World Cup 2018: How Gareth Southgate's team came to represent 'modern England'

- Published

England reached the World Cup semi-finals for the first time since 1990

London-born poet and writer Musa Okwonga, the son of Ugandan immigrants, looks at how England's multicultural team captured the imagination of a nation and became role models for young people.

England's football team, as it prepares to make its way home from the World Cup, has done something almost as impressive as claiming the trophy itself: it has captured the hearts of even the most sceptical people in the country.

Those people, long accustomed to heartbreaking disappointment when it comes to the country's football fortunes, saw something entirely different this summer: a group of players playing to the very edge of their potential, and beyond.

They also saw, in the words of manager Gareth Southgate, a team which in its youth and diversity represented "modern England". In terms of race and background, Southgate's players were as varied as you might find at a convention of YouTubers or on the line-up of the Wireless Festival.

At the start of the World Cup, the Migration Museum, external released a graphic showing how different the England team would look if first and second-generation immigrants were removed from it. The graphic, which quickly went viral, showed only five players would remain from the current line-up.

The Migration Museum's graphic that showed the impact of immigration on England's starting line-up

The changing face of the country can best be seen by looking back to the previous times when England similarly stirred the affection of their compatriots. In 1966, when they claimed the World Cup for the first and only time, it would be another 12 years until a black player would make an appearance for the England team in a full international.

For most of the 1980s, John Barnes was one of the strongest bonds that immigrant communities like mine felt with the national side, seeing ourselves in him as he speed-skated down the wing, shrugging off racist insults with a drop of the shoulder.

By 1990, when England were eliminated at the semi-final stage by West Germany, their line-up included Paul Parker and Des Walker, two footballers of Caribbean heritage.

In their semi-final loss to Croatia on Wednesday, five of their starting players were of Caribbean heritage, with one - Raheem Sterling - born abroad.

When Southgate spoke of this team being the face of modern England, he was somewhat ahead of the curve, given the black population of England (according to the 2011 Census) is 3%. A further challenge down the line will be the Football Association's development of Asian heritage players, given that this percentage of the population stands at 8%.

In one sense though, Southgate's team does offer a compelling and positive glimpse at the future - where disparate groups of people can come together and produce performances that most observers thought beyond them.

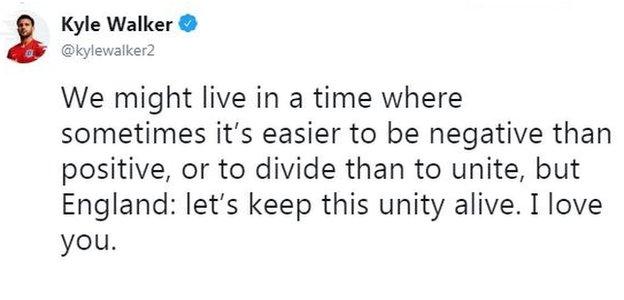

It might seem strange that so many have seen such symbolism in this team, but that's just a reflection of the uncertain period we are living in. Kyle Walker, one of the team's centre-backs, tweeted as much the day after the loss to Croatia.

"We might live in a time," he wrote, "where sometimes it's easier to be negative rather than positive, or to divide than to unite, but England: let's keep this unity alive. I love you."

Another reason this team may have captured the imagination is its regional diversity.

In a country whose focus can often be London-centric, it is refreshing to see players who hail not only from the capital but also from Yorkshire, Greater Manchester and Tyne and Wear. The dressing-room has the range of accents you might expect to hear when catching your connecting train at Leeds.

Yet perhaps the reason this team is held in highest esteem is they have confounded the stereotype of the self-obsessed footballer.

In the months prior to the tournament, tabloid newspapers regaled their readers with tales of some of these players' supposed excesses, yet during the tournament, these players conducted themselves with such distinction that the coverage of the team was overwhelmingly positive.

In future, the team will have stronger challenges to face. There's an argument that they could and should have gone further in this World Cup - that a side with players who've performed in the later stages of the Uefa Champions League should have held onto a one-goal lead, and proceeded to the final against France.

Yet that's a discussion for another time.

For now, England can look back on a team that despite being more diverse than previous squads, still reflected the same ethos that gave some of their predecessors a measure of success - a selflessness, a willingness to put the collective above the individual.

Southgate, too, follows in the proud tradition of fellow England managers such as Graham Taylor - the first person to appoint a black man, Paul Ince, as the country's captain - in promoting the best footballers, regardless of their origin.

Southgate's players may not have expected to be ambassadors for a nation that has endured a turbulent time of late, but it is a role they have performed with aplomb.

And, most crucially, they have become that most important of objects: a mirror in which countless young people can see themselves. Both on and off the field, it is exciting to wonder what they might achieve next.