Cost of the Game 2019-20: Is a Netflix model the future for Scotland?

- Published

Every month, Netflix might take a few pounds from your bank account. Amazon may well help themselves to a similar amount. Then there is Spotify, Apple and others like them potentially having a nibble, too.

What if your football club of choice did the same? In return you'd get a season ticket. Priority for away games. Maybe discounts in the club shop. Perhaps the chance of your kid being a mascot. Or even your name on a brick. Furthermore, you'd have the warm glow from being a minor benefactor in your club.

Does that sound more appealing than parting with several hundred pounds at the start of each season to secure your seat for games that you might not be able to go to, in a ground where availability is rarely an issue?

As part of the Cost of the Game series, BBC Scotland looks at whether the traditional season ticket is still fit for purpose, whether subscription schemes are viable, and how they work in other countries.

Are season tickets fit for purpose?

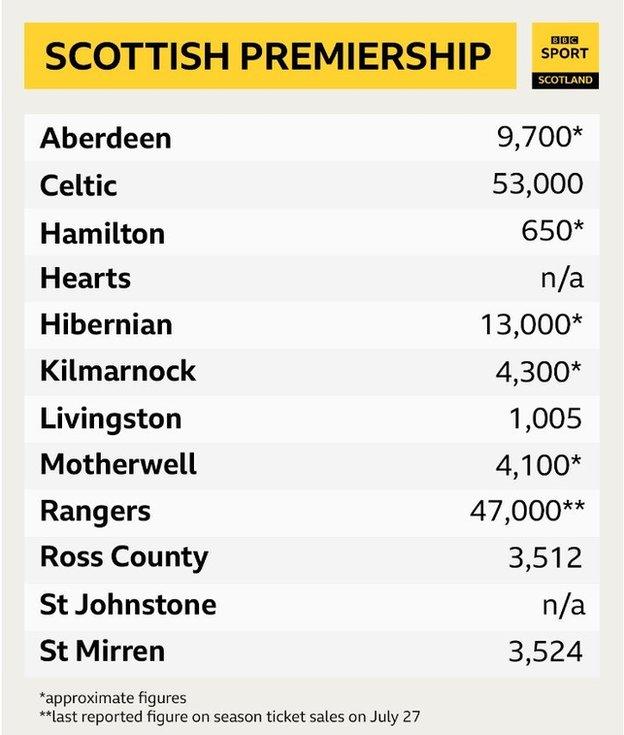

Scottish Premiership clubs have sold somewhere in the region of 150,000 season tickets between them this season, and the 2019 Deloitte Report estimated around half of all top-flight revenues come from ticket sales.

Clearly, then, there is still an appetite for them despite changes in society and in the parameters of the working week shifting vastly over the decades.

Obviously, at certain clubs, fans get them in part so they can guarantee entry to particular games. But many buy out of habit, others obligation, and some just want to make sure they are sitting beside friends or family in a seat they have become used to. Studies suggest that any fan with more than 75% usage over a three-year period will usually keep renewing.

Season tickets per Premiership club this season

"A lot of supporters see season tickets as contribution to the club rather than a purchase," says Colin Millar, operations manager at Hibernian, who have sold more than ever in the last two terms. "Price is obviously a factor, as is success to a degree, but the motivations for buying them are more complicated than that and also include intangible stuff like hope and trust."

The concept of value does remain key, though. Dundee United have shown an upturn in season ticket sales (circa 4,500) for the first time in five seasons despite being consigned for a fourth campaign in the Championship - something that the club attribute in part to significantly sprucing up Tannadice.

"It's about putting value back into them," says managing director Mal Brannigan. "If fans renewed early, it was the same price as last season. Before, if you missed three or four games, it wasn't worth having one, this year, that's gone up to six or seven by us increasing the matchday price."

Would a subscription model work?

So let's take the two clubs already mentioned. The cheapest season ticket at Hibs this term is £385, while it costs £279 at United.

What if rather than charging that money up front in May, June or July, it was split across the calendar year? That would mean a monthly payment of £32 to Hibs and £23 to United. Granted, the latter already have their own scheme that allows fans to pay in instalments, but it doesn't split the cost as widely.

"Technology is the key to it all, but I think an annual pass that fans can buy any time during year is a very good idea," says Brannigan. "It's certainly do-able at some point if it's what the supporters want."

Subscription models also offer fans greater flexibility. What about those who can make only one or two games a season? Or those who go to more, but not enough to justify buying a season ticket?

Several of Scotland's bigger clubs have launched membership schemes in recent times to serve those supporters who want a bond beyond just going to the odd game. Perks such as priority tickets, discounts on gate prices and money-off vouchers for merchandise are all offered, with some such as AberDNA stipulating that any money raised goes only to the first-team budget.

Granted, such subscriptions are not entirely without controversy - the issue of auto-renewal might take some getting used to - but people are now used to paying monthly direct debits for services.

What is preventing their use?

The simple answer is cashflow. Scottish clubs have built their business models around getting an influx of cash in the early summer to enable them to pay their players throughout the close season in the absence of fortnightly gate receipts.

Brannigan, however, insists he would be "relaxed" about that changing. "Sure, there would be a bump in first 12-to-24 months as we all get used to it, but the money comes in whenever and you run your business around it," says the United managing director.

At Hibs, Millar talks about the desire to maximise season tickets for as long as possible, given that customer base is established, and also points out another potential problem.

"Clubs might be hesitant in that instead of increasing frequency, a subscription model tips things the other way and those who currently commit to a season ticket decide not to bother."

And might fans whose club are suffering a wretched season decide to cancel their subscription halfway through the campaign?

How does it work elsewhere?

Danish club FC Copenhagen introduced a subscription model in 2018. Since then dropout rates have been at 3% - compared to 10% for season ticket dropouts. Ticketing manager Mikkel Bjerre explains why he proposed the idea.

For a long time we had an issue trying to get season ticket holders to renew each summer. We looked to Spotify and Netflix and decided to apply that to season tickets, and converted to a subscription model.

We charge 79 Danish krone (£9.44) per month which is the same as a basic Netflix subscription here, and it just continues until they want to stop - after the minimum of six months. This is the price of our cheapest season ticket divided over the year and gets you a ticket for every domestic home match as well as guaranteeing your seat for European games.

We are at about 12,000 season tickets now, with 35% of those being subscriptions - which is remarkable growth from four years ago when we were at about 6,500 tickets. It is a very simple idea, and I can only wonder why other teams have not taken on this model - although seven other teams now use it in Denmark.

Teams do depend on cashflow at the start of the season from season ticket sales, and it can be tough for small clubs, but this is only a problem for that first year - after that the cashflow is much better. Smaller teams are seeing a significant increase in sales. At Copenhagen, we didn't depend on season-ticket sales as much and it was about trying to bring in more fans on a regular basis.

I think this model should be able to work in Scotland - it might not make sense for Celtic for example if they sell out season tickets, but it should work for most clubs.

Season tickets per Championship club this season

Season tickets per League One club this season

Season tickets per League Two club this season