Allan McNish column: Is Formula 1 losing its soul?

- Published

The German Grand Prix, won by Michael Schumacher in 1995, has a rich heritage but was missing from this year's Formula 1 calendar

In the last week, there have been media reports questioning the future of the British Grand Prix and the announcement of a 21-race calendar for the 2016 season.

In combination with this weekend's stop on the schedule - the Russian Grand Prix - it is a reminder of the direction in which Formula 1 appears to be headed.

More of the historic European events that reflect the essence of racing are disappearing off the F1 schedule to be replaced by big state-funded projects that fail to deliver the same kind of racing and atmosphere.

That the F1 schedule is in a state of major flux is without doubt; whether that is necessarily a good thing is a different matter.

Does F1 need European races?

Europe is where F1's heart is - in terms of the teams, the drivers and its core audience. And yet the future of a number of countries as race holders is in doubt.

Silverstone has a contract to stage the British Grand Prix that lasts until 2026, with the first break clause after 2019, but that has not stopped questions about its future., external

Monza in Italy, the oldest race of them all, has one more year on its deal and there has so far been no agreement on the financial conditions for a new one.

Germany dropped off the calendar this year because of financial problems at the Nurburgring and there are doubts about its long-term future after a poor crowd at the other venue, Hockenheim, in 2014.

These are all circuits with a long and rich history. Nurburgring has held 40 grands prix; Hockenheim 34; Silverstone 49. Monza has been on the grand prix calendar almost uninterrupted since 1922.

A sell-out crowd of 140,000 saw Lewis Hamilton win this year's British Grand Prix

These race tracks inspire generations - of teams, drivers and fans. I'll certainly never forget my first visit to the British Grand Prix at Silverstone.

It was 1987, and the great battle between Nigel Mansell and Nelson Piquet. I was standing on the grass bank between Club and Abbey corners - so I could not see Mansell re-take the lead with his famous dummy pass into Stowe. But I knew it had happened because of the roar of the crowd.

I was just a kid who had just got his driving licence for the road - but it has stuck in my head ever since.

It was the same when I went to Monza for the first time, when I was racing in Formula 3000. There was a Formula Three race on the same bill, and they were running without rear wings because of the long straights. It was so fast and different to any other track - the endlessly long straights, fast chicanes, threading a needle.

Same at the Nurburgring, when I first went there in 1988, listening to James Hunt talking about how the new circuit was nothing like the old one.

The point is, all those venues have real stories behind them, stories based on history and character, famous corners that we still call by a name not a number, something the new tracks don't have - and in a lot of cases will never have.

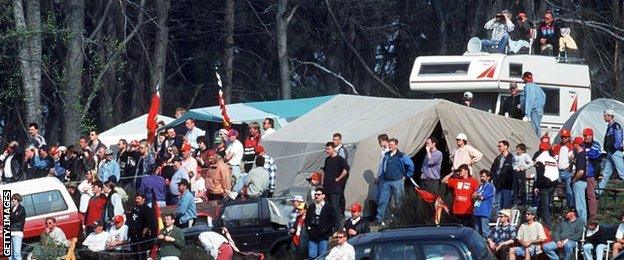

Thousands of fans flock to European races for the relaxed atmosphere and many camp on the outskirts of circuits

Many of them are funded by governments, looking to promote themselves globally for whatever reason, and when the money runs out, the race stops, because the tracks cannot make it on their own. And with them goes any chance of building a motorsport culture.

Turkey, South Korea and India are three countries that have built state-of-the-art F1 tracks in the last decade, only for the races to drop off the calendar after just a few years, without leaving any long-lasting impact - whether it be by those countries on F1, or F1 in those countries. Some of the more recent events could well go the same way.

What happens if the European races go?

In the past, the historic races were protected by the Concorde Agreement, the contract that bound the three parts of F1 together - the teams, the governing body and the commercial rights holder.

That clause was there because it was realised how important it was to maintain that tradition.

But the Concorde Agreement has lapsed and a new one has yet to be signed, so there is now no protection, no requirement for the European races to be kept on the calendar.

Apart from 1980, Monza has hosted the F1 Italian Grand Prix every year since 1950

If any major European country loses its grand prix, it's almost inevitable that, eventually, that country will lose its foothold as a place that is strong in motorsport - even Britain. And without that, the conveyor belt of new F1 drivers dries up, too.

In my view, the historic grands prix are the heartbeat of the sport.

Without Silverstone, Spa, Monza, Monaco and Germany, F1 would lose a direct link back to its heritage, and with that would go the context for the achievements of the present and the future.

There's an old song called You Don't Know What You've Got (Until You Lose It). The warning signs are there.

It would be utterly wrong to lose those races for the sake of a few quid here or there.

Of course, F1 needs an income, but you have to wonder whether money is now the only guiding factor in decisions about the future of the sport.

It's about time those in charge thought about controlling that, and considered a bit more carefully what the F1 calendar should look like - and what it will look like in five years' time.

Many fans have embraced new circuits - others, such those seen here at the Shanghai International Circuit in China, are yet to see a "classic race"

Too many races?

The 21 races next year, external will represent the longest season there has ever been. It is almost one grand prix a fortnight over the entire year - but crammed into a period of less than nine months.

Of course, it is considerably fewer grands prix than there are Premier League football matches, or even Nascar stock car races. But both those events take place over a much smaller geographical area, so it is easier to handle, both logistically and in terms of the toll it takes on those involved.

The further away a grand prix, the greater the adverse effect on the teams, and particularly the mechanics, whose body clocks are all over the place jetting to and from far-flung places.

But the effect it has on the participants is only one aspect of this longer season.

Some would argue 21 races is too many - that a grand prix should feel special, and the more there are, the less noteworthy each one becomes.

Others would say that the more races F1 has, the more money the teams get and the more exposure the sport gets on a global basis - especially if it is going to new territories. And getting it out there is crucial for F1's future health.

Are the races in the right places?

The F1 teams are all based in Europe. But 11 of the 21 races next year are outside Europe - and that number rises to 13 if you include the Russian race in Sochi and the new event in Baku in Azerbaijan. Both of which, although technically European, are far enough away geographically for them to be considered long-haul races.

F1 boss Bernie Ecclestone (right), seen here with Russian president Vladimir Putin (centre), has signed a five-year deal worth an estimated $250m to stage the Russian Grand Prix in Sochi

And whether a Russian Black Sea resort and the capital of Azerbaijan are technically European or not, they are well outside the traditional motorsport base of western Europe, in which there will be only eight races next year.

Ten years ago, there were 19 races, with 11 in western Europe - three of which are not around any more, in terms of a second race in Germany and Italy and France.

The direction the sport is heading in is very clear from that shift over what is, after all, a relatively short space of time.

Globally, there is a changing dynamic for sports at the moment, in which Europe looks to be declining in terms of its ability to fund big events and the influence of other parts of the world is growing.

I'm not in any way against new venues, but I do feel F1 has to be careful not to lose its core values, and about adding in yet another race without weighing up the impacts of that, both in the short and long-term.

- Published6 October 2015

- Published6 October 2015

- Published6 October 2015

- Published18 December 2015

- Published2 November 2018

- Published26 February 2019