Bayern Munich: Branko Zebec, the brilliant, damaged manager who helped shape a giant

- Published

- comments

Zebec was a brilliant chess player who had excelled in the study of maths and physics

Branko Zebec deserves to be remembered as one of the greatest coaches of his era, and yet his name is largely unknown.

His tactical genius was extraordinary, his unique story tragic in the extreme. Zebec led Bayern Munich to their maiden Bundesliga title in 1969 and repeated the feat against all odds with Hamburg 10 years later.

He significantly influenced the careers of numerous superstars, and Paul Breitner - one of only four players in history to have scored in two World Cup finals - describes him as the best coach he worked with.

Zebec was a tough and complex person who referred to himself as a dictator, yet struggled to cope with his own issues. He was ridiculed for falling asleep on the bench during matches and would appear drunk at news conferences, often making bizarre statements.

His contribution to establishing Bayern as a major force in European football cannot be overstated, but his career - and indeed his life - ended prematurely because of desperate alcohol addiction.

Those who remember Zebec cherish his positive sides, looking back. Take the legendary Bayern goalkeeper Sepp Maier.

"When Bayern won the league and cup double in 1969, that was the beginning of what the club is today," he tells BBC Sport.

"Zebec's part in that was massive. He laid the foundations, and played an important part in turning Bayern into a top club. He was the best tactician."

That particular double triumph of 1968-69 was unexpected.

Bayern were not considered a top club back then. They had not seriously competed for the German league title since their first national title of 1932 in the pre-Bundesliga era. After president Wilhelm Neudecker appointed a promising young Croat as manager in the summer of 1968, everything would quickly change.

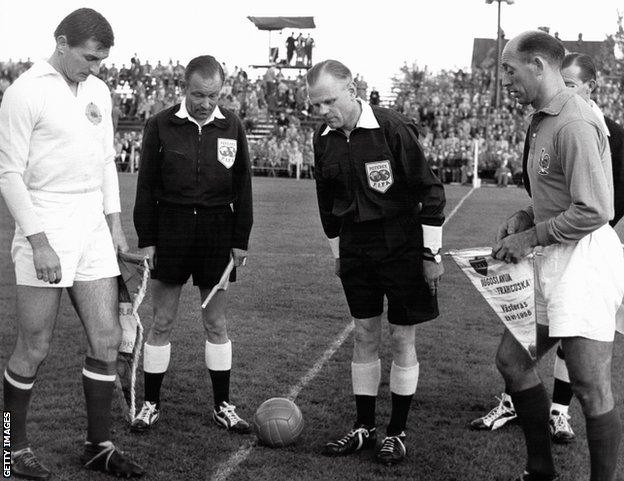

Then 39, Zebec had been recommended by his predecessor, Zlatko Cajkovski. The pair had been key players for Yugoslavia in the 1950s, and Cajkovski respected his leadership. Zebec captained Yugoslavia at the 1958 World Cup.

Zebec (left) pictured at the 1958 World Cup in Sweden, where Yugoslavia were knocked out by West Germany in the quarter-finals

Neudecker believed that a strong personality was needed to turn Bayern into a winning team, but even he was stunned by Zebec's decisiveness.

The changes were swift. Zebec implemented a patient passing style that is described by veteran Kicker journalist Raimund Hinko as "tiki-taka before its time". He found the best position for Hans-Georg Schwarzenbeck by turning a left-back into one of the best centre-backs in the world, with Franz Beckenbauer maturing alongside him.

Defence was more important than attack for Zebec, and his Bayern were a cautious presence in a division used to very open games. However, he also helped get the best out of Gerd Muller's prowess in the penalty area and the striker flourished into a scoring machine, netting 30 goals in 30 Bundesliga matches over 1968-69.

The blend resulted in a very convincing title win, as Bayern finished eight points ahead of Aachen. "It was a real surprise, incredibly achieved by using only 13 players in the entire season," Hinko says.

