Record numbers turn to Football Manager: The game that gave us Tonton Zola Moukoko and Cherno Samba

- Published

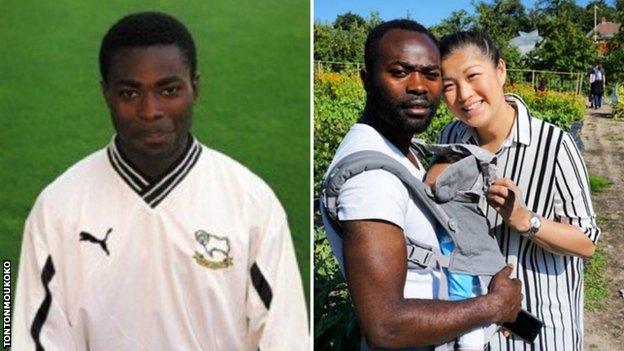

Tonton Zola Moukoko was touted as a future star after signing for Derby as a 15-year-old

With the majority of top-level sport either postponed or cancelled because of the coronavirus outbreak, fans - and even professional clubs - have turned to a familiar source for entertainment: Football Manager.

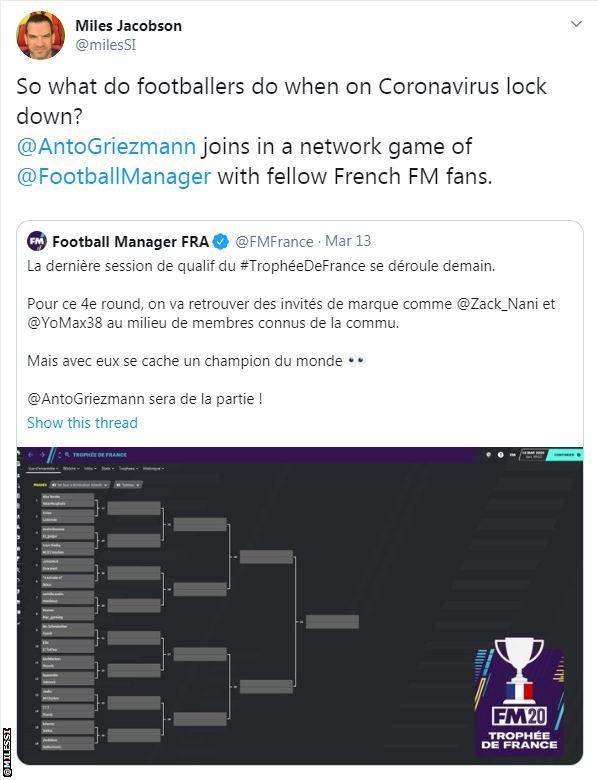

At one moment on Sunday, the football management simulation was being played online by almost 90,000 users around the world, its record number of streams according to director Miles Jacobson.

"Thank you for choosing our work to keep you entertained in this time of self-isolation in many countries around the world," said Jacobson on Twitter.

Meanwhile, Premier League side Watford simulated their scheduled fixture against Leicester City and League Two outfit Leyton Orient asked fans to vote on team selection and tactics during their virtual-reality clash with Bradford City. They lost 1-0.

Here's why so many people have reached for their laptops/tablets/smart phones for a footballing fix while the real game is on hold.

Even France and Barcelona forward Antoine Griezmann has taken to playing Football Manager

Tonton's tale: From Congo to computer screens

"We went to a small, small village in Malaysia. The plane landed, I gave my passport to the officer. He was shocked. 'Are you really Tonton Zola Moukoko?' he asked. 'You can't be the one that was playing at Derby?'"

At the turn of the century, with social media in its infancy, the name Tonton Zola Moukoko adorned Championship Manager fans' forums and was bandied around in-the-know mates like a trophy.

He was a cult hero, a skilful number 10 who - in his own words - "would today compare to Lionel Messi".

Yet he had completely vanished from the radar before his 19th birthday.

Championship Manager, as it began life almost three decades ago, became Football Manager - with a database profiling more than 700,000 individuals on 250-plus pieces of information.

Those touted as future stars usually fulfil their potential in real life, as well on the computer screen. However, while Moukoko - a teenager in Derby County's academy - would usually sign for the likes of Barcelona or Real Madrid in the virtual world, he did not end up gracing the Nou Camp or Bernabeu in real life.

What went wrong in a management simulation so realistic and reliable that it has become a top research resource used by Premier League clubs including Everton and Manchester City?

