Formula 1 halo: Will sport put safety before style?

- Published

- comments

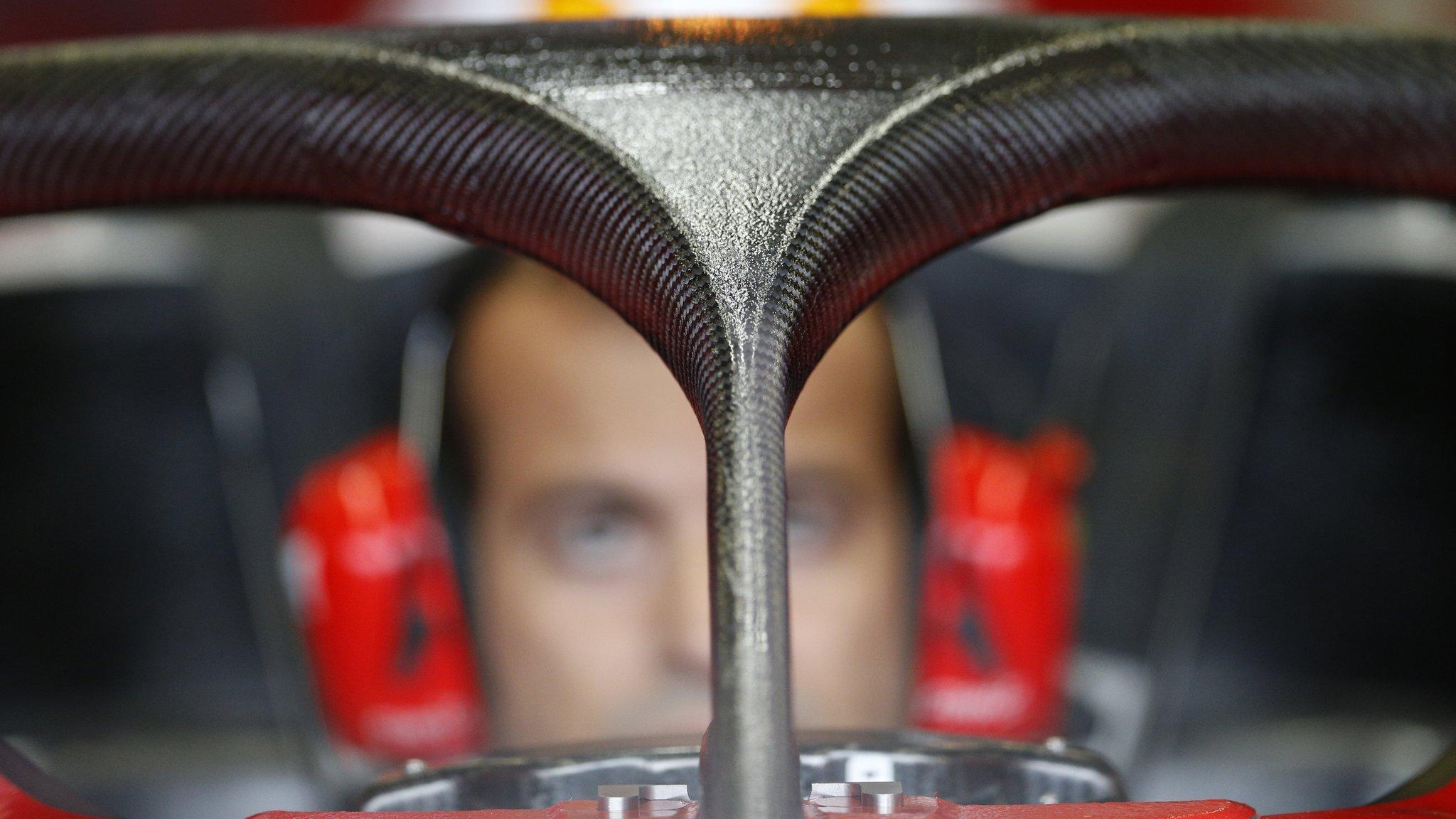

Red Bull and Ferrari have both run trials of the controversial 'halo' cockpit design

The introduction of the controversial new 'halo' cockpit head protection system into Formula 1 hinges on a critical meeting to be held on Thursday.

