Premier League: 11 of 20 clubs could have made profits in 2016-17 without fans at games

- Published

- comments

Just two of the Premier League's 20 top-flight clubs recorded a loss in 2017, compared to 18 of the 24 in the Championship

More than half of Premier League clubs could have played in empty stadiums and still made a pre-tax profit in the first season of the current broadcast deal, BBC research has found.

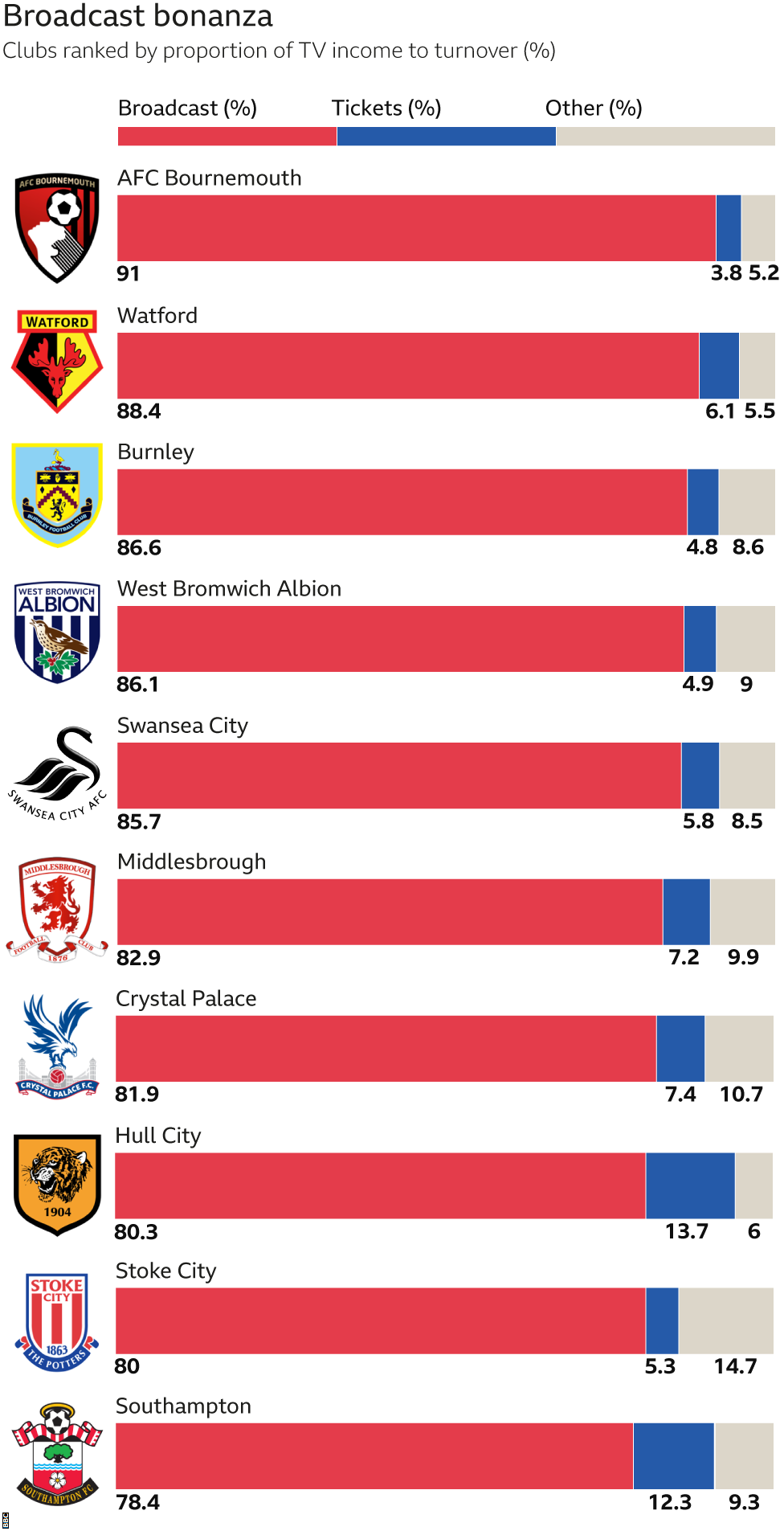

In 2016-17, during which clubs benefited from a record £8.3bn in global TV revenue, matchday income contributed less than 20p in every £1 earned by 18 top-flight outfits.