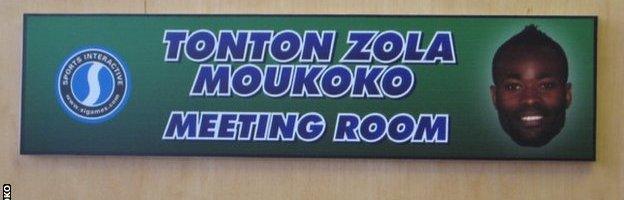

The Tonton Zola Moukoko Meeting Room at Sports Interactive's offices

Born in Kinshasa, Congo, Moukoko lost both his parents at the age of 10 and moved to Sweden to live with his older brother Fedo. It was in Scandinavia his talent began to emerge.

Moukoko's progress at Stockholm-based Djurgardens caught the interest of Italian sides AC Milan, Empoli and Bologna, but the 15-year-old opted for Derby, where his performances for the youth and reserve teams earned him a place in the game's database and the attributes of a future star.

With that came the attention of devoted players of a game Moukoko did not even know existed.

"It was very, very strange," Moukoko tells BBC Sport. "We played at Rushden and Diamonds. There were a lot of people coming around me asking for an autograph.

"I didn't really know what was going on, there were so many people. Then one of my friends, Ian Evatt, said: 'You don't know that you are one of the biggest players in this computer game?'.

"It was just unbelievable. Still now, I have people calling from Australia, France, all over the place. Sometimes they wish me all the best and want me to send them a shirt."

The teenager's stint in the spotlight, in real life at least, was short-lived. The death of Moukoko's older brother meant football slipped to the back of his priorities before he had even kicked a ball for Derby's first team and in August 2002 his contract was terminated by mutual consent.

After two years out of the game, Moukoko was unable to secure a deal back in Sweden's top flight, playing in the lower leagues either side of a stint in Finland.

"In real life I was a good player," added Moukoko. "In the computer game, things turned out the way they should have been. It's spooky really."

And Moukoko would argue his in-game profile was an accurate reflection of his real-life skills.

"He was kind of similar because I was playing midfield or number 10 - passing, dribbling, setting up things," he adds. "If you would compare me to a player today, maybe Messi.

"I enjoyed it, I don't have any problem with that. I was one of the biggest talents in the world at the time at Derby. Things happened around me which changed me a lot, changed my football career.

"I didn't really enjoy football any more. I found it very difficult to sleep for a long time after my brother died. Football was not the right thing for me after that.

"I am happy the way things are now, with my family, but at the time I wish things didn't turn out the way they did at Derby."

'Cherno Samba was a data error'

The depth of the game's database is a result of a scouting network built up over the past 28 years which feeds information back to the game's makers, Sports Interactive.

The team now researches about 2,200 clubs from 116 divisions in 51 countries. They have a scout in every club from the Premier League to National League North and South, while a further 2,000 clubs from lower levels are covered to a lesser degree.

Director Miles Jacobson says the product has become "an encyclopaedia of football" and seeing the young players who impress in the game become good in real life is what makes it feel so believable.

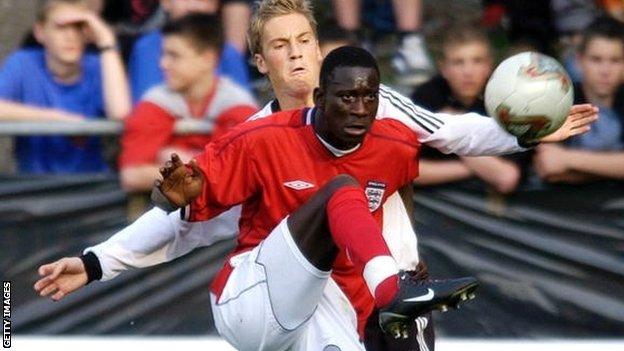

Striker Cherno Samba was another, like Moukoko, who turned into a global superstar in the game's earlier days - but in reality had a career that started in Millwall's youth set-up and then took in Plymouth, Wrexham and Scandinavia's lower leagues.

"I know players like Cherno Samba became legends because of how good they were on the game but didn't end up making it. For me, those players were data errors," Jacobson explains to BBC Sport.

"We have a lot more checks and balances now than we used to, into quite minute detail. So, even though they are really popular among the fanbase, for me they are things we need to make sure don't happen again."

Jacobson does, however, say the story Moukoko's story is "incredibly sad" and he is highly thought of at the Sports Interactive offices, where there is a "Tonton Zola Moukoko Meeting Room".