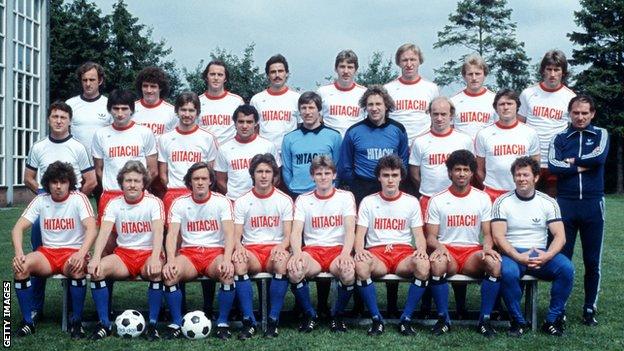

Bayern's double-winning team of 1968-69. They won the club's second national league title, following that of 1932 in the pre-Bundesliga era

Fitness was crucial. Zebec's physical training sessions were notoriously tough.

"He forced his players to take part in very long running activities, even in deep snow. It was so exhausting that they would faint," Hinko adds.

"Branko was a difficult and stubborn person - an absolute authority figure. But he could also be sensitive and kind in conversations. He was an introverted man with a faint smile and a fine sense of humour. He liked alcohol too. Wine, beer, cognac, vodka, rum."

Many coaches were fond of drinking in those days and the severity of Zebec's problem wasn't immediately obvious. It was easier to make fun of it. Zebec was nicknamed Fernet-Branko behind his back - after the Italian bitters brand Fernet-Branca.

However, Zebec suffered from diabetes and after having a difficult pancreatic operation in 1970 was not supposed to consume alcohol at all. His addiction was destructive, a grave illness that wasn't taken seriously enough.

"We respected him whether he was drunk or not," recalls Breitner, who played under Zebec later in the coach's career, at Eintracht Braunschweig in 1977.

"I was lucky to work with a lot of great specialists, including Miljan Miljanic and Udo Lattek, but Zebec was the best coach," he says.

"Others, like Beckenbauer and Muller, would say so too. Branko was tough, but correct and fair. He treated everyone equally and didn't distinguish between big stars and young players. He might have been a dictator, but he was a good dictator.

"He was unpredictable. At times, two training sessions would be scheduled, but then he would announce that they were cancelled and we just sat and drank coffee. Branko was different. There was no-one like him and I love people who are different.

"His problems were known to everyone, and they started back at Bayern, but it wasn't our job to try and help him."

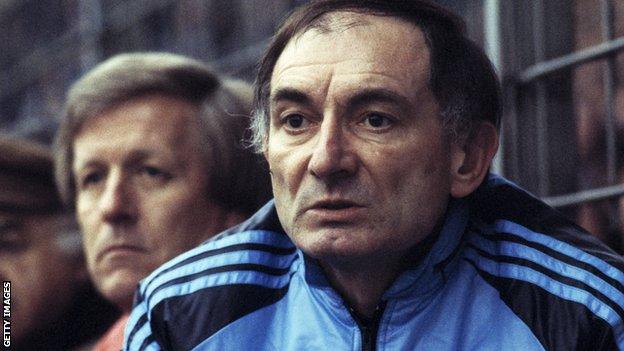

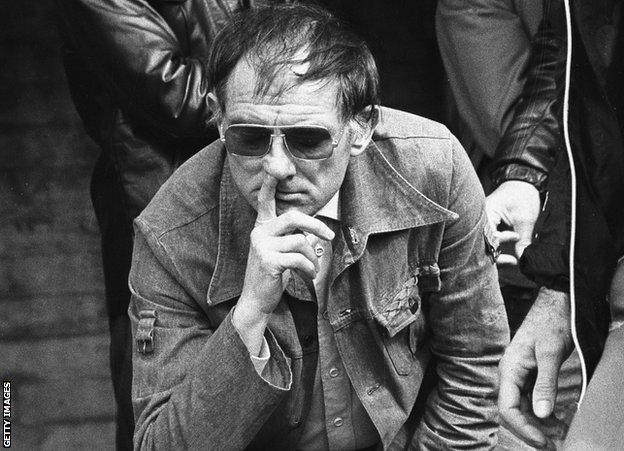

Zebec's health deteriorated significantly over the course of his career owing to alcohol abuse

Those problems were not behind Zebec's sacking at Bayern in March 1970, however. His style was just way too authoritarian for the club's liking. He insisted on making all the decisions himself - and that made life difficult for president Neudecker and team manager Robert Schwan.

