Notts County and the conman: Following your team through a football scam

- Published

Russell King was the fraudster behind the 2009 Notts County takeover

The first game of the new football season feels the same no matter what team you support. There's a heady mix of excitement and anticipation, a first look at new signings, a clean slate to dream that this might be the year.

When I took my seat at a packed Meadow Lane for Notts County's first game of the 2009-10 season, that first-game buzz was like nothing I had ever experienced, because something incredible had just happened.

Less than a month earlier, in July 2009, League Two Notts County had been taken over by a mysterious consortium called Munto Finance. They had stated their bold ambition to reach the Championship within five years and pledged to back those plans with untold wealth.

The club's younger fans, myself included, immediately began to dream of surpassing city rivals Nottingham Forest. The more battle-hardened supporters took some of the loftier claims with a pinch of salt. They had seen too many false dawns to get too carried away just yet.

Then days later Sven-Goran Eriksson was unveiled as Notts County's new director of football.

Even the old campaigners watched agog as the former England manager addressed the world's media at a news conference. Suddenly talk of aiming for the Championship was banished because Eriksson was going to take Notts County to the Premier League.

This is the same Notts County who only six years earlier emerged from a nightmare 534 days in administration. The same Notts County who had lurched from one relegation battle to the next and failed to muster a top-half finish in League Two since 2005.

That same Notts County were now heading straight to the top flight, with one of football's biggest names leading the way.

Our journey to the big time could not have got off to a better start.

With Eriksson watching on and a crowd of more than 9,000 packed into Meadow Lane, new signing Lee Hughes scored a hat-trick in a 5-0 hammering of promotion favourites Bradford City.

Being in the crowd alongside my family that day was one of my best memories as a Notts County supporter.

But none of it was real.

I didn't know it then but there were no wealthy backers from the Middle East. The untold millions didn't exist. It was not day one of Notts County's rise to glory.

The club, the players, Eriksson and every supporter who had dared to dream had been conned by a fraudster called Russell King and disaster was looming just around the corner.

More than a decade later I teamed up with presenter Alice Levine, who is also from Nottingham, and producer Nick Southall to investigate the incredible story of what really happened at Meadow Lane and much more besides, for a new podcast called The Trillion Dollar Conman, which is the latest addition to the Sport's Strangest Crimes series on BBC Radio 5 Live.

What we discovered was far darker than we could ever have imagined. It is a story that spans decades, taking us from Nottingham to North Korea, via Jersey, Bahrain and Dubai. It is a story of lies, greed, fast cars, fake sheikhs, false promises and lives ruined.

Of course, the fans knew nothing of any of this as they melted into town for a pint to catch their breath after that incredible Bradford game.

In fact, most supporters, myself included, weren't asking any questions about who actually owned the club and where the millions were supposed to be coming from, because Eriksson's arrival was all the proof we needed.

The Swede wasted no time in assembling his League Two fantasy football team. We interviewed him at length for the podcast and he told us he wanted to rebuild from the back - starting with a promising young goalkeeper by the name of Kasper Schmeichel.

Schmeichel played one season for Notts County before joining Leeds in 2010

Eriksson had recently been manager of Manchester City, where Schmeichel, the 22-year-old son of legendary Manchester United goalkeeper Peter, had failed to dislodge Joe Hart as the club's number one keeper.

He told us Schmeichel and his father took some persuading that dropping down four divisions was a good idea, but he eventually signed a five-year deal on a salary said to be worth up to £1.5m a year.

Soon Notts County were being linked with some of the biggest stars in world football, including legendary Brazil full-back Roberto Carlos and Portuguese winger Luis Figo, who had just announced his retirement at Inter Milan but was being tipped to reverse his decision and extend his career in Nottingham.

But most ludicrous of all was David Beckham, who at 34 was still an England international and at LA Galaxy.

On several occasions Beckham was asked by journalists whether he would be reunited with Eriksson at Notts County. He even appeared to add fuel to the fire by replying: "There's a few options, put it that way."

Then one of the finest defenders of the Premier League era walked through the door at Meadow Lane.

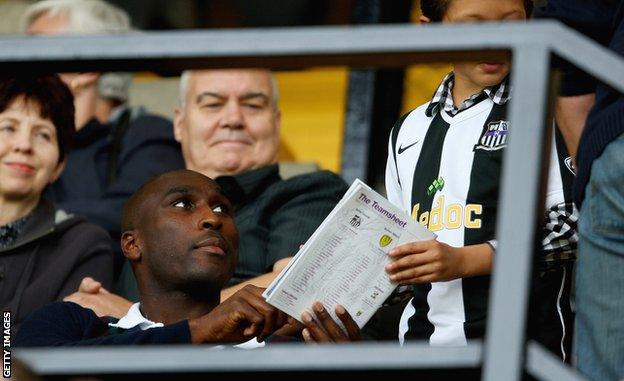

Sol Campbell might have been 34 and without a club after leaving Portsmouth, but only three years earlier he had scored in a Champions League final and played in a World Cup. He had won 73 England caps.

