Atalanta: The underdog Champions League challengers with a 'special' link to fans

- Published

Atalanta's home ground - Stadio Atleti Azzurri d'Italia - is known as Gewiss Stadium for sponsorship reasons

As the first days of autumn appeared in the Italian city of Bergamo, final adjustments were being made at Atalanta's Gewiss Stadium.

New lights, new stands, a new facade. This modest 21,000-seater was preparing to host Europe's grandest club competition, just a few months on from the remarkable summer that followed tragic spring.

In August, Atalanta were cruelly defeated 2-1 by Paris St-Germain in the Champions League quarter-finals, two goals conceded between the 90th and 93rd minute ending an impressive maiden run during which 'home' was Milan's San Siro.

On Tuesday they host Liverpool, having taken four points from their first two group games - a 2-2 draw at home to Ajax and a 4-0 victory at FC Midtjylland.

Within the club and among its fans, Atalanta's second bite at Europe's best, and the exciting draw they received, is being treated as "a gift" after a period of great trauma.

Back in February, as this underdog team was winning admirers across the continent, the first infections began to surface. Bergamo and the surrounding Lombardy region was an early Covid-19 hotspot. In this part of northern Italy, the death toll quickly rose to a terrifying daily count. Almost 16,000 people had died by May., external

"We called it an earthquake, a tsunami," says Dr Fabio Pezzoli, health director of Papa Giovanni XXIII hospital and an Atalanta fan.

"As a native of Bergamo, when I saw scenes of military trucks carrying coffins it was very hard emotionally. I myself lost a family member."

Around 45,000 fans attended Milan's San Siro to watch Atalanta and Valencia in February. Bergamo's population is about 120,000

Dr Pezzoli was at the San Siro for Atalanta's Champions League last-16 first leg against Valencia. It was on 19 February, and almost 45,000 fans attended.

It was supposed to be the most important game in Atalanta's history, a moment of joy and pride. And truly it was: La Dea (The Goddess) defeated their Spanish opponents 4-1, fans were hugging and kissing in the stands. The celebrations spread, as did the virus.

Dream turned into nightmare. The game was later identified as the source of a huge cluster of Covid-19 cases and one of the biggest reasons why Bergamo became an early epicentre of the pandemic that has since changed the world so much. It was described as a "biological bomb".

"I feel awkward about that. Even if we are not guilty, we couldn't know," remembers Dr Pezzoli. "It clearly was a cluster, a source of contagion. But well… Atalanta in the last 16, how could we miss it?"

Nicolo Manclossi also attended. This 30 year-old fan hasn't missed any of his team's games since childhood, when he began going to the stadium with his father, when the club was still in Serie B, Italy's second division.

"It was a dream for any supporter, tens of thousands went from Bergamo to Milan, it was like an exodus," he says.

"It was only after that we realised. Within a short time, literally everything stopped. Life was extinguished."

Military police officers - carabinieri - were brought in to respond to Bergamo's Covid-19 outbreak

By 8 March, the Italian prime minister Giuseppe Conte had announced a 'lockdown' for Bergamo and its region.

Atalanta were allowed to play their second leg against Valencia in a Mestalla Stadium empty of supporters. The victorious 8-4 aggregate scoreline contrasted with the dramatic situation Bergamo was facing.

In their measured celebrations, players showed their support for their city, exhibiting a T-shirt reading: 'Bergamo it's for you. Don't give up.' It would be the players' last action on the pitch for a long time.

As with all other activities, football finally stopped, leaving Atalanta's epic interrupted. But the moment revealed the strong ties between club and city.

"Being a fan of Atalanta is part of the identity of Bergamo," says Andrea Valesini, editor-in-chief of local newspaper Eco di Bergamo.

"During the lockdown, no player left the city. They stayed here and shared the pain of the people.

"The captain Alejandro 'Papu' Gomez launched an international solidarity campaign for the hospital, the kind of thing that strengthens the link between the people of the city and the squad."

Atalanta's fans also played a key role during the pandemic, using their experience in organisation and creativity. They developed solidarity networks and helped build a field hospital in 10 days, that housed 200 beds.

Although Italian football 'ultras' often suffer a bad reputation, the attitude they showed during the lockdown injected a spirit of resilience and hope to the whole city.

Marco Pirovano, 38, was one of the many fan volunteers. He spent his weeks distributing food to hospitals and to aid workers.

"Football is a pretext for everything," he says. "I'm glad to contribute to the needs of my city. Helping each other is part of our mentality."

At that time, the most popular sport on Earth became a pretext for solidarity.

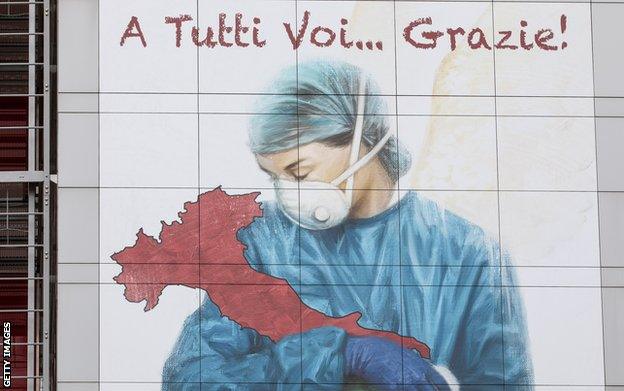

'To All of You... Thank You!' A mural outside Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital pictured in March pays tribute to health workers

"Atalanta is something special. It's not about winning trophies," affirms Fabio Gennari, founder of online media outlet Radio Dea.