The number of clubs that would have recorded pre-tax profits even if matchday income was taken away rose from two in 2015-16 to 11 in 2016-17.

Dr Rob Wilson, a sport finance specialist at Sheffield Hallam University, said the previous £3.018bn broadcast deal struck in 2012 signalled a permanent change to top-flight football as a business in England.

"That is when the focus really went toward generating TV money rather than matchday ticket receipts," he told BBC Sport.

"The revenue structures of those clubs are fairly well there to stay now.

"When you get a £120m payout from the Premier League for kicking a ball around, you can play in an empty stadium if you need to.

"From a revenue generation perspective, clubs do not rely anymore on matchday ticket income."

Crystal Palace also would have made a profit of £1.21m - the list of Premier League clubs who could have made a pre-tax profit without matchday income in 2016-17 and the sum of those profits

Bournemouth, with the smallest ground capacity in the Premier League of just 11,450 and who intend to build a bigger stadium, had a turnover of almost £136.5m in 2016-17, with £5.2m from tickets. That is less than 4p in every £1 of its income for the season.

So just how important is it to have fans coming through the turnstiles?

"I'd say they are the most important element," said Football Supporters' Federation chair Malcolm Clarke.

"Players and managers come and go, but we are always there. The reason that they can get lucrative TV deals is because the product shows the crowd, the noise, the away fans and the atmosphere - it is all part of it.

"On one level they don't need the fans because they have got so much money from broadcasters, but at another level they do need fans to keep an attractive product.

"How boring would it be to watch a Premier League game in an empty stadium?"

In a statement, the Premier League said clubs "work hard to fill their stadiums" through a number of ticketing offers, highlighting the £30 cap on away tickets introduced at the start of the 2016-17 season.

"The high-quality football produced by clubs, combined with the commitment of fans, led to an extremely high stadium utilisation of 96% in the Premier League last season, and similar levels have been achieved for many consecutive years," the statement continued.

Following relegation from the Premier League last season, Swansea and West Brom have reduced ticket prices. Their TV incomes have been slashed and replaced by the first instalment of parachute payments.

Swansea will also continue to subsidise travelling members so they do not spend more than £20 for away tickets.

Away tickets are not capped at £30 in the Championship, and Swans chief operating officer Chris Pearlman admits it "may end up costing the club more".

"We would be nothing without the fans," he said. "The reality of the Premier League is that TV revenues have grown so significantly that it is disproportionate to not only every other league but also every other source of income within the Premier League.

"Having said that, a majority of that money is then invested back into the players."

Pearlman added matchdays also generate the "greatest amount" in merchandise sales, with in-stadium signage, local sponsorship deals and programme advertising all heavily dependant on fans attending games.

Crystal Palace chairman Steve Parish said supporters are "the only ones that matter".

"The people that support the team are the people who generate all the interest, the chatter around the club, the intrigue and the interest."

Tottenham, who are set to move into their new 62,062-seat stadium later this season, said they "re-invest everything back into the club and community" and emphasised how "all revenue streams are interrelated".

Hull City vice-chairman Ehab Allam, whose family owns the club and has a difficult relationship with supporters despite overseeing their most successful era, said the fanbase is "crucial".

