Jack Grealish: He has made mistakes but is England midfielder misunderstood?

- Published

Jack Grealish's goal against West Ham on the final day of last season helped Aston Villa retain their Premier League status

"You see a lot of stuff written about him now and it upsets me," sighs Alan Sheehan. It's been more than six years since he played alongside Jack Grealish, who spent 2013-14 on loan with Notts County in League One, an 18-year-old experiencing his first taste of senior football. That was the only season they were team-mates, but Sheehan connected with Grealish in a way similar, it seems, to most who have crossed paths with the Aston Villa captain.

At 24, Grealish's stock has never been higher. After rescuing Villa from relegation with a late goal against West Ham on the final day of last season, he's being tipped for greater things. A move to one of the Premier League's biggest clubs might soon be on the cards; likewise, following his first England call-up, international caps.

But the mistakes of Grealish's recent past colour perception of him. In 2015, during his breakthrough season with Villa, he made an unwanted appearance on newspaper front pages for inhaling from balloons containing nitrous oxide, also known as "laughing gas", at a party. Two months later, he was pictured apparently intoxicated and passed out while on holiday in Tenerife. And earlier this year, he was charged with two driving offences after crashing his car while appearing to contravene coronavirus lockdown restrictions in March.

His maturity, his readiness for all that awaits him, has been questioned.

"He almost had this nonchalance about him," says Michael Watts, Villa's former head of performance. "Sometimes maybe people take it as arrogance but I never saw that in Jack. He was such a kind, gentle kid."

It's not that those who know Grealish best want to make excuses for his indiscretions. It's not that they don't recognise the public caricature painted of him, with his socks slung low, coiffured hair and carefree swagger. But they understand that this accounts for only a small proportion of who he is. They wish the other aspects of Grealish's character were given equal billing.

One of the pictures which appeared to show Grealish lying on the street in Tenerife in 2015

Shay Given fires the ball high into the air above Villa's Bodymoor Heath training ground. As it begins to fall back to earth, there is a quick realisation that the ball will return in the form of a test. The 15-year-old standing beneath it has long been accustomed to feeling the eyes of others fixed on him, a standout local talent within the club's academy since he joined aged six. It doesn't seem to affect him that the stares he attracts in this moment belong to the manager and coaches he needs to impress, the players whose approval he must earn. Grealish kills the ball dead.

Senior players Richard Dunne and James Collins nodded their approval. Another, Stiliyan Petrov, was clearly impressed.

The other boys in Villa's academy knew Grealish was destined to star for the club he'd always supported. His ability was evident, from his key role in a 2012-13 triumph in the NextGen Series - a precursor to the Uefa Youth League - to the way, before training sessions on the indoor pitch, he'd volley the ball through a basketball hoop from 50 feet away.

His team-mates appreciated that his status as the club's premier prospect was not a result of talent alone, though. "I've never seen him have a bad day where he sacks off training," says Lewis Kinsella, who played with Grealish in Villa's youth teams. "He's so competitive and he wants to win. That's probably why he's at where he's at."

"You never really got any problems with Jack," added Watts. "He knew that there was work to be done."

Simon Heslop was only 26, but he'd already clocked up the mileage of a wily veteran. Including loans, Stevenage was his 10th club. His career had taken in spells at every level from the second tier down to the fifth. He knew how to deal with over-confident, dribble-happy teenagers who viewed his current level, League One, as a stepping stone.

So when Grealish sauntered infield from the left, jinking past one Stevenage player, then another, Heslop took action. He clattered into the 18-year-old, a violent, full-speed smack of his right leg and hip against the winger's left side. The ball, never of Heslop's concern, rolled away from the scene.

Grealish was just 16 when he was named among the substitutes for a Premier League game against Chelsea in March 2012. But that was merely a device to bump up the youngster's value and ward off growing interest from other clubs. His first exposure to senior action would instead come via a loan with Notts County the following season.

When Grealish arrived in Nottingham, his new team-mates saw skills that would upgrade their attack - a breezy dribbling style, an eye for a pass and crisp ball-striking technique. But they were struck most by his physicality, a muscular robustness ready-made for the rigours of third-tier football.

"He was only a young boy but he had this physique," remembers Sheehan, County's captain at the time. "He was built like a top athlete. 'Who's this kid here?' was the first thing I was thinking, because he looked serious."

It has been well documented that Grealish was the most-fouled player in the Premier League last season. He drew similar attention with County, only in a more physically intimidating league, without the watchful glare of video assistant referees to deter his assailants.

Grealish was fouled more than any other player during the 2019-20 Premier League season, despite Villa having less possession than many other teams

"Coming up against an 18-year-old as a senior pro, you get frustrated that you can't take the ball off this kid," said former Magpies forward Enoch Showunmi, "so you use other means to try to see if he has that mentality to keep getting fouled, to get hit and still want the ball. And you could see back then that he had it."

The root of Grealish's physical resilience can be traced back not to the training pitches of Bodymoor Heath but rather to the Pairc na hEireann, Solihull's hub of Gaelic sports.

Grealish was introduced to Gaelic football as an eight-year-old, taken along to a training session at John Mitchels Club by an uncle. Grealish's grandparents on his maternal and paternal side hail from Ireland - whom he represented at youth level before declaring for England in 2015 - and the family retain a deep connection with the country. Many of his cousins still play Gaelic football in the Birmingham area.

And it was through Gaelic football that Grealish first got accustomed to performing before the masses. He played and scored for Warwickshire under-12s in front of 70,000 at Dublin's Croke Park at half-time of the Leinster final, one of Ireland's biggest sporting events.