"There is a symbiosis between the city and the club that is difficult to explain. They are linked by the land, by blood."

Humble and hardworking, talented and resolute, the Atalanta team forged under visionary coach Gian Piero Gasperini and emblematic captain Gomez was built through effort and determination. A beauty hidden in Milan's shadow, like Bergamo itself.

Inside the collar of Atalanta's jersey, a slogan is written: "The shirt always sweats."

The people of Bergamo strongly identify themselves with their team, even more so since former player and local businessman Antonio Percassi became club president for the second time in 2010.

Back then, Atalanta were playing in Serie B and facing economic difficulties. Ten years on, the club is one of the strongest teams in Italy and owns its stadium.

"We promised to give back to Bergamo the Atalanta they deserve," he told the local newspaper Eco di Bergamo. "It's a family story", he added, pointing to the importance of his sons on the club's board.

Since assuming the presidency, Percassi has managed to strengthen relations between the city and the club. He even started distributing Atalanta jerseys to newborns in local maternity wards.

The most influential figure in Atalanta's success though, is manager Gasperini.

"There is a football before Gasperini and a football after Gasperini. Like before and after Christ," says journalist Gennari.

Gasperini has developed his exciting 3-4-3 formation around a solid squad without stars, putting the collective before the individual. Appointed in 2016 after leaving Genoa, the Italian coach has transformed Atalanta.

Gasperini, 62, has also previously coached Inter Milan, but lasted only three months

They finished fourth in his first season, seventh in 2018 and third in 2019 and 2020, when they scored a club record 98 league goals. They also reached the 2019 Coppa Italia final, losing 2-0 to Lazio.

Gasperini has brought the best from more experienced players whose careers had stalled: attackers Luis Muriel, Duvan Zapata, Josep Ilicic and Gomez have all found in Bergamo the perfect place to play their football.

Then there is the club's outstanding work in the transfer market. Most of the players Atalanta sign are purchased at bargain prices, and most have since seen their values rocket in line with performances.

Wing-back Robin Gosens was bought from Dutch side Heracles Almelo for around £800,000 in 2017. Now the 26-year-old is said to worth about £25m and was this year called up to the German national team.

Belgium defender Timothy Castagne, 24, was signed for close to £6m from Genk in 2017 and sold to Leicester for a reported £21.5m this summer.

Dejan Kulusevski - a standout upcoming star of Serie A - joined Atalanta's youth academy in 2016, moving from IF Brommapojkarna in his native Sweden at 16. After impressing on loan at Parma last season, he was sold to Juventus for around £30m in January.

Earlier in October, Manchester United announced a £19m deal to sign 18-year-old Amad Diallo, a winger from the Ivory Coast who joined Atalanta aged 13 in 2015.

In the past five years, Atalanta have made a net profit of around £80m from transfer dealings, all the while breaking their own record signing fee three times (Muriel, who joined for a reported 18m euros (£16.4m) from Sevilla in 2019 is their most expensive ever purchase).

So far, it has been a hugely successful model - both on and off the pitch.

Atalanta welcome Liverpool in the Champions League on Tuesday

Walking in the streets of Bergamo helps to convey Atalanta's centrality to daily life. Flags, graffiti and the club's banners can be spotted everywhere.

This season they have started Serie A with four wins and two defeats from their opening six games. Their brilliant Champions League debut may have ended cruelly, but supporters are hoping for even better to come.

"We are allowed to dream," says Gennari. "Especially after what happened, I think the response on the pitch was a way to bring joy again after so much pain."

The resumption of football with empty stadiums doesn't satisfy all the supporters. "Football has to be for everyone or for no one," argues Marco.

But for the majority, football is seen as a way to move forward.

"Life continues," says Gennari. "A friend of mine lost his father because of Covid-19. He used to go to the stadium with him. And now, every time Atalanta is playing, he feels his father close to him. It's a way to go on."

While the second wave of Covid-19 is growing in Europe, the future remains unclear. But the stars of the Champions League are shining above Bergamo.

This is the kind of renaissance the city was waiting for - to see their team taking on historic giants of the European game. Ajax at home was special. Liverpool will be too.

"Since Atalanta's birth in 1907, nobody could have imagined that we would one day play with these teams, in these stadiums. It's wonderful," marvels Nicolo.

"As fans, it's obviously a pain that we can't go there. But let's hope the situation improves quickly so we can live again the beautiful atmosphere of these grounds."

Gennari adds: "After the worst storms, the sun always rises again. As long as there is life, there is hope."

Alexandros Kottis and filmmaker Gabriel Babsi are working on a documentary film, telling the story of Atalanta and Bergamo's extraordinary year.