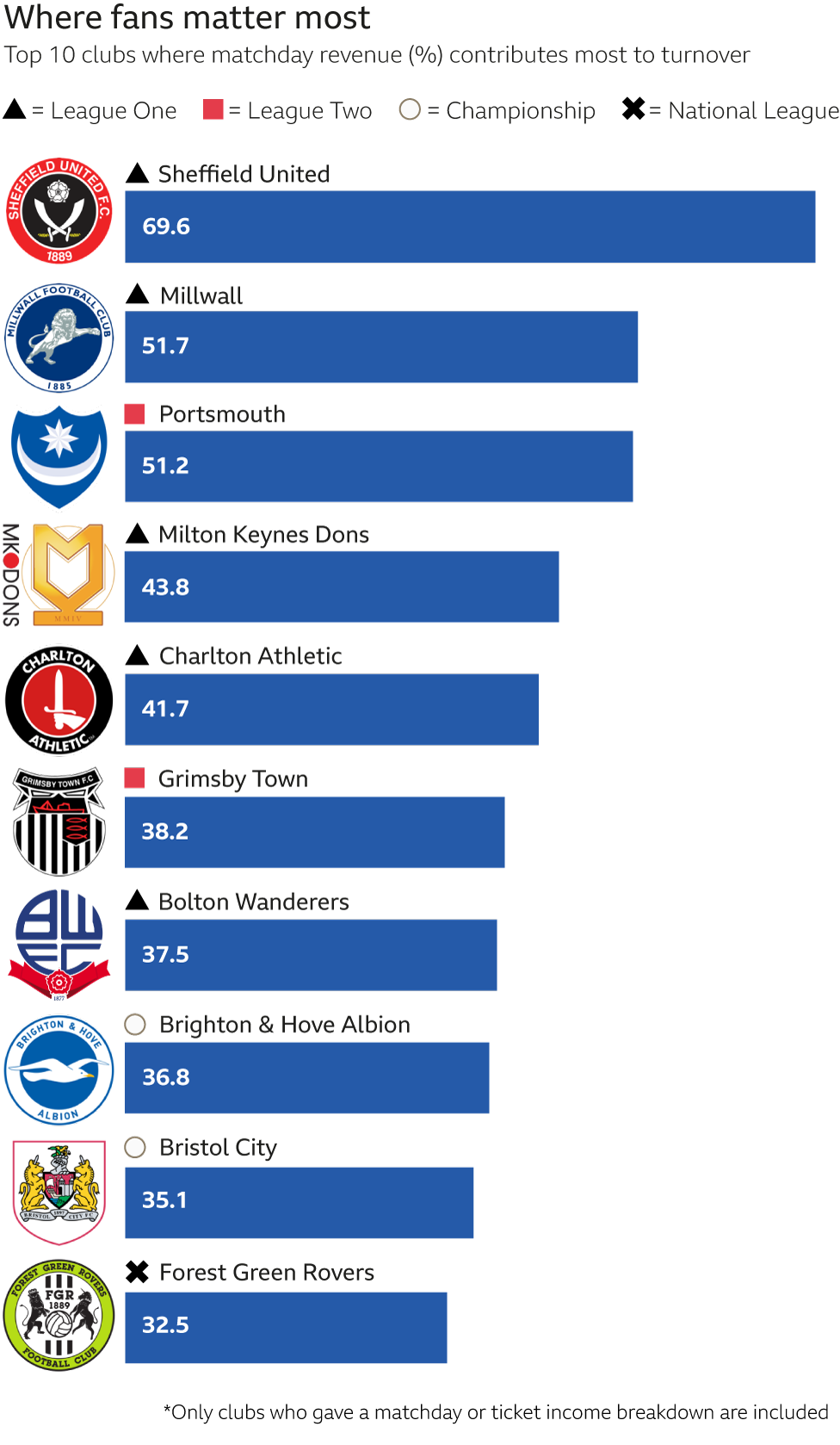

Overall, ticket sales make up about a quarter of the average club's income, according to analysis of the 2016-17 accounts of 61 football clubs from England's top four divisions that provided a figure for ticket sales or similar income.

Some relied on it far more than others.

Leaving aside any loans or funding from owners, and not taking into account whether the club made a profit or a loss, Sheffield United were found to be most reliant on matchday income in three of the four seasons - between 2013-14 and 2016-17 - analysed by BBC Sport and BBC England's data unit.

The Blades made £7.9m from tickets out of a total revenue of £11.4m in their League One title-winning season of 2016-17, which was just under 70p in every £1.

They were one of five clubs from England's third tier to feature in the top 10 list of clubs most reliant on fans, with BBC's Price of Football research in 2017 also showing that the division saw a fall in average matchday and season ticket prices.

What else did BBC's Price of Football find in 2017?

Average season ticket prices across English football's top flight were at their lowest levels since 2013, having fallen for the second consecutive year following a record £8.3bn global TV rights deal signed the previous season.

The Championship's average lowest matchday ticket price had fallen from £22.11 to £20.58. However, the average cost of an away ticket remained the highest in any league in Britain.

In League Two, the average cost of both the cheapest and most expensive season tickets rose.

Clubs, however, need more than just ticket sales, sponsorship and broadcasting revenues to survive.

Accounts show 20 clubs out of 66 spent more on their staff costs - which include everyone from players to office workers - than they made.

