Divorce, fire & 22-hour days... the reality of life in Formula 1

- Published

Kenny Handkammer was there when Jos Verstappen's Benetton was engulfed in flames during refuelling

The life of those in the Formula 1 circus can certainly appear glamorous. And, for the most part, it is - homes in Monaco, lavish parties and private jets a part of everyday life.

But for F1's mechanics - the lesser-known faces of the paddock - life is very different. They are more likely to live in Mansfield than Monaco, while very long hours and airport queues are part and parcel of the job.

It's a career fraught with danger. They've received electric shocks, taken whacks to delicate parts of their bodies and almost been run over, all in the line of duty.

Plus, it makes being in any kind of long-term relationship very tough.

Yet it can be incredibly rewarding.

'Retired' at 30… or divorced

With 21 races on the F1 calendar - not to mention testing - team personnel can find themselves away for almost half the year. No surprises, then, that maintaining a relationship can be difficult.

Most mechanics are in their thirties, with the majority then moving on to something that offers a better work-life balance. But among those who stick with it longer, divorces are commonplace.

Kenny Handkammer spent 25 years in Formula 1. He was front jackman when Jos Verstappen's Benetton was famously engulfed in a fireball in 1994 and was Red Bull's chief mechanic during Sebastian Vettel's title-winning era. He knows better than most what it takes to survive in the job.

While it is economy class travel for the majority of mechanics and other team personnel, many of the drivers have their own way of getting to races - Lewis Hamilton favours the private jet

"You have to have a very, very understanding partner," he tells BBC Sport.

"If you have always done it and then meet someone and they are aware of your travelling it is a bit easier but if you are in a relationship and then decide you want to go off to F1 races it can be tougher.

"A lot of people struggle with it. To do this job you have to be so committed and focused. You can't half do this job. You have a guy's life in your hands and the drain on you means you need to be 100% committed.

"It is a bit better than it used to be. In the old days it was harder. You get back and you are tired and that doesn't help any relationship. You'd also get up and not be in the best of moods, depending on the weekend you'd had."

You see the hotel and the circuit. That's it

Airport-hotel-circuit-hotel-airport. That's pretty much all a mechanic sees during a Formula 1 weekend

Travelling to Australia? Fancy a bit of sightseeing? That's out of the question for F1 mechanics.

While many drivers are whisked to and from countries in private jets and helicopters, it is airport queues and economy class for those tasked with keeping the cars in shape.

"We see very little of the country we are in," says Handkammer.

"On the first day you might get a little bit of time, but once you start work all you see is the circuit, the route to the circuit, and the hotel. We could be at Silverstone for every race because we pretty much don't see anything but the circuit."

Who'd be a mechanic? |

|---|

Salaries for mechanics are typically around £30,000-£60,000 per year. Sebastian Vettel is believed to be the highest earner in F1, with his annual salary standing at around £40m |

Fire burns, being hit by cars, electric shock, heat exhaustion, foot blisters and chronic fatigue are all dangers of the job |

All or nothing. Mechanics are often away for around 180 days of the year and working for around 12 hours a day |

Generally the mechanics will arrive at a circuit on Wednesday afternoon to get the cars and equipment set up. Thursday is then spent doing systems checks before a race weekend officially begins with Friday practice.

From then on, the mechanics are working flat out from dawn until dusk. If they are lucky they will get four or five hours sleep a night, although it was much worse before a curfew - that prevents team personnel being at the circuit for six hours overnight - was introduced in 2011.

"A Friday would normally be a 21-22 hour day," says Handkammer. "We would do that on the Fridays and the Saturdays in the old days. You really felt it.

"You are on your feet for those 22 hours. You'll maybe stop for 20 minutes if you are lucky. Sometimes, if there is work from the night before, you would skip breakfast and maybe grab a sandwich at lunch and then you might get 20 minutes or so downtime in the evening.

A Sauber mechanic was taken to hospital in an ambulance after being hit by the car of Japanese driver Kamui Kobayashi in the pits at the 2012 British Grand Prix

"Every mechanic suffers from sore feet. It doesn't matter how good your trainers are, people are not designed to be on their feet for 22 hours a day. It is pretty brutal."

Even between races there is very little downtime.

"If there's two weeks between races then we would get back from one race on the Monday after stripping the car on Sunday," adds Handkammer.

