It’s 5:45pm on matchday in Gelsenkirchen and tram 302 is bouncing.

The 20-minute, five-and-a-half-mile journey to the Veltins Arena is the first sign of the raucous noise that awaits.

Kick-off for Schalke 04’s match against Nuremburg is still just under three hours away.

But homages to Schalke, in the form of stickers, graffiti and murals, are on almost every surface, surrounded by reminders of the region’s industrial heritage.

The stadium stands on a hill on the city outskirts and every entrance is packed with eager fans. An aroma of beer, bratwurst and cigarette smoke hangs in the air.

An hour before the action starts, the Nordkurve housing the Schalke ultras is full and loud.

By kick-off, there are 62,000 packed in and it is hard to hear a single thought.

This is the Schalke ritual, one that has played out in Europe many times.

Over the past 20 seasons, they have played in the Champions League eight times. In 2011 they reached the semi-finals, losing to Manchester United.

In 2019, their most recent campaign among the elite, they reached the last 16, losing to Manchester City.

But this is a different stage, with different stakes.

This is Bundesliga 2 - the German second tier. Schalke are fallen giants, hanging dangerously close to a second relegation in succession and, possibly, oblivion.

Despite recent assurances that their finances are holding up, the viability of the debt-saddled club as a genuine power is in doubt.

How did this colossus - the third biggest club in Germany in terms of members, with the third most league titles of all time - end up on the edge?

And is there any way back?

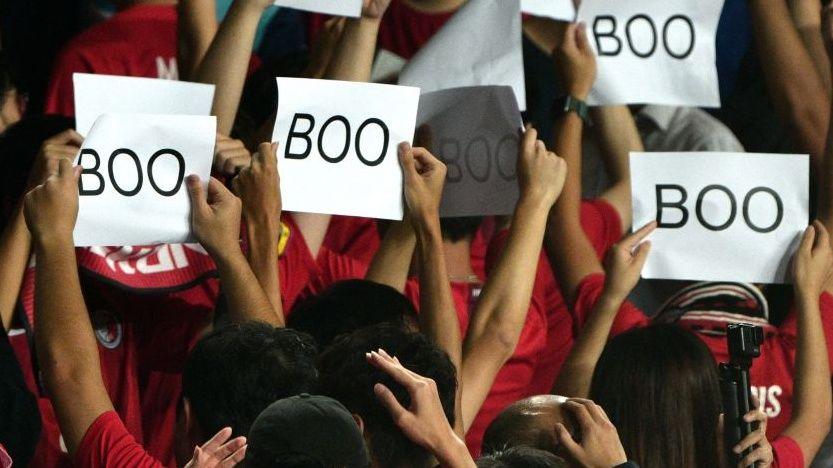

Schalke's players react after their relegation to the second tier was confirmed by a 4-2 final-day defeat by RB Leipzig in May

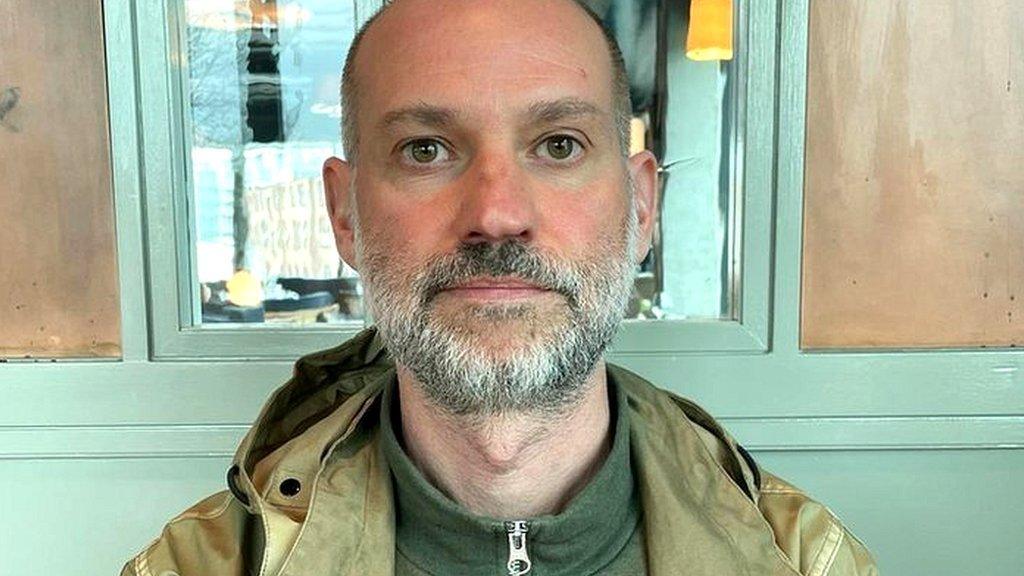

“Their fans are talking in apocalyptic terms,” says journalist Felix Tamsut, who writes about football fan culture for Der Speigel and others.

