The plane crash that killed Serie A's champions and their English coach

- Published

- comments

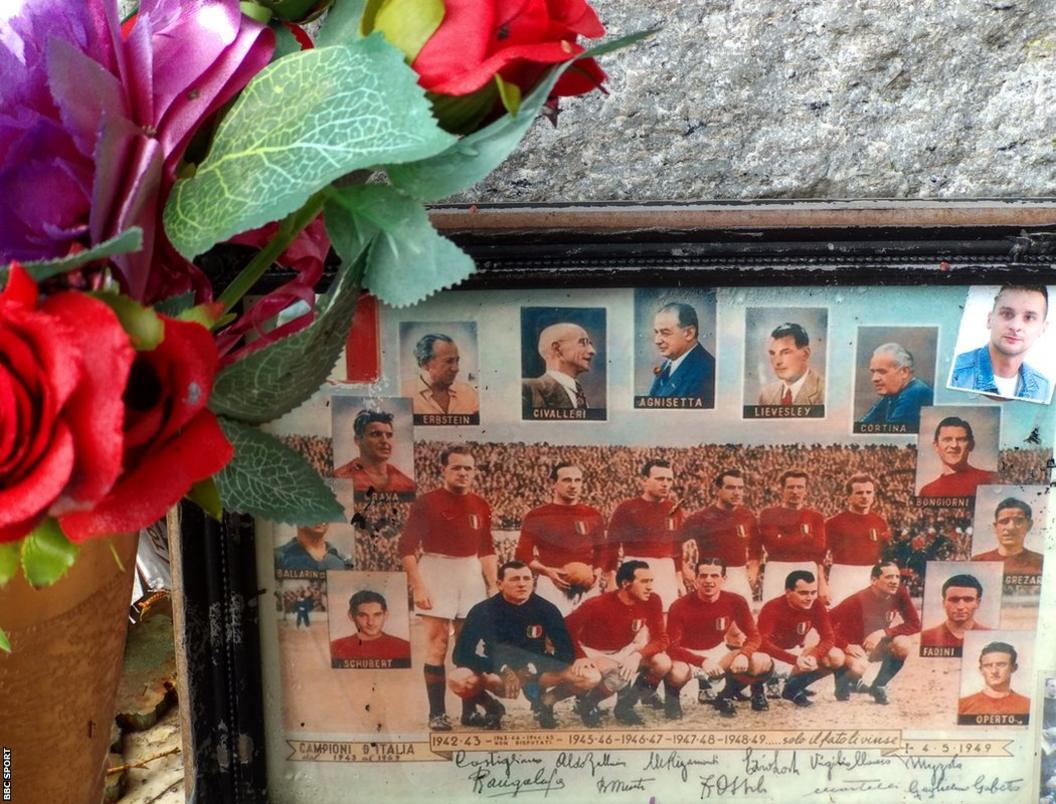

Leslie Lievesley (back row, far left) became a coach at Torino in 1947

Bill Lievesley had just got home from school when his mum came in and told him: "People are saying there's been a plane crash."

Close by on the outskirts of Turin, the wreckage of an aeroplane lay smouldering on the Superga hill, 700 metres up behind the giant basilica that overlooks the city.

Going through the suitcases and bodies, searchers eventually identified the victims and began to realise that among the 31 dead were Serie A's all-conquering champions, Il Grande Torino.

It was 4 May 1949 and Torino were set to win a fifth consecutive league title. With four matches of the season remaining, the team had flown out to play a testimonial match for a Benfica player in Lisbon.

On the way back, almost the entire squad was killed, including their Hungarian-Jewish manager who had escaped from the Nazis and their English coach Leslie Lievesley, a former Manchester United full-back who incredibly had survived three previous air crashes. His son Bill was about to turn 11.

On that late afternoon, news quickly spread throughout the north Italian city. By evening it had reached Sauro Toma, a defender who had not travelled with his team-mates because of injury. Scores of emotionally overwhelmed fans mobbed him in the street. Before his death in 2018, aged 92, he said he lived as someone "condemned to survive, while my brothers perished".

