Walter Tull: The incredible story of a football pioneer and war hero

- Published

Walter Tull, footballer and British black war hero

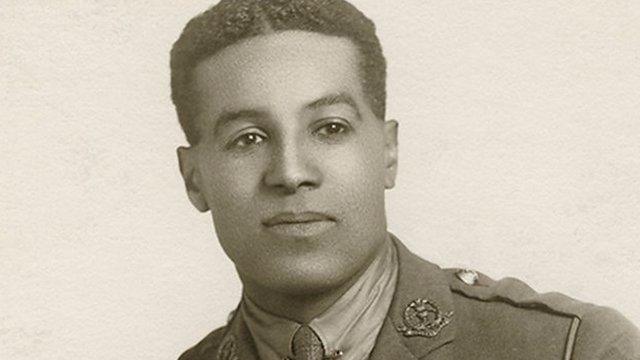

He was one of English football's first black players and the British Army's first ever black officer to command white troops.

But 100 years after he died aged 29 on the battlefields of World War One, the name Walter Tull means little to most people.

Tull was an orphan who had to overcome adversity all of his life, including being racially abused while a pioneering forward for Tottenham Hotspur and Northampton Town.

His death received little media attention at the time, and it is only in recent years that his powerful story has started to be fully recognised, in large part due to the work of historian and biographer Phil Vasili.

A campaign for Tull to be awarded the Military Cross is ongoing, with renewed calls for the prime minister to intervene.

This is the forgotten story of a footballer and war hero.

Tull enlisted with Middlesex Regiment, part of a 'Footballers' Battalion'

The obituary of Walter Tull, 100 years on

Second Lieutenant Walter Tull died while engaged in combat near Arras in Northern France. He was 29.

In the early hours of 21 March 1918, a fog hung over much of the British line on the Western Front in France.

At 4.40am, a German bombardment began. It was of a different order to any that had come before it.

It marked the start of what became known as the German Spring offensive - a last throw of the dice to turn the war in their favour and score a decisive breakthrough.

Over the next five hours more than 6,600 German guns fired 3.5 million explosive shells on British positions. The sound could be heard as far away as London.

Into the midst of this death, destruction and chaos came Walter Tull, an officer of the British Army in spite of his "non-European" heritage, which should have barred such a commission.

With the British Army fighting a fierce rearguard defensive action, Tull was shot and killed.

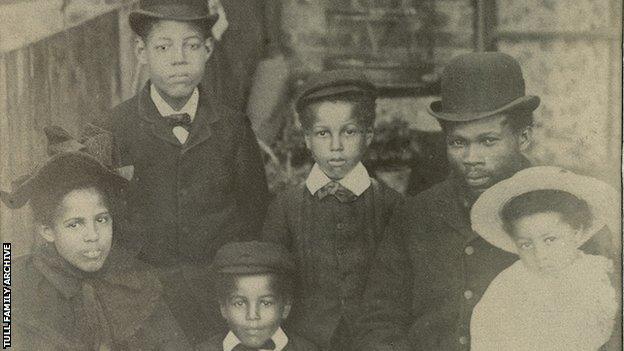

Tull's mother and father passed away just two years apart

Tull had played many roles throughout his short life: a brother, a son, an orphan, a footballer, a soldier, an officer and, finally, a war hero.

At every stage he had to overcome adversity and challenges - obstacles he refused to let define him.

Born in Folkestone, his young life was marked by tragedy when his mother, Alice, died of breast cancer when Tull was just seven.

Two years later, his father, Daniel, passed away of heart disease.

Daniel Tull had arrived in Britain from his native Barbados in 1876 having worked his way over as a ship's carpenter.

The death of both parents left their children facing severe financial difficulties. Walter and his brother Edward were eventually taken in by an orphanage in Bethnal Green, part of an organisation known today as Action For Children.

"Walter and Edward found themselves in the most precarious and vulnerable position," says the charity's chief executive Carol Iddon.

"They were welcomed into a national children's home, where staff encouraged Walter's love of football - helping to shape both the life he would lead and the man he would become."

The brothers were together and kept in contact with the rest of their family back in Folkestone.

Further trauma was to befall Tull, though, when he and his brother were separated through Edward's adoption by a couple from Glasgow.

Now alone in the orphanage, Walter excelled at sport and went on to play for amateur team Clapton FC.