For example, Bolton Wanderers - a club that has staved off threats of administration in recent years - spent £12.6m on staffing but made just £8.26m before tax and other costs. That is 153% of its turnover for the year.

Wilson said stadium-going supporters remain "the lifeblood" of many clubs outside the Premier League.

"Clubs are acutely aware that they can get a tangible increase in their revenue by getting more money from matchday receipts, but they can also rely on a pretty solid and loyal fan base," he said.

Clarke, of the FSF, added: "To some extent supporters, especially those of the big old traditional clubs, buy into the fact that without Premier League TV money, tickets may be more expensive to help get them there.

"The lower down the leagues you go, the more ticket prices are important to the club. If they want to succeed they need to afford the players, therefore fans need to pay more.

"We believe that more money should trickle, or in fact waterfall down from the Premier League in a redistribution of that broadcast money. It's in the Premier League's best interests to keep the football pyramid healthy."

In a statement, the Premier League highlighted how lower league clubs, local communities and the wider economy, through the generation of more than £3bn in taxes, "benefit" from the money generated in the top-flight.

"There are many other benefits to having a financially healthy Premier League: significant support and investment is made in communities and schools - including working with 15,000 primary schools in to help them deliver PE, English and Maths - and local sports facilities and the lower leagues," the statement said.

The Premier League also point out that a number of clubs have either built new stadiums or made "extensive" ground developments in recent years.

Kieran Maguire, a football finance expert at the University of Liverpool, said that the importance of ticket sales, while overshadowed by huge broadcast deals, remains significant at the top of the sport.