Such behaviour was tolerated so long as Bayern were on top, but the leadership took their first opportunity to get rid of Zebec when results deteriorated slightly during the next season. Borussia Monchengladbach won their maiden title at Bayern's expense that term, led by the genius of Gunter Netzer - a man who greatly appreciated Zebec even though he never played under him.

Eight years later, Netzer became a successful sporting director at Hamburg and his most important decision was to appoint Zebec as manager in the summer of 1978, when the club was in deep crisis. Hamburg had finished 10th, looked disorganised, and Kevin Keegan - only purchased a year earlier from Liverpool - was close to leaving.

Zebec had spent the intervening years without great distinction at Stuttgart and Hajduk Split, before joining Braunschweig in 1974.

But just like at Bayern, his impact at Hamburg was immediate. The north German side incredibly won their first Bundesliga title in his debut season in charge. Keegan scored 17 goals and won the Ballon d'Or in 1978 and 1979.

Felix Magath, the dominant midfielder at the heart of that success, recalls: "Nobody knew where we were going and some even feared we could be relegated. Not even the most optimistic of fans dared dream about winning the title.

"Zebec was the main reason behind our success. Winning was his only priority and he taught us how we needed to play in order to do so. He was very intelligent. He turned an average team into one of the best in Europe."

Hamburg's team photo in 1978. Zebec is on the far right of the second row. Keegan is second from the left, top row.

Zebec's training sessions continued to be extremely tough.

"Our training ground in Ochsenzoll was the size of four football pitches," says Jimmy Hartwig, Magath's young partner in the Hamburg midfield.

"Zebec forced us to run 60 laps around it in 35C. It was extremely difficult, but we knew that fitness helped improve our game. He was one of the most honest men I have ever met. Even though he was strict, he was a father figure to me and he knew how to listen. Branko was the hero of our title triumph."

In his second season at Hamburg, Zebec nearly led the club to the 1980 European Cup. The German champions outplayed Nottingham Forest in the final in Madrid, but Brian Clough's team scored early and managed to keep a clean sheet despite Hamburg's best efforts.

Italian newspaper La Gazzetta dello Sport amusingly summed up the event by claiming that "Forest showed how English teams can implement Catenaccio, external".

Magath says: "There is no doubt that Zebec and Clough were the most influential coaches of their time. It is possible to compare them as two strong personalities who had their own ideas and followed their principles, no matter what. They would even defend their opinions against the chairmen of their clubs."

While Clough lifted the European Cup, Zebec's greatest continental success would remain the stupendous 5-1 thrashing of Vujadin Boskov's Real Madrid in the return leg of the semi-finals that year. An even more significant incident took place just four days previously, when Hamburg faced Borussia Dortmund in the Bundesliga.

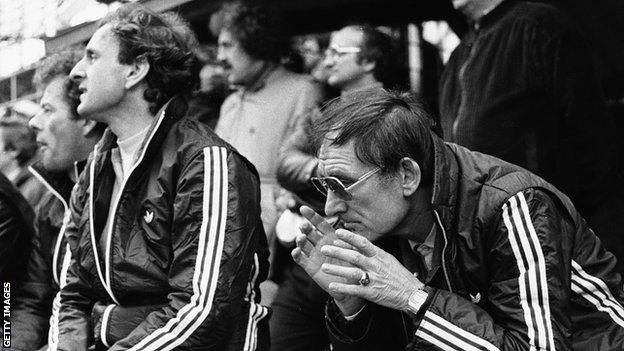

Zebec, pictured in Hamburg's dugout during a Bundesliga match against Dortmund

Zebec was nowhere to be seen when the team bus departed for Westfalenstadion, because he was drunk and overslept. Upon waking up, he decided to drive to Dortmund himself, only to be stopped by police who discovered a 3.25 level of alcohol in his blood - people usually pass out when they are that intoxicated.

