Trans-Dniester: The disputed 'smuggler's haven' ruled by Moldovan 'football kings'

- Published

- comments

"Ask not what Trans-Dniester can do for you - ask what you can do for Trans-Dniester."

We're driving down Andriy Smolensky's favourite street. It's the only one in Tiraspol that doesn't cause his Land Rover to bounce and rattle over potholes and broken concrete.

"They've used a new technology to make it like this," he says, almost proudly. "I could drive up and down it all day."

The tiny de facto republic of Trans-Dniester - sometimes known as Transnistria - is a place frozen in time.

In its capital Tiraspol, the hammer and sickle motif of the former USSR blares proudly from billboards and government buildings. A huge statue of Lenin watches on from a plinth outside parliament, a mark of the pride and nostalgia the city feels for its Soviet past.

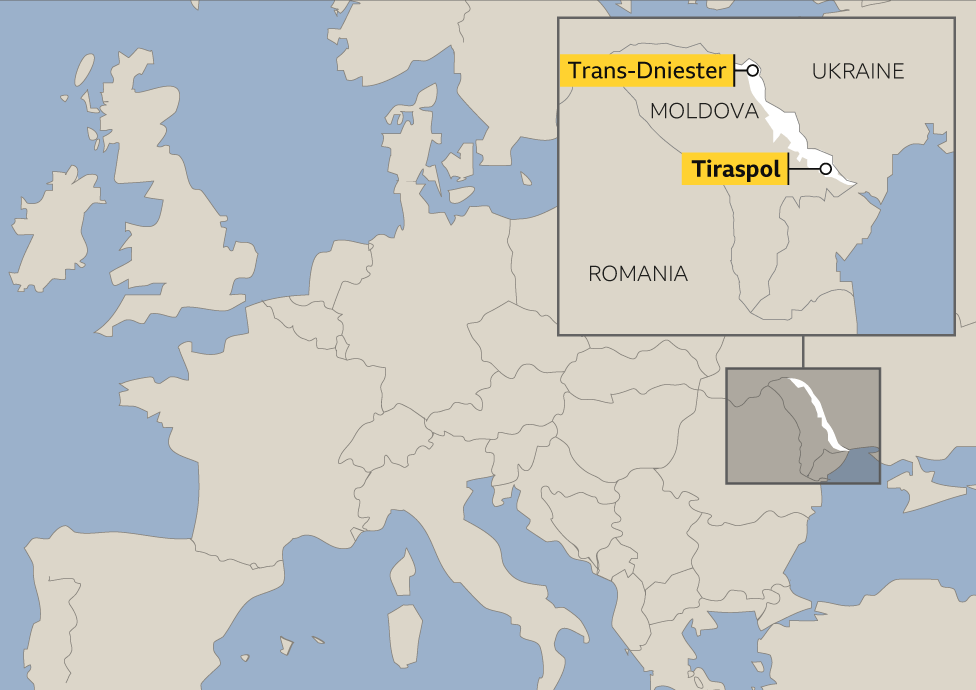

In international law, Trans-Dniester, a thin sliver of land on the border with Ukraine, belongs to the Republic of Moldova, a country formed in 1991 as the Soviet Union was collapsing.

In 1992, Russian-backed forces fought a separatist war here. When it was over, close to a thousand people had been killed, and the land east of Moldova's Dniester river had seceded to form a self-declared new state that remains unrecognised by the international community.

Trans-Dniester takes its 'independence' from Moldova seriously. It uses its own currency, the Trans-Dniestrian rouble, which cannot be obtained or exchanged anywhere else in the world, and which sits outside of the international banking system. In Tiraspol, phone signals from Moldova don't register, despite the 'border' being only 20km away.

The territory has a reputation for corruption, organised crime and smuggling. American foreign policy think-tank the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace described it as "a haven for smugglers".

Millions of dollars of contraband are believed to have moved across its border with Ukraine in recent years. Yet in Tiraspol, buildings are crumbling and the roads are cracked. The capital is a picture painted in Soviet grey.

Smolensky used to work here as a broadcaster, transmitting Russian-funded German-language programmes to Europe and the United States that "spread the message" of what Trans-Dniester is trying to achieve.

Before that, he was employed by the territory's biggest private firm, the Sheriff Company. He worked on immigration papers for overseas signings at the company's football club, FC Sheriff Tiraspol.

FC Sheriff have played in Moldova's football league since 1999. They are kings ruling over a peasant land. The Sheriff Company annual turnover is almost double the state budget, and it funds the club directly from its vast wealth reserves. The rest of Moldovan football is impoverished by comparison.

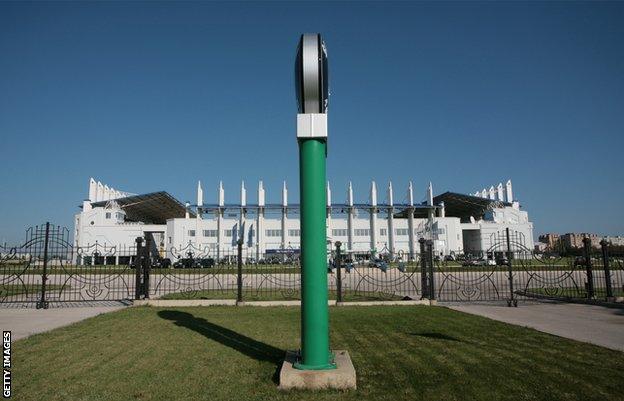

While the rest of the top division play on sports pitches rented from municipal authorities, Sheriff's home is a specially constructed $200m (£154m) arena on the outskirts of Tiraspol. They have won 17 out of the 19 league titles they have contested.