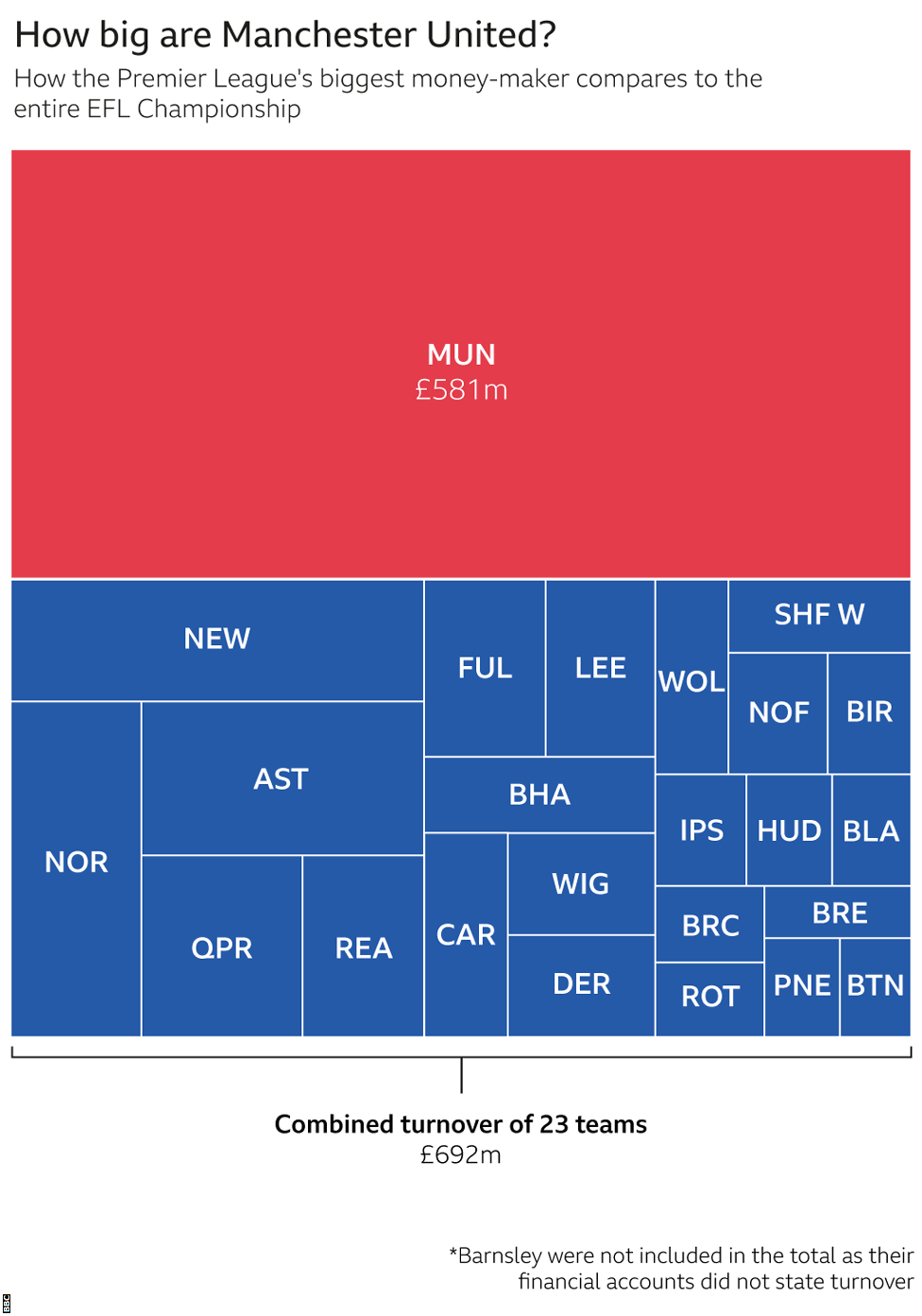

Manchester United, recently ranked as the second most valuable sports franchise in the world by business magazine Forbes,, external brought in more than £111.6m in matchday revenue.

None of the Premier League's top five money makers - Manchester United, Manchester City, Arsenal, Liverpool and Chelsea - would have made a profit without matchday incomes being included.

"Arsenal, Manchester United and Liverpool have each expanded their ground capacity in recent years, and because they do not have benevolent owners in the same vein as Chelsea and Manchester City, matchday income is essential as a means of providing funding for investment in the playing squad in terms of both wages and transfer fees," Maguire said.

"When Liverpool expanded Anfield, a significant proportion of the new seats went to corporate partners and hospitality fans.

"This allows the club to increase its revenue per fan per match, which is an ever more important financial metric given that broadcast income is plateauing and corporate partnership deals are reaching saturation point."

Outside the Premier League, Maguire says relationships with fans are more precious.

"The reliance is different and it often means lower league clubs work harder on building up relationships with fans to ensure they don't become disenfranchised and vote with their feet," he said.

'The only thing we have is to boycott'

Blackpool fans have held frequent protest marches against the club's owners, the Oyston family

At Blackpool, they stay away in droves.

Average attendances at Bloomfield Road dropped from more than 14,200 when they were in the Championship in 2013-14 to 3,456 in 2016-17, a season in which they won promotion from League Two having suffered back-to-back relegations.

In that time, combined season ticket and gate receipts dropped from £2.77m to just £884,565.

The long-running campaign against the club's owners, the Oyston family - described as a "civil war" by Andy Higgins, deputy chair of Blackpool Supporters' Trust - has intensified in recent years after some supporters were sued for comments made online.

Some fans stay away, many march in protests and others even invade the pitch. There is also a 'Not A Penny More' initiative in which fans are encouraged not to spend money in the stadium.

"This is an example that the political side of football and power of the fans is still there," said Higgins.

At Charlton, a section of fans are also boycotting matches in protest against owner Roland Duchatelet.

Charlton and Coventry fans threw thousands of plastic pigs on the pitch in a joint protest that interrupted a League One match at The Valley in 2016

Addicks supporters have done everything from stage sit-ins, storm board meetings, flown to Duchatelet's hometown in Belgium to protest and thrown pig-shaped stress relievers on the pitch to make their point.

"The only thing we have now is to boycott," said Clive Harris, spokesman for a coalition group called Campaign Against Roland Duchatelet (CARD).

In what Harris says has been an "organic" decline, attendances at The Valley have dropped from averages of more than 16,100 in 2013-14, when the club was in the Championship, to 11,162 in the 2016-17 season in League One.

That has coincided with a fall in matchday revenue from £6.315m to £3.176m.

Harris admits going after the club's bottom line "is the ultimate card to play", especially during a time of cutbacks at the club, external which has seen free breakfasts taken away from academy players.

"All Charlton fans want is to feel that they are part of something," he said.

"It almost begs the question of how successful you want a boycott to be. If none of us went, what would happen? It is a dangerous game."

Reporting team: Andrew Aloia, Alex Homer, Steve Marshall, Daniel Wainwright, Pete Sherlock and Paul Bradshaw

- Published13 August 2018