The plane had collided with the back of the basilica wall, amid thick fog. Later it was concluded malfunctioning equipment must have led the pilot to believe he was well clear of the building, realising only when it was too late.

Two days after the crash, half a million people lined the streets as the funerals were held. Torino were awarded the Serie A title, at the request of their rivals. Only fate could beat them, it was said. The team passed into legend not as the Invincibles but the Immortals.

The next season each top-flight club was asked to donate a player to Torino, to help them rebuild. The 1949-50 title was won by Juventus, as Torino finished sixth. They have won the league only once since, in 1975-76, the seventh title in the club's history. This season, city rivals Juve won their eighth in a row, and 35th of all time.

The Superga disaster is central to Torino's identity, and its legacy is not forgotten. Every year thousands congregate at the site where the plane came down. This year will be the 70th anniversary and Bill Lievesley will be among those present.

He first went back for the 60th anniversary, in 2009. He can't really say why he hadn't been before. "I'd been saying it so long, 'now I'm going to do it'. I really owed it to my father to go, and to do it properly," he tells BBC Sport.

On that first trip back, 10 years ago, Bill walked all the way up to Superga and back down to the city again, twice, in two days. It's about 10km from Turin's centre, up twisting roads that lead to the summit finish in the Milan-Torino cycling race. He stripped the soles of his shoes.

We meet where he now lives, in England. The day grows dark as we talk in the comfort of his living room, drinking coffee. Bill is 80 and radiates warmth on a bitterly cold afternoon in south Yorkshire, looking back on a time when Turin was home.

Along the hallway and up the stairs hangs his "gallery of rogues". There are photos of his dad, Leslie, as a Doncaster Rovers player and in a Manchester United team photo, alongside frames of his grandad Joe, goalkeeper for Sheffield United and Arsenal.

Leslie Lievesley moved his wife and young son to north Italy in 1947, when he left his first job as a coach with Dutch side Heracles Almelo to join Torino, having turned down an offer from Marseille.

The English coach was joining an already successful side. Torino became the first Italian team to win the league and cup double in 1943, the final season before Serie A was halted for two years during World War Two. They still hold three remarkable Italian top-flight records.

In 1947-48, Torino scored 125 goals in their 40 matches, finishing with a record goal difference of +92 on their way their fourth title in as many seasons. By the time of the Superga disaster they had not lost at home in more than six years, while their 10-0 victory over Alessandria in May 1948 remains the biggest in Serie A history.

This golden age for the club owed much to its president, Ferruccio Novo, who had lovingly signed up some of the country's best players, including Valentino Mazzola, Torino's star who became Italy's captain. Novo was devastated by the disaster. Mazzola had named one of his sons after him.

Novo did not travel on the fateful journey because of a bout of flu. Having failed in the perhaps impossible task of rebuilding the team after the crash, he resigned as Torino president in 1953, three years after leading Italy to the World Cup finals. The Azzurri travelled to Brazil by boat rather than by plane.

The other major influential figure in the club's success was Erno Egri Erbstein, the team's Hungarian manager who had been forced to return to his homeland following the 1938 anti-Semitic law that stripped Jews of their Italian citizenship under Benito Mussolini.

Erbstien escaped from a labour camp in Nazi-occupied Budapest, as is detailed in the book Erbstein: The Triumph and Tragedy of Football's Forgotten Pioneer, external by Dominic Bliss. He would return to Torino after the war and continue to win football matches according to his attacking ideals, with help from his English coach.

'Dad probably thought he could beat Hitler single-handed'

Born in 1911, Leslie Lievesley got into coaching after his playing career was cut short by the war. He was at Crystal Palace, and Bill was a baby in Croydon, when in 1939 he signed up to join the Royal Air Force. He became a parachute dispatch officer, often involved in missions to drop soldiers, and sometimes spies, behind enemy lines.

On one such sortie, having been forced to return to base before completing their drop, his plane was shot down over Middle Wallop, just north of Southampton, by American anti-aircraft guns. Friendly fire. Everybody on board was killed, apart from Leslie, who walked out of it. "He was hard as nails," Bill says of his dad. "He probably thought he could beat Hitler single-handed."

