When eight teams went down in Scotland's most brutal reconstruction

- Published

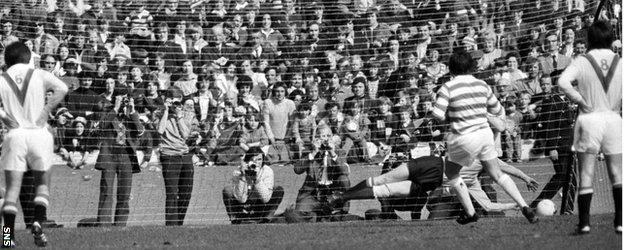

Kilmarnock's Gordon Smith, right, was part of a side relegated on the final day

1975. The Vietnam War ended. General Franco died. Jaws was released. Margaret Thatcher took charge of the Conservatives. The UK voted to remain a member of the EU. And eight teams were relegated from Scotland's top flight.

In a stroke, the "First Division" was stripped of its status as the country's pre-eminent league, replaced by a "Premier Division" of 10 teams - a brutal culling that made the current league reconstruction talks look like a cordial conversation.

Ally McLeod's Ayr United were the only part-time team to earn a place in the hallowed 10 alongside the Glasgow, Edinburgh and Dundee teams, and Aberdeen. St Johnstone also sneaked in on the final day after concluding a rousing run by beating Celtic at Muirton. Motherwell likewise after beating Dumbarton.

"The closer it got, the more the realisation dawned that you didn't want to miss out," says Willie Pettigrew, who was making his breakthrough season for the Fir Park side. "That made it pretty tense but the top 10 was pretty settled - there were always just two or three teams who were in and out."

Andy Gray's 20th goal of the season for Dundee United on the final day not only denied Pettigrew the top scorer crown outright, but it also helped ensure Kilmarnock would be one of those consigned to the second tier.

"Draws killed us - we had 15 of them," recalls Gordon Smith, who would leave for Rangers a couple of years later. "We'd only been promoted the season before but I think we were safe right up until the last game."

Scottish Cup finalists Airdrie went down, too, despite finishing with a win at champions Rangers as well as beating a Celtic side down the stretch that was going for 10-in-a-row.

Partick Thistle also fell after ending with four consecutive draws. Dumbarton, Dunfermline Athletic and Morton had already gone by the season finale. And so had Arbroath and Clyde, neither of whom have ever made it back to the top tier.

Airdrie were one of those relegated, despite beating Rangers and Celtic down the stretch and reaching the Scottish Cup final

The world was changing, so football had to

The following season, those sides would find themselves in a radically recast first division with the top six from the old second tier - Falkirk, Queen of the South, Montrose, Hamilton Academical, East Fife and St Mirren. The remaining 14 sides were left to scrap it out in the bottom division.

That 10-14-14 combination finally unlocked an impasse that had been calcifying for more than a decade. In the post-war years, attendances were growing exponentially. Teams were going deep in Europe. And the domestic squabbles were fiercely competitive, with the 12 seasons from 1954-55 boasting six different Scottish top-flight champions.

Then Celtic won the next title, and the next, and the one after...

That dilution of competition was an ill wind as societal factors in an rapidly-changing Britain soon coalesced into a storm. "From the mid-'60s, there was a drop off in attendances," says David Thomson, who left his role as Scottish Football League operations director in 2013 after 33 years with the organisation.

"It wasn't about the quality on show, because there were some tremendous players and teams. But people were becoming more affluent and could do other things with their time; more sport was on television; working weeks were changing; then there was Celtic's dominance; hooliganism; the three-day week; a recession. All these things played a part and it was a situation beyond football's control, in the most part."

Reconstruction was first mooted in the mid-'60s after it emerged crowds had dipped by about half a million. Thomson recalls three leagues of 14-12-12 being suggested. Then 12-14-14 and 16-12-12. Rangers even went to court to try and rid the SFL of its bottom five clubs and form two 16-team divisions, only to lose their case.

Then in 1967 - an otherwise glorious year for the Scottish game - Third Lanark died. A club who had finished third in the top tier as recently as six years earlier were struggling financially as well as on the pitch and, suddenly, there was wider acknowledgement that things needed to change.

"The 18-team leagues created meaningless matches so there was a soft underbelly," says Thomson. "Invariably there were clubs in the top tier - where it was two up, two down - who had absolutely nothing to play for so people would just stop going.

"At best, with the population at that time, there were maybe 10 clubs capable of supporting full-time football and I think only seven had that status when I started in 1980. So a number of clubs were just out of their depth."

'It made every game more nerve-wracking'

Rangers won the title to deny Celtic 10 in a row

During the 1973-74 campaign, agreement was finally struck. Ferranti Thistle would be welcomed as members - becoming known as Meadowbank Thistle - to address the imbalance left by Third Lanark's demise. And the 18 top-flight and 20 second-tier clubs would play the following season knowing what would await at the end of that term.

"We knew the change was coming but it was a massive thing to go from 18 to 10 - nearly half the league are playing to stay up," says Smith. "It makes every game more nerve-wracking. There were seven or maybe more matches that were relegation battles every week and probably 12 clubs playing to avoid relegation."

For Pettigrew, who only broke through midway through the season, the focus was simply on staying in the Motherwell team. "I know there was a lot of talk about it and tension," he says. "In the first half of the season, we were just trying to stay in touch but we eventually realised we could make the top 10 and got to the point when it was that one-off game on the final day and we won pretty well in the end."

Did smaller divisions work?

Motherwell would go on to finish fourth in the first season of the Premier Division, while Kilmarnock would earn promotion after finishing runners-up to Thistle in the second tier.

But the new format was not an immediate success. St Johnstone were cut off early, eventually finishing 21 points adrift of Dundee, who were also relegated despite gathering the same number of points as Aberdeen and Dundee United. Just 13 years earlier, the Dens Park side had played in a European Cup semi-final.

Hearts, Hibernian and Motherwell would all go down in the subsequent seasons; further victims of a structure in which 20% of the sides were relegated at the end of a 36-game campaign.

It took until 1986-87 for the top league to be expanded to 12 teams, but that lasted only two campaigns. Then it swelled again to 12 in 1991-92 for a further three seasons until the advent of the fourth tier meant a return to a top 10 in 1994-95.

That was it until the 12-team Scottish Premier League debuted in 2000-01, with the division splitting after 33 games. It has remained that way since, amid sporadic cries for a return to a bigger top league and a return to how things used to be in 1975.

"These smaller divisions were going to revolutionise football," says Pettigrew ruefully. "But we've fumbled our way through it. We'd be better retracing our steps and bringing the top four in Championship into a 16-team Premiership."