"The mental side of the game is maybe something we weren't modelling that well then and still aren't modelling as well as ability now - but it's certainly come a long way in-game," adds Jacobson, who admits the ex-Derby forward was always one of his favourite bargain signings.

Cherno Samba began his career at Millwall and played for England's youth teams

Becoming a 'football company'

Football Manager's database is now so comprehensive its use transcends gaming, something that first came to light when Sports Interactive signed a deal with Prozone to allow professional clubs to access it.

No longer exclusive to Prozone, Jacobson says the company is in regular contact with "dozens" of clubs who facilitate the data in different ways.

"We said years ago that we need to stop thinking of ourselves as a games company and think of ourselves as a football company," he explains.

The game's scouts come into their own when providing data on players at under-18 or under-23 level and "working out how good those players are going to become in the future".

"Some clubs will utilise the full, complete database," adds the Watford fan. "Many of them are using it to actually build their own in-house database, but we are the starting point for that.

"Others give us a call about a particular player an agent has recommended to see if it's worth going to Chile to watch him or not."

One of the most sought after pieces of information is a player's previous injuries, key for clubs carrying out medicals on new signings.

"Injury histories are something that are very difficult for clubs to get hold of," says Jacobson.

"They will either refer to the database directly or call us and say: 'This guy had an injury and he was out for this period, do you know what the injury was?' Or even: 'We can't find any information about this player, has he ever been out injured?'"

How do clubs use the database?

The game uses scouts across the world with far more access to players than professional clubs, even at the highest level

The detailed analysis of each individual is so comprehensive clubs trust the database and the rankings awarded to each player

Club analysts can use the database to highlight sought after attributes - age, height, teenagers playing regular first-team football, for example - without leaving their office

Then they can use tools such as Wyscout or Inscouts to view players, or even compare them to members of the club's own squad, before making a decision on whether to send a scout to watch them

It is some journey for a game first released in 1992 and born from Everton-supporting brothers Paul and Ov Collyer looking to entertain themselves at school.

"It was just a hobby for two slightly bored brothers living in the Shropshire countryside who liked football and were discovering home computers were more appealing than feeding the goat," Ov Collyer tells BBC Sport.

"The fact people have used what started as a game - and ultimately that is still what it is - as a serious resource is fantastic, and says a lot about the quality and dedication of the research team that we've assembled over the years.

"But never underestimate how knowledgeable many football fans who devoutly follow their team are.

"By tapping into that expertise, having multiple contributors per team, it shouldn't really be a huge surprise that the end result is a valuable resource."

'Players send videos of them racing each other'

"On your marks, get set..."

It is not just professional clubs who take the database seriously. Jacobson recalls professional players sending mobile phone footage of them racing one another in a bid to boost their speed attributes.

"We have over 1,500 footballers who help us test the game and provide feedback, ranging from global superstars to non-league players," says Jacobson.

"A lot of the players will say: 'I need this stat to be raised or that stat to be raised.' You turn round and go: 'Prove it.' Sometimes it's completely justified."

He explains how one player recently made his debut for a "small nation" and emailed the game to make sure they had it recorded, as clubs were turning away his agent's requests when trying to secure a move.

"It's strange quite how deep it's gone. The leagues I'm talking about there are quite small - but the game has become a great resource for those teams even away from the main database," adds Jacobson.

"No-one should sign a player directly off the back of them being good on the game, but no-one should go and send a scout somewhere far flung off a YouTube video.

"If you get YouTube video of a player looking great and you get another tool based on people on the ground watching that player week in, week out, that's quite powerful."

A place for managers to hone their skills?

Huddersfield Town manager Danny Cowley and brother Nicky both played the game

Former England boss Sam Allardyce recently said games like Fifa and Football Manager were teaching his grandson "how to manage".

"When will the first manager manage at a professional level having learned his trade on Fifa and Football Manager?" he asked.

Jacobson says they already have.

Former Tottenham boss Andre Villas-Boas admitted to using the game as a reference tool when he was Jose Mourinho's chief scout at Chelsea.

Then there is the remarkable case of Vugar Huseynzade, who at 22 was named general manager of Azerbaijani outfit FC Baku, external on the back of his gaming success.

"If you look at most of the successful managers that weren't players, most have grown up playing the game," says Jacobson.

"Andre Villas-Boas was probably the first person to talk about it openly. So Sam is absolutely right to say it is going to happen more often."

A version of this article was first published in November 2017.

- Published29 October 2017

- Published20 November 2017

- Published13 November 2017