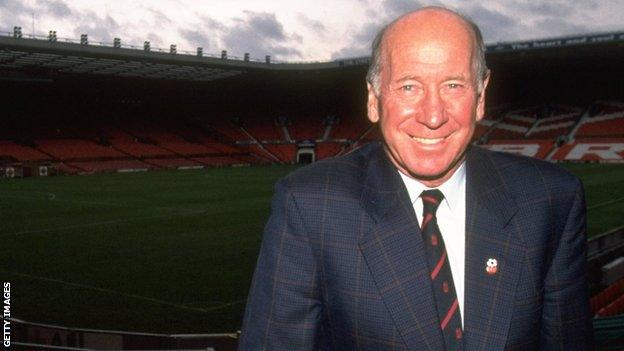

Sir Bobby Charlton: A personal account of meeting the Manchester United and England great

- Published

Sir Bobby Charlton won the World Cup with England in 1966

Of many chats I was fortunate to have with Sir Bobby Charlton down the years, the details of a couple have always stayed with me.

The first was during an interview, to coincide with the launch of his most recent autobiography, in 2007.

I was keen to learn about Charlton's development as a footballer, bearing in mind his mum, Cissie, was cousin to the legendary England forward Jackie Milburn, and sister to four other professional players, while his elder brother Jack had enough talent to win a World Cup.

His answer was briefer than I had expected.

"I never found football a bother, really," he said. "It all came quite easily."

The second was at the San Siro stadium in February 2010, when his beloved Manchester United beat AC Milan 3-2.

It was a very quick conversation in a packed lift - although it felt like he was the only person in it. He asked whether I would be going to that summer's World Cup in South Africa.

When I told him I was, he replied instantly: "You should go and see Nelson Mandela."

I said I doubted that would be possible. This time, the reply came back: "I'm sure he would [see you], he's really good. He always makes time for me."

With that, the lift doors opened, he was ushered away and I scurried off to whatever post-match activity was taking place.

Obviously, Charlton knew he was a very good footballer. He also knew his status - it was one of the reasons why he could appear standoffish to those he didn't know.

But to me, these stories showed it didn't live with him 24/7. Playing football was something he did because it was natural. In the moment, in the lift, he didn't see that what he was capable of on a football pitch opened doors that remain closed, locked and bolted to mere mortals, off it.

Pre-season tours tended to offer the best opportunity to speak with Sir Bobby.

I will never forget the first occasion. Portland, Oregon. First stop on United's 2003 trip to the USA.

There was the offer of a round of golf with some of the other journalists lucky enough to be on the trip but as I was not much of a player, I accepted the chance of speaking with Sir Bobby enthusiastically.

He told me about his footballing experiences in the United States, where he played twice for England - in 1959 and 1964.

His most vivid memory was from the second game, in New York, which was played at an athletics venue, when he went sliding over the touchline and into the long-jump run-up, which grazed his leg.

Despite sitting with him for half an hour, it was only when I returned to my room that I discovered he scored a hat-trick in the space of 21 minutes on his first trip, in Los Angeles, when he was 21.

In more than six decades since then, only Jimmy Greaves and Theo Walcott have scored hat-tricks for England at a younger age.

I have to admit, that first interview was not the most robust I have ever done. I spent a good chunk of time thinking how incredible it was that I was sitting opposite one of England's greatest ever players, that he had just bought me a coffee and how it all seemed so, well, normal.

Yet once he got out on club business for his beloved Manchester United, he became an ambassador in every sense of the world.

Charlton won three league titles, a European Cup and an FA Cup with Manchester United during 17 years at Old Trafford

I didn't speak to him the day I tagged along to a trip to an orphanage in Guangzhou. But to see him interact with the young Chinese children, who evidently had not been given the greatest start in life, was something to behold.

It was earlier in 2007 that I spoke to Sir Bobby on the phone about the other sporting love of his life, golf, and the faintly ridiculous dilemma he put himself in by "winning" a Mercedes thanks to his hole-in-one at Formby Hall Golf Club.

Charlton's problem was that if he accepted it, he would have to turn professional, which is a bit of an ask for a 66-year-old and would have meant the end of his social golf.

"I honestly don't know what to do," he laughed.

In the end, he didn't take the car. He donated it to the Christie Hospital in Manchester.

And I didn't get to meet Mandela, but I did have the amazing good fortune to sit at the back of the room when he met a United contingent, external during their tour of South Africa in 2006.

Charlton was the head of the club delegation in Johannesburg, in the unusual position of having to wait patiently while someone with greater status arrived.

Mandela was 88 at the time and his life must have been filled with such meetings. Yet it was clear from his reaction, both in the fondness of his greeting and the warmth with which he accepted a mounted photograph of Old Trafford from Charlton, that the affection between the pair was real and went both ways.

The picture taken of them both that day seems poignant as we mourn Charlton's passing.

With the sadness, solace comes from the knowledge that the impact during his life was a positive and lasting one, which will be spoken of by generations long after those of us who were fortunate enough to know him have passed on.