“You have crisis clubs in Germany, clubs going bankrupt, but I don’t think I’ve seen a club as big as Schalke talk in a way like their fans do. It’s shocking to see from a German football perspective.

“It is a huge club - about 160,000 members. That’s more than Real Madrid, more than a lot of big clubs in Europe. Schalke is the most extreme case of a club trying to live beyond its means.

“Having lots of fans doesn’t mean you have the money, but they spent like they did, thinking things would work out.”

In 2016 Schalke signed teenage Swiss striker Breel Embolo for a reported 25m euros (£21.4m). The deal was revealed to Schalke’s fans via a video message that suggested the club had seen off competition from Barcelona, Manchester United and Arsenal.

But three years later, after 10 goals in in 48 Bundesliga games, Embolo was sold to Borussia Monchengladbach for half the amount Schalke had paid.

Nabil Bentaleb, signed from Tottenham in 2017 for 19m euros (£16m), departed for free at the end of his contract.

Embolo and Bentaleb are just two examples of poor recruitment in recent years.

And not only have Schalke bought badly, but they have also sold poorly.

Key players such as Leon Goretzka, and academy prospects Sead Kolasinac, Max Meyer and Joel Matip, who should have represented good avenues for profit, left on free transfers.

A stretched balance sheet came under further strain as the Covid-19 pandemic choked off the income from gate receipts and dented the value of the Bundesliga’s television deal., external

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 brought an abrupt end to the relationship with Gazprom – the energy giant majority owned by the Russian state and the club’s main sponsor.

“Decisions have been made in the past that were totally wrong and have cost a lot of money,” Anja Wortmann, Schalke Supporters Club board member, tells BBC Sport. “The team they put together didn’t fit and didn’t play well. There was a ‘hire and fire’ culture for new coaches.”

Current manager Karel Geraerts, hired in October, is the 11th permanent Schalke boss in 10 years.

The swift series of pay-offs, hefty transfer fees, punishing interest rates on borrowed money and world events have taken their toll.

Schalke’s debts rose to 217m euros in 2021 and, while they have since reduced that figure, they are sorely missing the income associated with the top flight.

Breel Embolo (left) was one of a clutch of big-money buys who failed to work out

They are also without long-time chairman Clemens Tonnies. The 67-year-old billionaire, who made his money in meat processing and frequently plugged holes in the club’s finances with loans, was ousted in 2020 after 19 years at the helm.

His departure followed an apology for controversial comments about population growth in Africa as well as a Covid outbreak at his plant that sent local infections soaring.

The club he left behind are now five points and four places clear of the Bundesliga 2's relegation play-off spot. Below that lies the automatic drop.

Schalke's debts are such that the German Football Association (DFB) has granted them only a conditional licence, external for next season's third tier, noting a “liquidity gap” that must be bridged by the end of June if their finances are going to be ready for the reduced revenues outside the top two divisions.

If they are relegated and fail to meet the financial conditions imposed by the DFB, the punishment is automatic demotion to the amateur regional leagues.

The club have been granted an unconditional licence to operate in Bundesliga 2 in 2024-25 if they stay up.

Crucial games against the division's bottom two sides - Osnabruck and Hansa Rostock - followed by a final-day trip to mid-table Greuther Furth will decide their fate.

Amid the change and challenges, the stress and the spreadsheets, the fans have been the one constant.

“Being a Schalke fan is about more than just the game,” says Wortmann.

“It is meeting friends before the game; it is driving together to away games.

“The clubhouse is like a pub - we drink, talk and sing. It is a special atmosphere. In England you have a saying, 'You only sing when you’re winning’. Most of the German clubs are the same; Schalke is different.

“Forty thousand Schalke fans wanted to go to each of the last three away games. The three stadiums combined didn’t have the capacity.”

Schalke fans' commitment comes at considerable cost for many.

Gelsenkirchen has an unemployment rate of 12.6%, almost 10 percentage points above the rate in Germany. The closure of the region’s coal mines means jobs have ebbed away. But the pride remains.

Before every game the Veltins Arena is serenaded by ‘Das Steigerlied’ - The Climbing Song - celebrating the city’s mining heritage.

The players' tunnel at the Veltins Arena is designed to look like a mine shaft in honour of the area's historic roots in the coal industry

Tim Hoogland is a former Schalke midfielder who came through the academy, and is now the Under-19s assistant coach.