His playmaking and dribbling abilities translated well to the Gaelic game. His John Mitchels side became the first non-Irish team to reach the semi-finals of the Feile tournament in Birmingham, having beaten favourites Castleblayney. In another tournament semi-final, he sparked a comeback from a 13-point deficit with a solo goal, beating six or seven opponents to score.

"For someone so young, he knew his way around the pitch," says Kevin McGinnity, who coached Grealish at John Mitchels. "He's just a natural."

Gaelic football can be a brutal pursuit, its tackling practices sharing more in common with rugby than soccer. The youth version of the game is supposed to be non-contact, but Grealish found that was rarely the case.

"Jack took a lot of knocks. But he was able to take it," says McGinnity. "It wouldn't faze him. He wasn't tall for his age but he was strong."

So when Heslop hurtled into him in the first half of Notts County's 1-0 win over Stevenage at Broadhall Way in January 2014, Grealish was already used to being singled out for such rough treatment. The impact forced him from the field, but it didn't dissuade him. He was back the next game, driving at his full-back, even scoring in a narrow loss to Peterborough.

Grealish returned to Villa in May of that year, having helped County survive in the division. His first season of senior football comprised of 38 appearances, five goals and innumerable hard knocks.

"He went away a little boy and he came back a man," says Bryan Jones, Villa's former academy manager. "It changed his character, changed his outlook on the game.

"He said to me, 'BJ, I don't really want to play down at that level. It's time for the hard work. This is where I want to play.'"

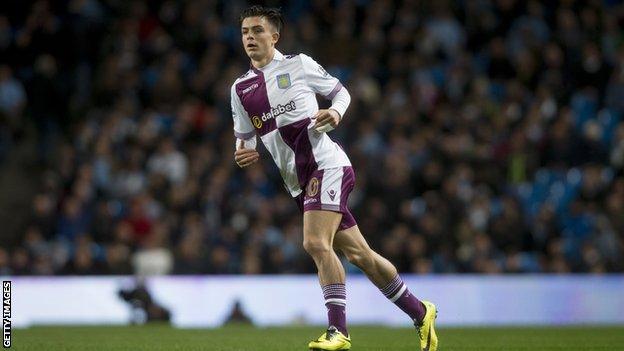

Upon his return, Grealish was handed a Villa debut on the penultimate day of the Premier League season, playing the final minutes of a 4-0 loss to Manchester City.

"He realised that playing first-team football is a man's game: there are going to be kicks, there are going to be bruises," says goalkeeper Brad Guzan, who played alongside Grealish at Villa until 2016. "But I think you saw his eagerness to want to succeed that much more."

It is six years since Grealish first appeared in the Premier League

Viewed from behind the goal, one man stands out among the cluster of black-and-white-shirted Notts County players awaiting a corner kick. His jersey is untucked; his socks are rolled down to his ankles. He stands on the edge of the penalty area as the ball is twice swung into the Gillingham box.

When it is headed clear, he collects the ball on his chest, 25 yards from goal. He runs. Three times he feints to shoot; three defenders are beaten. When he finally lets go, his shot rises high into the roof off the net.

But he keeps running - behind the goal and over to Meadow Lane's Derek Pavis stand. Kevin Grealish races down from his seat to meet his son. They hug, celebrating Jack's first goal as a professional footballer - and everything they've overcome to get here.

The Villa captain was just four years old when his younger brother Keelan died of sudden infant death syndrome. The tragically lost sibling is never far from the Grealish family's thoughts. When he was eight, Grealish donated a trophy he'd won to his school to honour his little brother's memory. The Keelan Daniel Grealish Memorial Cup is still the esteemed prize of sporting events at Our Lady of Compassion Catholic Primary School in Solihull. Ten years later, he dedicated his solo goal against Gillingham to Keelan.

If any positivity is to be gleaned from such heart-crushing loss, it is in how it reminds us to cherish loved ones, to appreciate every minute. When his mother, Karen, would come to collect him from academy training sessions, Grealish would run over to his youngest sister, Hollie, who has cerebral palsy, and hug her. After his man-of-the-match performance against Liverpool at Wembley in the 2015 FA Cup semi-final, he again ran to Hollie, sweeping her into his arms.

"All athletes have a purpose," adds Watts. "I don't think Jack's was money. I think it's for the love of football and probably his family.

"There are many things that can create resilience, and it's usually adversity. That can be adversity in a personal life, adversity in sport. Somewhere, this adversity creates resilience in you and mental strength. He definitely has that. That drive to want to succeed."

Given his high-profile misdemeanours, the average football observer might be surprised to learn that those who know and have worked closely with Grealish, almost unanimously, describe him as mature. But maturity can take several forms.

He showed great maturity, for example, in his restraint when assaulted by a Birmingham City fan during last year's second-city derby; also in the composure he demonstrated to continue the game and score the winning goal.

"I think he's always been able to lead by example on the pitch," says Kinsella, who saw leadership qualities in a 15-year-old Grealish. "And if he disagreed with something, he'd never keep his mouth shut, he'd always have something to say."

Some of his Notts County team-mates, under the strain of a relegation fight, would bark at Grealish in training to release the ball quicker or track back more urgently. He didn't bite back. He learned, improved, but never compromised on his unique style of play.

Even after the standout performance of his nascent career, pulling Liverpool apart in an FA Cup semi-final as a 19-year-old, his focus quickly returned to self-improvement. Within days of that game, he was talking to his coaches about what he could have done better.

Grealish knows he isn't perfect, on or off the pitch. He's a work in progress, and he's never run from hard work.

Liverpool's 30-Year Wait: Behind the scenes of their title triumph

Introvert or extrovert: Can you truly be one or the other?