World Cup 2018: Five new things we learned from Fifa's technical study group

- Published

- comments

Harry Kane scores England winner from a corner in their opening game against Tunisia

Despite reaching the semi-finals, England were accused of many things at the 2018 World Cup: Could only score from set-pieces; lacked a creative midfield player; didn't beat a top-class team.

But their approach was not unusual as Gareth Southgate's team reached the last four for the first time since 1990.

In fact, it reflected some of the trends that emerged from Russia, according to Fifa's technical study group, which has produced its analysis of the tournament.

Comprised of Brazil's 1994 World Cup-winning head coach Carlos Alberto Parreira and former Netherlands forward Marco van Basten, the group's report shows why possession might be over-rated, how set-pieces can be successful and why playmakers are vital.

Following their thrilling 3-2 Nations League win over Spain on Monday, perhaps it is further evidence England are on the right track.

Spain and Germany may wish to look away now...

No-one had more possession or passed the ball more at the World Cup than Spain and Germany, yet both traditional powerhouses went out early in the tournament.

Winners France had an average of 48% possession, less than Australia, Tunisia and Morocco, and made an average of 460 passes per game, almost half of Spain's 804.

But when Les Bleus did pass it, they reached their target 70% of the time.

In other words, less was more, and when they had the ball, they made the most of it.

Their average number of final-third entries (joint 17th), penalty area entries (joint 18th) and crosses (joint 28th) ranked poorly.

And yet, only Belgium scored more goals than Didier Deschamps' team. Only Russia took fewer shots to score a goal (4.5) than France's six. Germany needed 36.

Efficiency and incisiveness counted. It was a feature of the tournament as a whole.

Former England midfielder and manager Glenn Hoddle likened England's approach at corners to the 'Love Train' - a disco classic from the 1970s by The O'Jays.

Harry Maguire, John Stones and Harry Kane lined up behind one another before pouncing - and it was a technique that worked.

No-one scored more set-play goals than England's nine in Russia, while their four from corners was another World Cup high.

Overall, there was an increase from this route too. One in every 29 corners led to a goal, whereas the figure was one in 61 at South Africa 2010 and one in 36 at Brazil 2014.

But that's not all England were. As Van Basten said: "They took initiative playing out from the back."

Efficiency was also a key theme in terms of running. After a long season and with lots of matches in a short space of time, energy was at a premium.

As former Croatia and AC Milan midfielder Zvonimir Boban, now a Fifa deputy secretary general, said: "Pressing was far less prevalent than previously. At a tournament of the magnitude of the World Cup, energy levels and mental sharpness need to be conserved as far as possible."

Only four teams covered less distance than France per game - Argentina, Nigeria, Mexico and Panama.

France's average of 101km per game lagged well behind the 113km covered by leading nation Serbia, who went out at the group stage.

England were the seventh leading nation in the category, having covered an average of 107km per game.

When it comes to sprinting, defined by a speed of more than 25km/h, France ranked higher, which might be obvious with pacey forward Kylian Mbappe in their side. Deschamps' team were 17th for the average distance covered at more than 25km/h at 2,007 metres per game.

Interestingly, Spain were the second worst team behind Sweden with only 1,588 metres covered by sprints per game.

The World Cup in Russia was a tournament of goals. There were 169, only two fewer than the record for a 32-team World Cup, which was set at France 1998 and equalled at Brazil 2014.

Only one match out of 64 ended goalless (Denmark v France), compared to five in Brazil and seven at South Africa 2010. As Carlos Alberto Parreira said: "There was an attacking mentality."

In addition to set-pieces, goals from outside the penalty area also contributed to this, and the improvement was dramatic.

The average strike rate was a goal per 29 long-range attempts in Russia, compared to one in 42 at Brazil 2014.

The study group says there has been a 32% drop in shots from outside the penalty area since South Africa 2010 because of "tight, compact defending".

Only hosts Russia were more clinical than France's 9.5 shots per goal from outside the area. Croatia had 54 shots for one goal from the same range, while Germany's 36 shots from outside the area brought no reward.

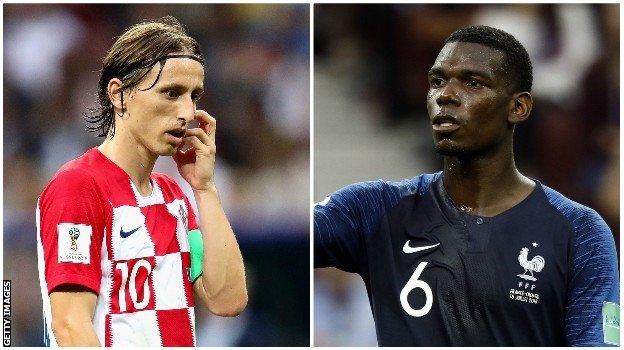

Luka Modric earned the Golden Ball for his performances at the World Cup, while France's Paul Pogba scored in the 4-2 win over Modric's Croatia in the final

The importance of playmakers

The report says there was a lack of playmakers in the 2018 World Cup, and cites how important they are in successful teams.

Step forward Golden Ball winner Luka Modric and Paul Pogba, who helped Croatia and France respectively reach the final.

The report also cites how Andrea Pirlo was instrumental in Italy's 2006 World Cup win, how Andres Iniesta and Xavi pulled the strings in Spain's 2010 success and how Bastian Schweinsteiger was Germany's chief orchestrator four years ago in Brazil.

Maybe that was the difference between the four teams which made the semi-finals. England were described by the report as "very solid in defence with two players who linked up well in attack" while Belgium were "very technically gifted and incredibly versatile".

Tactical flexibility and a clear plan of action were noted as being key components of success in Russia, yet a coach can only do so much on the pitch.

Having a playmaker to "speed up or slow down the tempo, switch play, create and make things happen" as Parreira notes, seemed to provide the most telling difference of all.