The car was confiscated, but Zebec took a taxi, arrived at the stadium on time, and was allowed to sit on the bench. That was a grave mistake, because images of him falling asleep made big headlines.

Until that point, the club had somehow concealed Zebec's addiction from the public eye, but now that became impossible. The phenomenal win over Madrid just a few days later was even more stunning in those circumstances, but the Croat's bright star was falling just as fast as it had risen.

Hamburg ended the season empty handed, finishing second behind Bayern by two points in the Bundesliga, and the situation deteriorated. In July, when Zebec turned up to training totally drunk, the club officially stated that "another incident of a similar nature would make further co-operation impossible".

Such an incident occurred in December 1980, when Zebec appeared drunk at the news conference following a win over 1860 Munich. He pushed Netzer aside on his way to taking his chair and that was that. Hamburg terminated his contract, and the sporting director was left distraught.

"I knew about Zebec's addiction before signing him, but didn't understand what that meant," Netzer would later say. "The story with Branko affected me more than anything else in football. He was a magnificent guy, and that's why it hurt so much that I couldn't help him."

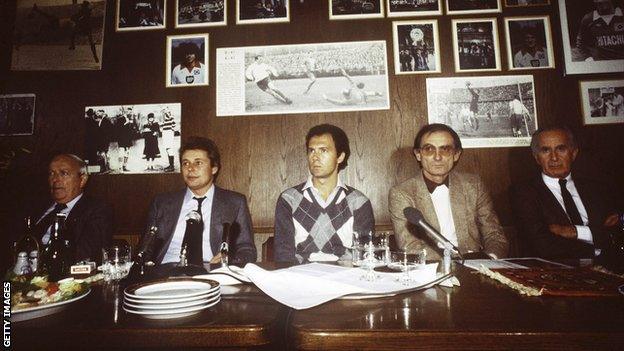

Zebec (second from right) and Beckenbauer (centre) were briefly reunited at Hamburg in 1980, before the manager's departure

Those close to Zebec witnessed in despair as his life and career fell apart. His talents were broad - he was a brilliant chess player who excelled in the study of maths and physics. He was capable of winning over footballers, but couldn't beat alcoholism.

Zebec didn't go down without a fight, of course. In the summer of 1981, he joined Borussia Dortmund, turning them into a remarkably organised outfit and leading a rather average squad to sixth place and Uefa Cup qualification. Fans fell in love with him but the club decided against extending his one-year contract. The continuing off-field problems were way too serious to ignore.

Zebec departed his last German club, Eintracht Frankfurt, in October 1983. During a defeat at Hertha Berlin, he couldn't stay in his seat and slept through most of the game. Frankfurt acted fast.

In order to prevent a scandal at the post-match news conference, the kitman wrapped Zebec in a carpet and smuggled him out of the stadium past the journalists. Nobody noticed when the carpet was loaded on to the bus. It was a grotesque and disastrous exit from football for a man whose genius could have taken him to the very top.

His influence lived on, at least as far as Magath is concerned. The midfielder became a tough and demanding coach himself, winning two Bundesliga titles with Bayern and leading unfashionable Wolfsburg to their sensational league triumph in 2009.

"Zebec was the most important person in my career and his ideas definitely formed the foundation for my work as a coach," says the former Fulham manager. "Like Branko, I aspired to develop teams through hard work and dedication and always improve players personally."

Sadly, Zebec was not a witness to Magath's new career. He died in 1988 at the age of 59, beaten by the only enemy he had ever feared.

If you, or someone you know, has been affected by alcohol addiction, information and support is available at BBC Action Line.