Campbell signs an autograph for a young Notts County fan in September 2009

It would take more than a month for Campbell to get fit enough to make his debut away at Morecambe, in September 2009.

My family and I were among more than 800 Magpies fans who made the trip to the Lancashire coast to watch what we expected would be a footballing masterclass by one of the best defenders the country had ever produced.

We would be disappointed.

Every one of the supporters I have spoken to agrees that Campbell had a shocker that day and Morecambe deservedly won 2-1, their first league victory of the season.

We all thought our miserable day out was just a blip, but days later the news broke that Campbell had walked out on Notts County.

Publicly, Campbell's sudden departure was quickly explained away by the club, but less than a week later another bombshell dropped, one that could not be so easily brushed off.

The Sun newspaper revealed a man called Russell King had been secretly at the heart of the Notts County takeover, and that he had served a two-year sentence for fraud in the early 1990s for falsely reporting his Aston Martin stolen to try to claim £600,000 in insurance.

The club said King was nothing more than a "strategic consultant" who had negotiated contracts on the club's behalf.

We now know that wasn't the case. Without ever having his name above the door, it was King who had orchestrated the takeover of Notts County and he was running the show.

But the story went wider. His takeover of the world's oldest professional football club was actually the centrepiece of one of the most outlandish scams in sporting history.

The Trillion Dollar Conman is available on BBC Sounds

King had managed to take over almost half a London investment bank by making false claims he was managing the sovereign wealth of the Bahrain royal family. He then took over Notts County using a bank guarantee from the same bank, which would later turn out to be worthless.

At the same time he had also established what he claimed was a huge international mining company and, incredibly, secured a deal with the North Korean regime to mine the country's vast mineral wealth, including coal and gold.

Eriksson told us that in October 2009 he was persuaded by King to go with him to North Korea, where regime officials asked him whether he could fix them a good group for the 2010 World Cup.

He tells us he struggled to make them believe this was out of the question.

With the North Korean mining deal in the bag, King went about making wildly false claims that this was one of the biggest mining companies in the world, with assets worth nearly two trillion dollars, and preparations were made to list the company on the stock market.

Experts who have tracked King's activities for years say he planned to use his ownership of Notts County - a club creating global headlines - as a means of driving interest in the stock market listing.

But King's lies began to catch up with him and his scheme ended in failure. Those close to the deal told us had he pulled off the stock market listing it would have been one of the biggest frauds in corporate history.

King fled to Bahrain, where he set to work on a new fraud which would culminate in the launch of a fake Middle Eastern version of the Financial Times. Police continued to pursue him and by 2019 he was in jail, convicted for a fraud he had carried out in Jersey a decade earlier.

Last year he was released from prison. We went to speak with him for The Trillion Dollar Conman podcast - to give him a chance to explain his side of the story. But he didn't want to.

Back in Nottingham in Christmas 2009, with King off the scene, Notts County were heading for serious trouble as months of wild spending caught up with them.

For the second time in a decade the club were in financial ruin and faced being closed down.

But with days to go before they were due in the High Court a local businessman called Ray Trew struck a deal to buy it for £1. He told us the debts he eventually uncovered exceeded £7m.

For the fans, myself included, this was a bittersweet moment. We were, of course, relieved our club had been saved (again) but Eriksson's departure following the takeover brought home to us that the dream really was over.

We all felt a collective hangover descend. We were left with six months of bizarre, surreal and often blurry memories to pick over. What on earth had happened? Did we dream the whole thing? We had no permanent manager and the team were listlessly drifting further from the top of the league.

Then in late February 2010 everything changed again with the appointment of Steve Cotterill as manager. Straight talking and supremely confident, Cotterill who is now in charge of Shrewsbury Town in League One, gave the whole club the jolt it needed to emerge from its collective malaise.

Notts County were seventh, 14 points behind leaders Rochdale when he took over. But they went on an outstanding run of 14 wins from 18 matches, scoring five goals in a game on four occasions.

They stormed up the table, eventually winning the title at a canter, 10 points ahead of Bournemouth in second.

The most remarkable season in Notts County's long and turbulent history ended with the League Two title. And this time it was real.

Who were the real Peaky Blinders?: Explore the origins of this mass gang movement

The rise of the American far right: Louis Theroux meets the movement's key figures