?

"And it's not just myself and Marina. The other players and their wives were involved as well. Peter Robinson and the directors. Everybody jumped in. If you're a football club that sticks together, then that was the epitome of a football club respecting its supporters. I don't think that bond should ever be broken between players and fans."

Dalglish and his wife Marina set up the Marina Dalglish Appeal in 2005 after Marina was successfully treated for breast cancer in 2003

His son Paul came through the Leppings Lane turnstiles on that dark afternoon. Twenty-eight years on, he says his father has still never spoken to him about any of it.

"We're always a close family," says Dalglish Sr, eyes hooded, the old guard back in place. "But being a close family doesn't necessarily mean you're going to talk about everything like that every time you're sitting at the dinner table.

"I just don't feel any need to speak to Paul about it. Everybody knows it's there. If he wants to read about Hillsborough, he can read about it.

"Kelly and Paul and I walked together through the Kop on the Friday before they shut it, so I think that's more than I could speak in words to them. That showed them everything about the football club.

"You have to deal with it, so we dealt with it. Whether you dealt with it good, bad or indifferent, I suppose other people can judge that. But we dealt with it the best way each individual one of us could.

"Whether it came to closure, for each and every family, whatever they wanted, whatever they thought was best suited to them for closure, they should have that. And the same for us - we dealt with it as best we possibly could, and the players and everyone else involved dealt with it in their own ways."

As a Liverpool player and then manager from 1977-91, Dalglish won seven First Division titles, three European Cups, two FA Cups and four League Cups

Dalglish, in the cliche, is football royalty, still King Kenny to the Anfield faithful no matter how that last managerial stint ended. The crown is reluctantly worn, a consequence not only of a working-class upbringing in the north of Glasgow but of the dynasty he inherited when he moved south to another grizzled old port city.

"I don't think Liverpool could ever have anyone who didn't quite understand, never have anyone in who wasn't quite humble and straightforward. That's the template that was set before, by Shanks, by Bob Paisley, by Joe Fagan.

"They were all humble men, and I think it's gone on in that line. If you came in and you were something different, I don't think the dressing room would take it. If you were a wee bit put yourself forward before anyone else, you wouldn't have lasted either.

"It was brilliant the way it was. Everyone got on really well. Everybody was an equal, even though in outsiders' eyes they might not have been. Where it mattered, in the dressing room, on the pitch, they were equal.

"The managers were so humble it was frightening. And there's nothing wrong with being humble. There's nothing wrong with being appreciative."

Even Dalglish's decision to accept the Liverpool manager's job, as Fagan stepped down in the summer of 1985, is laced with a mixture of modesty and happy disbelief that any of this was happening to him.

"Well, I was only 34. I thought I was playing OK, but they must have thought otherwise.

"The only question I ever asked was 'why?' But I never asked them that, just in case they changed their minds.

Hard act to follow: Dalglish was brought in to replace the departing Kevin Keegan at Liverpool in 1977

"The thing that everyone who's been involved in Liverpool Football Club would say is that the one person to thank above all is Bill Shankly, because he set it all off. And he set the principles in place for everybody. When he left, Paisley took over. When Bob left, Joe Fagan took over. And unfortunately then I took over - the unfortunate bit being for Liverpool."

He grins. You did all right, I say - the Double in your first season, scoring the goal at Stamford Bridge that sealed the league title on the final day, rebuilding the team into one of the finest ever in English football, Barnes, Beardsley, Aldridge and the rest behind that 5-0 demolition of Nottingham Forest in April 1988…

A shrug. "For me, I'll always think that I was more fortunate rather than good."

He carries on in the same vein. When I say he began at Liverpool like an express train, he laughs and pats his comfortable spread.

"Nah, I wasn't that quick."

A freight train?

"Aye. Heavy goods train. Aye."

The Merseyside derby that caused Dalglish to quit

In all of it the love of football comes through, a lifelong affair that still has the same grip as it did on the kid trying to break into the Celtic team under Jock Stein or the bashful superstar who replaced the more naturally charismatic Kevin Keegan at Liverpool under Paisley at Anfield.

"I would be a player rather than manager every day of the week. That's the best part, the most enjoyable. The camaraderie, the dressing room, the banter, the boys… If you've got a problem, somebody in there will have a worse one. You share it all together, and that was fantastic.

"I was fortunate to have two magnificent clubs, two very successful teams. Fantastic people, like Jock. And when I left Celtic, I had Bob. Nobody could have picked two more successful managers to play under than I did. Except I never picked them, they picked me.

"For me, growing up, playing at Celtic, was fantastic, being a Glasgow boy. And when you're young, 20 years of age for a league debut against Rangers, and you get told to take a penalty kick, and fortunately you get it in the net…

"You play for your national team, you come down and you play for Liverpool. Liverpool, who I'd seen a documentary about when I was 15, during the Home Internationals, and I arrived and it was just the same.

"I knew that the only person who could make this fail would be myself. It's been a fantastic city for us, and I just hope that in some way, shape or form, that we've repaid that gratitude to them."

There is time for one more big grin, as the farewell handshake mangles your feeble grip.

"You've seen the film?"

Yes.

"Aye. Well, I haven't seen the ending, so don't spoil it for me."

- Attribution

- Published13 May 2016

- Attribution

- Published26 April 2016

- Published16 May 2012