There was a second crash in the war - although Bill can't recall the details. The third that Lievesley survived came in 1948 when, travelling with the Torino youth team, the plane's brakes malfunctioned on landing at Turin airport. Disaster was averted because the wing clipped a hangar and slowed the aircraft before it could collide with the terminal building.

That same year, England travelled to Turin to play Italy. Seven of the Torino team lined up against an English side led by goalkeeper and captain Frank Swift, who, as a journalist, would perish in the 1958 Munich air disaster. Stanley Matthews played out wide and Tom Finney scored twice in a 4-0 win.

Lievesley was by that time also coaching Italy - it was essentially the Torino team after all, in one match all 10 outfield players came from the club. Bill remembers the heavy defeat by England did his father's reputation little damage - if anything, it only increased the desire to learn from the inventors of the game.

Lievesley seemed to always enjoy support from those who mattered most, the players. According to Bill, it was the Torino players who asked for him to be promoted to the first team, having observed his good work with the youth side.

From marble floors to a colliery house and an outside toilet

As a child, Bill would often be taken along to his father's training sessions - "when my mother had had enough of me," he says. He might watch his dad work, or kick a ball about himself with the other kids hanging around Torino's old Filadelfia stadium. It closed in 1963, and for years it lay abandoned. In May 2017 it opened once more and is now back in use as a training ground.

Bill says he was never much of a footballer himself. Cycling was more his thing - twice he competed in the Tour of Britain. But there have been times when he has wondered, what if? What if his dad had chosen to take up the job at Marseille instead, for example. What if his mother had stayed in Italy?

"There were some people who thought she ought not to leave, but she decided she should bring my dad back home, to be buried with his father and brothers," he says.

"I wish we had stayed out there, quite frankly, but she did what she thought was best at the time.

"Coming back to England was not particularly easy. At first we lived with my grandmother in Rossington, not far from Doncaster. It wasn't like our apartment in Turin with marble floors, it was a colliery house.

"In Italy my mum and dad had something of a celebrity lifestyle. Gianni Agnelli, the future head of Fiat, was a big friend of my father's. He'd always be offering him a car but he wouldn't take one, he said they made people lazy. All the players would always cycle around the city.

"We stayed with my grandmother for about a year. It was a strange time for me, like I was walking around in a dream. I think I was just going through the day to day really. You cut yourself off a bit, don't you?

"They put me in for the 11-plus, which I obviously failed miserably. I knew all about Garibaldi but not very much about pounds, shillings and pence. It was all foreign to me.

"There was very little room in the house, no bath, no electricity, the toilet was outside, but I got used to it. Then my mother got some compensation money - either from the airline or the club, I'm not sure - and bought a house in Doncaster.

"I was very dependent on my mother, I really could have done with my father being there. I only knew him for those few years after the war. That's the sad thing of it."

During the brief hours I visited Superga, having arrived by car and not on foot, the air was crisp and the sun's light especially bright as it reflected back off the spectacular snow-covered Alps in the distance. It was difficult to imagine the terrible sights and sounds of that disastrous day, when Torino's small three-engine Fiat passenger plane was immediately destroyed in a direct impact with the holy building that stands guard over the stunning valley below.

There is a memorial monument against the back wall where the plane came down. Football fans from all over the world have been coming here for years to pay their respects and have left scarves of many different colours. There used to be a museum within the basilica itself, before it was forced to move, and it is now housed in a much larger space in Grugliasco, a suburb of Turin.

Strangely, the club itself offers no official support, funding or encouragement to the museum. In fact scores of items, relics of Torino's golden age, were discarded and left abandoned under a previous ownership. They now sit proudly as exhibits in the museum run by dozens of dedicated volunteers.

They have helped keep the memory of Il Grande Torino alive - not just for one day in May.

The view from the Superga basilica down onto Turin below

The aftermath of the Superga air disaster

Thousands of people come to pay their respects to Il Grande Torino

Fans from all over the world have left their own personal tributes to the victims