The 'strategy group' of the sport's leading figures is having its latest meeting ahead of this weekend's German Grand Prix and the 'halo' is one of the main items on its agenda.

The key decision is whether a device aimed at addressing the single biggest area of vulnerability for drivers should be adopted in 2017.

On the face of it, the answer might appear simple. The halo undoubtedly improves safety. It exists. It has passed all the tests. It does what it is meant to do. And the 2017 cars are being designed for it.

How have F1 cockpits evolved?

But the debate that has raged about it - and will be addressed by the strategy group - goes beyond that, into aesthetics and the central philosophy of what F1 should be, and be seen to be.

Why is the halo being introduced?

The idea of the halo was initially proposed by Mercedes, and has been further developed fundamentally by Ferrari under the aegis of governing body the FIA, to address the single biggest safety failing of F1 cars.

Safety has improved dramatically and consistently over the last couple of decades, since the death of Ayrton Senna in 1994 led to a renewed and more focused approach to the issue.

The cars have got stronger, safety systems have improved and the biggest risks have been removed from circuits. But one major anomaly has remained - the driver's head sticks out of the car, and is protected only by a helmet.

Jules Bianchi died nine months after suffering severe head injuries in a crash at the 2014 Japanese Grand Prix

The risks are obvious - flying debris can hit the driver's head; an inverted car can land on a wall upside down; and on and on.

These sorts of incidents have been the central cause of all the major injuries and deaths that have occurred in forms of motor racing in the last few years.

Jules Bianchi dying after hitting a recovery vehicle at the 2014 Japanese Grand Prix

Justin Wilson suffering fatal injuries from flying debris in an IndyCar race last year

Henry Surtees, external killed by a flying wheel in Formula Two in 2009

Maria de Villota dying in 2013, 15 months after hitting a low loader in an F1 test

Felipe Massa, external suffering a fractured skull after being hit by a piece of suspension from another car in 2009

Several other lower-profile incidents and near-misses of cars mounting other cars, such as Romain Grosjean's flying Lotus narrowly missing Fernando Alonso's head at the start of the 2012 Belgian Grand Prix, or cars upside down on barriers and on and on, some in F1, some in other categories.

So rule makers set themselves a simple task - come up with a device that deflects large objects that could otherwise encroach on the cockpit.

The halo is the answer - made of titanium, in an oval, or halo, shape above the driver's head, secured at three points, one directly in front of him and two at the back of the cockpit.

If it is adopted, all teams will use a single design, and it is not expected to have any effect on the racing.

As an engineering solution, it is elegant and effective. But not everyone is happy about it.

Who's for it?

The drivers, through their union the Grand Prix Drivers' Association, have made it clear they would like to see some form of additional head protection introduced as soon as possible.

They recognise the limitations of the halo - it is unattractive, some would say ugly; looks like a bit of an after-thought - but also its strengths - it is very effective at doing what it was designed for. For them, it works, it is available, it is the best system for the moment, so introduce it.

There have been some dissenting voices - among them world champion Lewis Hamilton, who in March called it "the worst-looking modification in F1 history".

Hamilton has accepted the halo design but added it would be good if "there is any way to make it look a little better"

Even Hamilton, though, has now come around.

The drivers were given an extensive presentation on the effectiveness of the halo by the FIA at last weekend's Hungarian Grand Prix, aimed also at addressing their concerns about visibility and its potential downsides in specific types of incidents.

The FIA's research shows how in almost every single incident in which a driver's head was vulnerable in the last 20 years, the halo would either have reduced his risk of injury, or made the situation no worse. And that visibility, while affected to a degree, was nowhere near the issue they thought it was.

Afterwards, the shift in Hamilton's opinion was dramatic.

The halo, he said, "doesn't look like it belongs on an F1 car". But he added: "I paid close attention. I take safety very, very seriously.

"It can still be improved so at some stage we will have canopies and then it will be 100%. I don't think we can ignore it and if there is any way to make it look a little better (that would be good) but it's a safety thing that we all have to accept."

Who is against it and why?

