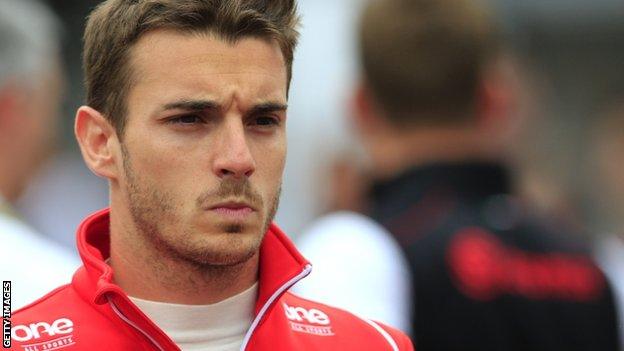

Jules Bianchi: What lessons can F1 learn from Japan crash?

- Published

Bianchi underwent surgery on Sunday and was then expected to be placed into intensive care.

The accident during the Japanese Grand Prix that left Marussia driver Jules Bianchi in hospital with severe head injuries is an illustration of the unsolvable and sometimes terrible paradox at the heart of motor racing.

No-one wants to see racing drivers hurt, and yet it is an inescapable reality that the very possibility of it is a part of what makes Formula 1 such an intoxicating draw for its participants and the millions who watch it around the world.

It has been 20 years since the last driver fatality at a grand prix, when the loss of Ayrton Senna kick-started a renewed drive for greater safety that continues to this day.

Yet all the drivers know that they are risking their lives every time they zip up their fireproof overalls, strap on their helmets and head out on to the race track to do what they love. It's an adrenalin fix that those who have experienced it tell you is like nothing else on earth.

Risk is part of the challenge, inherent in why drivers are revered, in the same way people admire the astronauts who went to the moon. They are doing something ordinary mortals could not - and would not - do.

What they do out there is beyond the bounds of comprehension of ordinary people: a combination of balance, feel, dexterity, skill, judgement and extreme levels of both bravery and physical fitness.

The sense of taking man and machine to the limits of the laws of physics and human capability is at the heart of the appeal of F1. Top drivers are the best in the world with the most advanced, challenging and fastest cars science can produce within the restrictions imposed on them by the rule makers.

Those restrictions are there because the people who run F1 are fully aware of the dangers, and want to reduce them as much as possible while maintaining the essence of the sport.

How to strike that balance is a debate played out, in rather less sombre circumstances, at virtually every race during a grand prix season.

Crew members of Marussia driver Jules Bianchi push his car to the grid before the start of the race

Just two races ago, in Italy, there was a discussion about whether safety changes to the famous Parabolica corner - turning a gravel run-off into an asphalt one - had removed its challenge.

And the contradiction organisers are battling with was there again on Sunday.

There were the usual complaints about the race starting under the safety car after heavy rain, only for conditions to have improved so much that drivers were in for the lightly treaded 'intermediate' tyres within a couple of laps.

Yet later, after Bianchi's accident, there were criticisms that the race had not been stopped sooner when the rain came down more heavily.

At Suzuka, where Bianchi crashed on Sunday, this contradiction is inherent in the track itself.

The drivers love the place because it is what they call an "old-school" circuit, an extreme driving challenge where the risk of an accident is much higher than at more modern circuits, which are often criticised as being sanitised and soulless.

Suzuka is often likened to a roller-coaster, but this is a roller-coaster where it is all too easy to come off the rails. Run-offs are small, and mistakes are often punished by impact with a barrier and a damaged car, rather than a second or two lost running wide into a vast expanse of asphalt.

For the drivers, the jeopardy inherent in Suzuka is not a bad thing, and for all the greater risk of a crash, very few drivers have been injured there. The run-offs may generally be smaller than those elsewhere, but they tend to do their job.

In any case, that is not why Bianchi, a popular and promising talent whose career is only just beginning, is in intensive care in the Mie Prefectural General Medical Center in Yokkaichi.

Jules Bianchi |

|---|

Born: 3 August, 1989 in Nice, France |

Races: 34 |

Highest finish: Ninth |

The inquest into what went wrong, and how such an incident can be avoided in the future, has already started, and it will be long and detailed.

Although there was a lot of debate over the Japanese Grand Prix weekend about the timing of the race, with typhoon Phanfone approaching the mainland, the fact it was wet was only a circumstantial factor.