“You have to know the history of the club. The area is the Ruhr Valley, a region where the coal mines were,” he says. “You have so many different cultures; it is a melting pot. Different people came from Italy, Turkey, and Yugoslavia to work. It is a very hard-working area of Germany. Because the mines closed, the area is very poor.

“Some of the people of Gelsenkirchen and the surrounding areas only have this club. It is a religion for them.

“If Schalke were in the fifth or sixth division, the bond with the fans would only get stronger. It is where everyone comes together, passed down the generations. Everyone lives and breathes it.”

Tamsut agrees: “There is a saying, ‘Schalke will never disappear’. Even if the whole club has to be set up again, the fans will do it. The entity called Schalke is way beyond any person; it lives in the hearts of so many.”

One of them is the captain of a rival team. Timo Becker, who leads Bundesliga 2 promotion-chasers Holstein Kiel, is a former Schalke player and a current fan. He has been known to play for Holstein Kiel on an afternoon and then stand on the Nordkurve alongside the Schalke ultras in the evening.

“Schalke is what people have in common,” says Wortmann. “You can be a doctor or be unemployed and it doesn’t matter. We call it kleinster gemeinsamer nenner (the lowest common denominator).

“People don’t know Gelsenkirchen, but if you say Schalke they recognise it.“

The famous nights in Europe that helped forge that reputation feel a long way away now.

The run to Old Trafford and the last four of the Champions League was 13 years ago this week.

One of Hoogland’s personal favourite memories from that era – his goal against a Real Madrid side featuring Cristiano Ronaldo, Gareth Bale and a host of galacticos – was a decade ago.

Hoogland (far left) celebrates his goal at the Bernabeu in 2014, but Schalke lost 9-2 to Real on aggregate in the Champions League last 16

“We created lifelong memories as a team,” he smiles. “I was injured for a lot of those Champions League games but, coming through the youth academy, I saw it from a fan perspective, watching historical players like Raul and Klaas-Jan Huntelaar. Schalke was always in my heart.

“The Champions League atmospheres were amazing. The semi-finals against Manchester United, the game in Madrid when I scored, were great.”

Hoogland is adamant that the roots for Schalke’s recovery are in their tradition of homegrown players.

“There is nothing as important as the academy for Schalke, in the past and the future,” he says.

“The amount of academy players who came through - Manuel Neuer, Benedikt Howedes, Mesut Ozil, Julian Draxler - all were in Germany’s World Cup-winning team in 2014 and started at Schalke.

“There have been lots of others. Joel Matip has been at Liverpool for nearly a decade, [Bayern Munich forward] Leroy Sane, [former Arsenal defender] Sead Kolasinac, [West Ham defender] Thilo Kehrer - so many great players.

“It is brutally important to bring in academy players.”

Goalkeeper Manuel Neuer was born in Gelsenkirchen and joined Schalke aged five before progressing to the first team and leading them to the Champions League semi-finals in his final season before a move to Bayern Munich

Off the field, the route forward is less clear.

In Germany the 50+1 rule, which guarantees that members own the majority share in clubs, is a point of pride. Protests aimed at protecting it have been common and widespread among clubs.

Some Schalke fans, though, feel that the club’s situation is so dire it is necessary to dilute fan control in favour of more investment. The return of shamed former chairman Tonnies has also been raised as an option.

“We have discussions among the fans in the last few years,” says Wortmann. “People say they want Tonnies because he has the money and he can help. The ultras say he is responsible for the current situation. He was the king. He pulled the strings. Everyone did what he said.

“Among the fans, we aren’t as united as it seems in the stadium. During the game everyone is supporting the team.

"Some fans don’t want 50+1 rule; they want the club sold to investors. You can see how much it means to the people. They fight, but it is with passion.”

Wortmann believes that loosening the rules to allow a cash injection into Schalke is short-term thinking. For her, the existing rules keep the playing field more level and the gradient back to the top more manageable.

“Union Berlin are the best example,” she says. “They reached the Champions League this season with not much money. Bayer Leverkusen won the championship. Everyone who is not a Bayern fan is happy about that.

“In Germany it is possible with a team that is quite cheap to challenge. We should stick to the 50+1 rule.”

A 2-0 victory over Nuremberg means the early-hours post-match tram back into Gelsenkirchen is just as lively.

The immediate future is beginning to look a little more secure. For now, anyway. Whatever is next, in its darkest hour Gelsenkirchen is clinging on to its soul.

As the saying goes, Schalke will never disappear.

This year marks 100 years since Westfalia Schalke, founded in 1904, changed its name to FC Schalke 04

Previously on Insight

- Published22 April 2024

- Published16 April 2024

- Published12 April 2024

- Published11 April 2024

- Published9 April 2024