Those objecting to the halo recognise its value in improving safety, but object to it on grounds of aesthetics, because they feel it undermines the spirit of F1 as an open-cockpit formula, and because it feels to them a little rushed, like a halfway house to a better thought-out system.

Red Bull team principal Christian Horner has already said he is going to vote against it, saying it is "an inelegant solution to the problem it is trying to deal with". His team had its own proposal, the so-called 'aeroscreen', which they felt looked better, but it failed the FIA's tests.

F1 commercial boss Bernie Ecclestone has not yet expressed a view but is said by senior sources to be campaigning behind the scenes fairly vigorously against the halo.

And two other team bosses on the strategy group, Mercedes' Toto Wolff and Willams' Claire Williams, also have doubts, although are reserving their position for now.

Wolff says he wants to see the FIA's presentation before he decides.

"Whatever can be done for the safety of the drivers needs to be done, even if it looks disgusting," he said. "I don't think it looks F1. I don't think it makes the sport and the cars and the drivers appear spectacular.

"But all that doesn't count because safety goes first and we are going to have a discussion about all the safety aspects of the halo - is it the safety tool that we need in order to protect the drivers more?

"We need to look at all the studies that have been done and discuss them and come to a decision that either it is a good thing or it is not where it should be yet, or we don't like it.

"I haven't made up my mind because I want to hear the other arguments as well."

Is the strategy group the final step?

The aesthetic look of the halo design doesn't concern Sebastian Vettel, who has tested the device this season

Many of the drivers share the reservations about aesthetics and the purity of F1. But by and large they have little time for them within the bigger picture.

Four-time champion Sebastian Vettel, a director of the GPDA, said: "It is not made for looks, is it? The outcome was positive in all the scenarios the FIA went through. It is now up to the FIA to push it through.

"You can debate about the advantages and disadvantages of the strategy group but overall we need to trust the results of the FIA and their findings and on balance it always looked positive."

It's not that simple, though.

The strategy group voting system is complex. It comprises Ecclestone, FIA president Jean Todt and the Ferrari, Mercedes, Red Bull, McLaren, Williams and Force India teams.

Ecclestone and Todt have six votes each, the six teams one each; items need a two-thirds majority to pass. So the vote is on a knife-edge.

Todt has not made his position clear publicly, but sources close to him say he wants to see the halo introduced, even if he sees the problems others do.

His F1 director, Charlie Whiting, is most definitely pro-halo, but acts in the strategy group only in an advisory capacity.

Whiting dismisses aesthetics concerns as peripheral, saying that once the halo is painted the same colour as the cars, many concerns will fade, and that within a few races everyone will accept it. As they always do with such innovations, such as high cockpit sides.

The FIA has the right within the rules to force it through on safety grounds, but Todt has told his fellow strategy group members that he would rather go with the consensus.

What if F1 decides against the halo?

F1 has greatly improved its safety record since the death of Ayrton Senna in 1994

But if the strategy group votes goes against the halo, F1 could find itself in a thorny situation.

Now that the halo exists, what happens if it is not adopted and then someone is killed next year in just the sort of accident the halo is designed to prevent?

If it's one of the less high-profile drivers it would be bad enough - the FIA and F1 would be open to lawsuits. The damages could be very serious. Uncomfortable questions would be asked.

Imagine if a global superstar such as Hamilton, Alonso or Vettel were killed. Beyond the legal and financial ramifications - which would already be enormous - the public image impact would be potentially seismic.

Senna's death in 1994 raised questions about F1 at the highest levels in governments across the world. For a time, the very future of F1 seemed at stake. Things only quietened down when Todt's predecessor Max Mosley started a very public campaign to improve safety and made it clear that something was being done.

In this scenario, though, the sport and its bosses would be seen to have been wilfully negligent and who knows what would happen as a result.

Will anyone on the strategy group really, when it comes down to it, take that risk?

Subscribe to the BBC Sport newsletter, external to get our pick of news, features and video sent to your inbox.

- Published24 July 2016

- Published28 May 2016

- Published25 July 2016

- Published18 December 2015

- Published8 August 2017

- Published13 May 2016

- Published26 February 2019