Sheriff Tiraspol met Tottenham in the Europa League group stage of 2013-14, losing 2-0 at home and 2-1 in London

The name Sheriff is synonymous with power in Trans-Dniester. The Sheriff Company was founded in 1993, ostensibly as a charity with the aim of providing financial assistance to veterans of the local state police in the immediate post-Soviet era.

Today, it dominates everything from food retail to banking, from the media to politics. While nominally a private business concern, it indirectly holds 35 of the 43 seats in parliament through its political party, Obnovlenie - Renewal.

There is no formal connection between the Trans-Dniestrian government and FC Sheriff, but its position of political and economic strength is steadfastly secure.

However, Petr Lulenov a member of the Trans-Dniestrian Football Federation, says the club does not have everything easy.

"It was the business model of the club to sign foreign players from South America and from Africa, add to their value and then sell them to Russian clubs," says Lulenov.

"But because the domestic league is so weak and there is little competition for Sheriff, that policy no longer works.

"It was also hoped that teams from Russia and Ukraine would come and use the club's facilities and that that would help create big football rivalries, but it isn't the way it's turned out. The football club is run at a massive loss."

Speaking to ordinary people on either side of the Dniester river, the view seems to be that the partition of Moldova serves nobody but the political elite.

That is a position echoed by authorities in Ukraine. Yulia Marushevska, head of the Odessa regional customs division, said in 2016: "[The situation] is suitable for contrabandists, and for high-ranking officials in Chisinau and Kiev.

"This is a matter of political will, both for the Ukrainian authorities and for the Moldovan authorities."

Since the crisis in Ukraine that began in 2014, there has been a tightening of border controls. In July 2017, a customs post, jointly operated by Ukrainian and Moldovan authorities, was set up at the border village of Pervomaisc-Kuchurgan.

The European Observatory on Illicit Trade (Eurobsit) estimates that 70% of the illegal trade passing through Trans-Dniester had previously entered and exited at this crossing, on its way to and from the Ukrainian city of Odessa.

Meanwhile, a 2014 free-trade agreement between Moldova and the European Union included Trans-Dniestrian businesses in its scope, and exports have since swung dramatically away from Russia and towards Moldova and the West.

In a referendum in September 2006, not recognised by Moldova or the wider international community, Trans-Dniester backed a plan eventually to join Russia

It seems despite 29 years of deadlock, there are signs of greater co-operation.

"This conflict is not totally frozen, rather it is a conflict of frozen solutions," says Octavian Ticu, a historian and former minister in the Moldovan government.

"Moldovans have interests with Trans-Dniestrians, they deal well together in business."

Outside of the capital, football does what it can to soothe the horrors the past.

In the town of Bendery, just a few kilometres inside the Moldovan border but under Trans-Dniestrian control, a military roadblock manned by khaki-clad soldiers beckons cars to a crawl as they flow in and out of town.

A mounted tank points its barrel triumphantly at the overcast sky. Along one side Cyrillic lettering bears a call to arms: За родину! - For the homeland!

Situated on the banks of the Dniester, this is a city of the crossfire.

Alexandru Guzun was due to play for Bendery club FC Tighina against FC Constuctorul the day a simmering conflict broke out into war. The date was 2 March 1992.

"Can you imagine the shock of arriving in a city you know well and seeing bombs exploding in the streets?" he says.

Guzun was due to meet with his team-mates at a hotel before travelling together to the club's Dynamo Stadium home ground. That isn't the way it worked out.

"The hotel was right on the river. Because of where it is located, with Tiraspol only a few kilometres one way and the Moldovan soldiers coming from the other, we were physically in the middle of the fighting."

Once inside the hotel, it quickly became clear that there was no way out. With bombs and shells exploding around them, Guzun and his team-mates took the only route open to them - downwards.

"We took everything we could down to the basement. Everything we needed to live. We would take it in turns to go up to the first floor hotel restaurant to get supplies and take them back down for everyone. We were trapped there for three days," he said.

"On the second day of the siege, some pacifists who were on neither the Moldovan nor the Trans-Dniestrian side, came to the hotel. They erected a white flag from the top floor. These guys lived underground with us.

"We found out since, that an agreement was reached between the two parties for a ceasefire to allow people inside the hotel to escape. I don't believe that could have happened without the guys who came with the white flag.

"But we still had to make it from the hotel over the bridge. Just because a ceasefire has been agreed, it doesn't mean no one will shoot at you. Nobody would have investigated. The bridge was full of bullet holes."

Guzun left FC Tighina at the end of that season to move to Ukraine. Most of his team-mates followed. It took years for the city to recover from the distress suffered in the first half of 1992. A ceasefire in July that year brought the conflict to an end.

Back in Tiraspol, FC Sheriff's power is so entrenched that they are unlikely to be surpassed by their impoverished rivals in the Moldovan league any time soon.

At the start of April, the 17-time league champions lost 1-0 at home to their closest challengers, FC Milsami from the city of Orhei, and yet they are still fully expected to win an 18th title.

A stale, uninteresting dominance prevails. In an indifferent, half-full stadium, the 40 or so visiting fans confined behind a fence in one corner made more noise than the rest of the stadium combined.

"The football club will never collapse," says Lulenov. Instead, it limps on, a privileged but sickly prince among paupers. And still the roads are cracked.

"Peace and prosperity, that's all we want," says Smolensky, swerving to avoid another gaping hole in the ground.

"When you have that, everything else takes care of itself."

A banner displayed as part of 'independence' celebrations in 2015 reads: 'Thank you Russia for peace on the Dniester'

A sign in Trans-Dniester reads: 'We remember: We are not Moldova!'

A majority of Trans-Dniester's population are Russian-speakers

Sheriff 's stadium in Tiraspol cost around $200m (£154m) to build