Tull's career at Spurs drifted due to the racial abuse he suffered

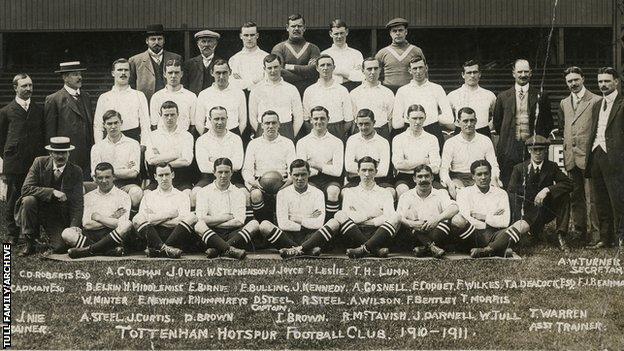

Spotted by Tottenham Hotspur, he was soon playing at White Hart Lane in front of crowds in the tens of thousands.

One of the first black players in the English game, he was subjected to terrible racial abuse. One newspaper report at the time described how, during a match at Bristol City in 1909, "a section of the crowd made a cowardly attack on him in language lower than Billingsgate".

The reporter wrote: "Let me tell those Bristol hooligans that Tull is so clean in mind and method as to be a model for all white men who play football. In point of ability, if not actual achievement, Tull was the best forward on the field."

His career at Spurs drifted following the racial abuse he suffered. Confined to the reserves, his fortunes were revived when Herbert Chapman signed him for Northampton Town in 1911 for a "substantial fee".

He went on to play 111 games for the club before the outbreak of World War One took his life down a radically different path.

Tull was cited for "gallantry and coolness" after leading a night raid with 26 men

Tull enlisted with Middlesex Regiment, part of a 'Footballers' Battalion' that drew professional players from a range of clubs.

He fought extensively in the war, at one stage being sent home suffering from "shell shock" - what today would be diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder.

He returned to the conflict, having been made an officer, and served on the Italian Front from November 1917 to early March 1918.

It was here he was cited for his "gallantry and coolness" by Major-General Sydney Lawford, after leading 26 men on a night raid against an enemy position. He and his men crossed the cold River Piave into enemy territory before returning, all unharmed despite coming under heavy fire.

Major Poole, the commanding officer of the 23rd Middlesex Regiment, and 2nd Lt Pickard said Tull had been put forward for a Military Cross. Pickard wrote Tull "had certainly earned it".

His family are still waiting for that medal to be awarded but Tull's great nephew Ed Finlayson is keen that a renewed focus on Tull's life focuses on more than the issue of the Military Cross.

"We have seen the creation of educational materials, publications, community projects, activities in the arts and sport - including dramas, plays, and documentaries - concerning Walter's life and issues of inequality and discrimination," he says.

"This year of centenary may provide a particular spotlight on his story and life.

"If aspects of his life have been helpful in supporting and promoting the need to challenge inequality and discrimination - and perhaps provided some encouragement in this endeavour - you hope this will not diminish once the centenary of his death has passed."

Such activities have included the #Tull100 campaign, external, a government and Lottery-funded initiative that aims to use Tull's story to boost community cohesion and inclusivity. A range of projects are taking place across the country backed by the Football Association, the Premier League and the EFL.

Tull's death was therefore not the end of his impact on British society.

But he was not to know this in the chaos and confusion that followed the enormous German offensive of March 1918.

Such was the ferocity of the attack, the British Army had considered falling back to defend the Channel ports given the pressure they were under and the huge loss of life. British and French forces suffered a combined 250,000 casualties but, ultimately, the Germans ran out of momentum and the tide of the war was to eventually turn irrevocably against them by November that year.

On 25 March, Tull was shot and fatally wounded.

It is reported Private Tom Billingham - a former goalkeeper for Leicester Fosse - attempted to drag Tull's body back to the British position so he could be buried. His efforts failed and Walter's body lay in the soil of northern France, like so many that fought and died in the Great War.

Tull's life is now commemorated at the Arras Memorial, meticulously maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves. His name is engraved along with 34,785 other soldiers with no known grave, who died in the area between the spring of 1916 and 7 August 1918.

A lasting memorial and remembrance garden in the shadow of Northampton Town's stadium also remembers the life of one of Britain's most unknown and under-appreciated heroes.

The Walter Tull Memorial

With thanks to Phil Vasili, Tull's biographer and author of "Walter Tull - 1888 to 1918, Footballer and Officer" (London League Publications)

- Published24 March 2018

- Attribution

- Published3 September 2014