How is football tackling racism on social media?

- Published

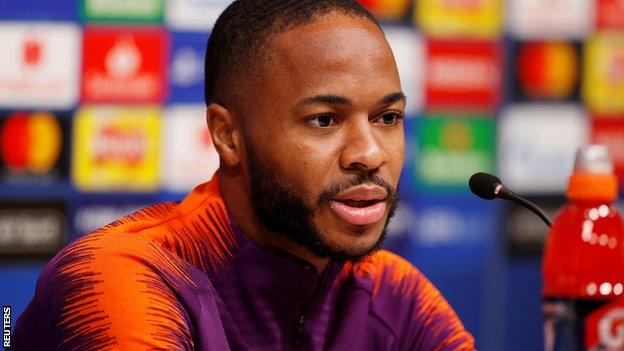

Raheem Sterling has been a leading voice in the fight against racism

Abuse of footballers, and in particular racist abuse, has provided an unwelcome theme throughout this season.

Barely a week - often a day - goes by at the moment without a story about a footballer being racially abused on social media.

Watford captain Troy Deeney disabled comments on Instagram after alleged racial abuse aimed at him and his family, while on Wednesday Manchester United said they "will take the strongest possible action" after defender Ashley Young was racially abused on Twitter.

So what are clubs, the authorities and players themselves doing in response?

Clubs - a need to protect players

"A player's transfer market value can be driven by their social media presence, so if the clubs are willing to profit from that, then they also need to protect them."

Those are the words of Ben Wright, head of sport at communications agency Cicero, who work with a number of clubs and players, including those in the Premier League and Spain's La Liga, around aspects of their social media use.

One of Cicero's main roles is to produce reports for clients on a player or potential transfer target's character by analysing their online presence, while the agency also offers advice and guidance on how to deal with abuse on social media.

"Some clubs are great, some not so good, but generally they are all moving in the right direction and realise they have this duty of care," Wright told BBC Sport.

"Social media in its most basic form is a direct contact channel between players and fans, which you previously only got at the stadium in matches."

Chelsea prevented three people from entering the stadium for last week's Europa League quarter-final at Slavia Prague after a video was circulated on social media of a group of fans singing an abusive song about Liverpool forward Mohamed Salah.

The club said it will "take the strongest possible action" when there is evidence of Chelsea season-ticket holders or members involved in such behaviour, calling it "an embarrassment", while the Metropolitan Police said it would seek to apply for civil football banning orders.

When Wigan defender Nathan Byrne received racist abuse on Twitter following a draw with Bristol City on 6 April, the Championship club reported it as a hate crime.

A man was subsequently arrested by police on suspicion of a racially aggravated public order offence and malicious communications, after handing himself in at a police station in Blackpool.

Does outing trolls work?

Wright says it is a common misconception that players' social media profiles are managed, stating that his clients are in control of their own output.

He adds that Cicero will never tell players what they should or should not do in response to abuse, as it affects each person differently.

Troy Deeney disabled comments on Instagram after the alleged abuse aimed at him and his family following the Hornets' FA Cup semi-final win over Wolves on 7 April.

Deeney said he did so to "prevent young people" from seeing the comments and to not "expose people I care about to these small-minded people". He has enabled comments on posts since then.

His Watford team-mate Christian Kabasele thanked fans, external from various clubs for their support since reporting the racist abuse he received.

"Switching off comments is the social media equivalent of playing behind closed doors," said Wright. "The majority of fans are not racist or bigots.

"Troy Deeney has hugely fierce ties with Watford and it's a shame he felt he couldn't share those with fans [because of the abuse he received]," said Wright.

"He engages with fans a lot, and had to forego all engagement which is 99% positive, but equally he is the one that has to deal with the abuse."

Wright says that abuse affects players more when it is also aimed at their families, as was the case with Deeney.

"Their families don't have access to the counselling, support and training the players have, so it hits them even harder and then it hits the players harder," he said.

Crystal Palace winger Wilfried Zaha has adopted a different approach in dealing with the racist trolls he has encountered on Twitter, most recently after being awarded a penalty that led to the Eagles' winning goal against Newcastle on 6 April.

The 26-year-old says he laughs at the abuse, and has been retweeting the perpetrators in a bid to catch the attention of the authorities.

"I would say that gives the trolls the notoriety they want," countered Wright. "It's great to flag it up if they are going to be punished, but if not they are getting away with it."

Should social media platforms do more?

Cicero says it is widely accepted that social media companies are "too slow and not good enough at defining something as hateful or abusive content".

It comes as the government issued a white paper that proposes new measures to regulate internet companies who do not adequately protect their users.

Home secretary Sajid Javid said the government could not "allow the leaders of some of the tech companies to simply look the other way and deny their share of responsibility".

A Twitter spokesperson said "abuse and harassment, no matter who the victim, have no place" on its platform, adding that it uses "proprietary-built internal technology to proactively find abusive content".

But anti-discrimination charity Kick It Out says those measures are "evidently" not working and released a statement, external on 9 April "calling on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook to take decisive action to combat the abuse faced by footballers on their platforms".

A recent Press Association study highlighted that abusive tweets aimed at Premier League footballers could be found on Twitter up to five years after being posted.

"Twitter says abuse and harassment has 'no place' on its site, but it is obvious that there really is a place for it there and in our view the problem is getting worse," a Kick It Out spokesperson said.

"Footballers, like anyone in society, are entitled to go about their work without being abused, intimidated or trolled."

Football's governing bodies have been speaking out about racism within the sport recently. Last week, Fifa president Gianni Infantino urged football bodies, leagues and clubs to "apply harsh sanctions" and a "zero-tolerance approach" to racism.

Uefa president Aleksander Ceferin said he will ask referees to be "brave" and stop matches where there is racial abuse from fans.

The Football Association encourages people to report an incident of discrimination in football, external - whether it took place online or at a grassroots, non-league or professional game - by filling in an online form. FA chairman Greg Clarke has said the governing body must take a default position of believing those reporting racism or discrimination.

In Scotland, representatives from league clubs, the Scottish Football Association, Scottish Professional Football League and the Scottish Government attended an anti-racism summit in February.

A generation of socially aware players

Manchester City forward Raheem Sterling has led the way in speaking out against racist abuse, with the 24-year-old described as a "trailblazer" as he was named sportsman of the year at the 2019 British Ethnic Diversity Sports Awards.

He was among a number of high-profile footballers to use social media to condemn comments from Juventus defender Leonardo Bonucci that suggested team-mate Moise Kean was partly to blame for the racist abuse he received from Cagliari fans.

And Wright says the England international is part of a new generation of socially aware players who now are trusted by clubs to speak openly and use their high-profile positions to confront issues in society.

"Gareth Southgate's England team are probably the extreme example but there is a new generation of socially aware players," he added.

"Raheem Sterling is talking about racism, Chris Smalling is talking about education for deprived kids, Danny Rose has been very vocal on racism and depression.

"Players are much more aware and are seen much more as role models."