And debates about the timing of the race are essentially irrelevant. Whenever it was held on Sunday, it would have been wet; bands of rain of varying degrees of intensity passed across the track throughout the day.

Fundamentally, Bianchi's accident - and, more importantly, the fact that he suffered his awful injuries - was a combination of what world champion Sebastian Vettel called "a very unlucky place and unlucky timing".

Bianchi went off at the Dunlop corner, a fast uphill left-hander, which essentially forms the very last part of Suzuka's Esses, regarded by many drivers as the most demanding section of track in the world.

The run-off at Dunlop was extended a few years ago, but it remains relatively small in modern F1 terms - the tight confines of the land around Suzuka and the layout of the track mean it would be hard to make it any bigger than it is. So if a driver spins off at Dunlop, he is going to hit the impact-absorbing barrier, as Sauber's Adrian Sutil did the lap before Bianchi's crash.

Medics at the scene treat Bianchi

What will almost certainly be the central discussion point in the analysis of what went wrong was that Bianchi's car hit a tractor vehicle that had been sent out to recover Sutil's car. Pictures suggest the impact may have torn the roll-hoop off Bianchi's car, which is there to protect the driver's head.

There is ongoing research into the use of extra cockpit head protection in F1 cars. Officials say it is inevitable this will be introduced once a suitable way to do so has been established. Which is no easy task.

But this is aimed at protecting drivers' heads from flying wheels and it is doubtful it would protect a driver from an impact with a tractor or a crane.

As they worked on Sutil's car, marshals were giving the most extreme form of warning to drivers before a race stoppage - double waved yellow flags.

Despite that, Bianchi lost control because his car, like Sutil's, aquaplaned. That means it effectively floated on top of the water on the track, which can easily happen with an F1 car. In such circumstances, there is nothing a driver can do.

There was a remarkably similar incident at Suzuka 20 years ago, when McLaren driver Martin Brundle spun off a couple of hundred metres further along the track from Bianchi's incident.

Japanese GP: Lewis Hamilton sad after 'anti-climax' win

At the time, Brundle narrowly missed a tractor unit, and he has talked since that he thought it might be curtains for him. Instead, he hit and badly injured a marshal, who was recovering the car of another driver who had gone off a few minutes earlier.

Despite that, cranes continue to be used occasionally to recover crashed cars in F1 and until now no-one really thought anything about it.

The combination of circumstances at Suzuka - worsening rain, fading light, a small run-off area, a driver losing control despite waved caution flags -highlighted the risks.

As always, though, it is a complicated issue.

It is easy to say the vehicle should not have been there. Yet cars need to be recovered somehow, because hitting a stranded racing car at speed is dangerous in itself.

So there will surely be discussions as to what can be done about this - perhaps putting a safety car out to neutralise the race before a recovery vehicle is used, or finding some way to make them less dangerous things to hit.

Driving on the edge - the limits of Formula 1 cars | |

|---|---|

Cars can develop 3.5g lateral cornering force (three-and-a-half times their own weight) through aerodynamic downforce. | Drivers can sweat off anything up to 3kg of their body weight during the course of a race due to intense heat in the cockpit. |

It means that, theoretically, at high speeds, cars could drive upside down. | Cars must weigh a minimum of 690kg following rule changes at the start of 2014. |

Formula 1 car engines are 1.6L V6 turbo charged - producing around 600bhp. | Drivers can utilise an additional 160bhp from an Energy Recovery System (ERS). |

It has been five years since a driver was as seriously injured as this in an accident at a grand prix. That was when Felipe Massa was hit on the helmet by a suspension part from another car in Hungary 2009.

"We get used to it when nothing happens and then suddenly we are all surprised," said Mercedes non-executive chairman Niki Lauda, a man who came close to death in a fiery accident in the 1976 German Grand Prix and still bears the scars.

"But we always have to be aware that motor racing is always dangerous - and this accident today is a coming together of various different things.

"One car goes off, the truck comes out and the next car goes off and this was very unfortunate.

"There could be a lesson learned that in the difficult conditions of today, in the race, that [the governing body] could have acted differently."

Safety has come a long way in motorsport, and the FIA is constantly striving to improve it.

But the unfortunate reality of motor racing is that sometimes lessons are learned the hard way.

- Published5 October 2014

- Published18 July 2015

- Published5 October 2014

.jpg)

- Published5 October 2014

- Published5 October 2014