"We'd have a day off on Tuesday and then back in on Wednesday. It would then be a normalish week - hopefully finishing the cars on Friday and then getting the weekend off. We would then fly out to a race on the following Wednesday.

"Back-to-back races are different. You'd strip the car Sunday and pack up 50 tonnes of equipment and then fly out Monday to the next venue and begin work straightaway."

Fireball to the face? The ever-present threat of danger

Jos Verstappen had "a bit of a burnt face" but was otherwise OK as he and the Benetton mechanics escaped serious injury when fuel caught fire during the 1994 German Grand Prix. Handkammer is the mechanic in colour on the left

Formula 1 is a profession where not a single second can be wasted. Mistakes can and do happen, while risks are sometimes taken to get the edge over other teams. The outcome can be dangerous for both driver and mechanics.

One of the most frightening and memorable incidents of something going wrong was Jos Verstappen's pit stop fire during the German Grand Prix in 1994.

Refuelling during a race was still permitted and on this occasion a sudden spurt of fuel being added to Verstappen's Benetton resulted in a dramatic fireball that engulfed the whole car, including the Dutchman and his crew. Amazingly, everyone escaped serious injury.

"Jos was good about it," remembers Handkammer. "He had a bit of a burnt face but he was great. He was laughing in the end.

"What was tough, though, was the fact Michael Schumacher [Verstappen's team-mate] was due a stop soon after.

"Some of the guys had gone off to hospital already and I needed to find people, but some were saying they didn't know if they could do it.

Taking one for the team. A Lotus mechanic with an icepack on his groin after Romain Grosjean overshot his pit stop at the 2015 Spanish Grand Prix

"It was not needed in the end because Michael's car stopped with a fuel problem but in a way that was worse. It meant we had two weeks of downtime going through what happened, you were just asking: 'Do I really want to be stood in front of a car? Do I really want to be putting fuel in it?'

"If we had done that second pit stop straight away, it would have got it out of the system a bit."

The drivers - a good bunch?

Rarely will F1 mechanics find themselves in the limelight. If they are, it will be because of a big mistake made during a pit stop or if they have been the victim of some misfortune - a front jackman getting hit in the groin, for example.

While mechanics may remain largely anonymous to the wider public, drivers - on the whole - are quick to praise their team after a victory, with world champion Lewis Hamilton a prime example.

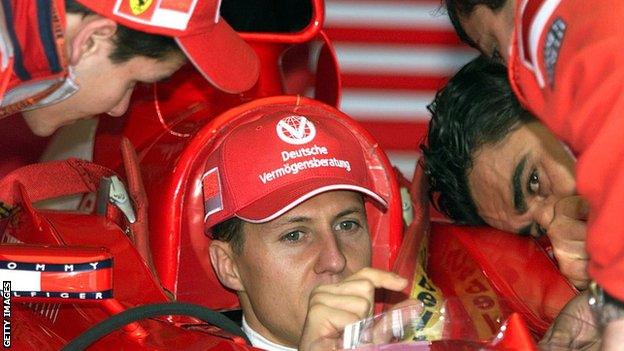

Sebastian Vettel has a British sense of humour and always found time to speak to his team, says Handkammer

Not everyone is the same, however.

"They are a bit of a mixed bunch to be quite honest," reveals Handkammer.

"You do get some drivers who won't even come and talk to mechanics. These mechanics work with them 24/7 but these drivers won't communicate with them.

"You have to be selfish and have a bit of an ego to be successful, but for some to not even communicate is a shame.

"I am lucky that I worked with some fantastic people, though.

"Michael Schumacher and Sebastian Vettel would come to talk about their private lives and they would also show an interest in you - ask about your family.

"Nelson Piquet was great for practical jokes. He was always trying to wind up Alessandro Nannini, while Jean Alesi was also a fantastic guy. At the end of one year he flew a whole crew out to Avignon and put them up, organising events like karting and stuff, and that was two weeks before his wife was due to give birth."

Michael Schumacher had an excellent working relationship with his mechanics but, according to Handkammer, the same could not be said about every driver

So why do it?

Given the hardships, some may wonder why on earth anyone would become a mechanic in F1, but it can be incredibly rewarding.

Watching a driver win, or just complete a race without any mechanical problems can bring a great sense of pride. However, for a mechanic, there is nothing quite like being part of the perfect pit stop.

"We were in the Guinness Book of Records with the first sub-two-second pit stop," says Handkammer.

"When two cars come in and you beat the other out of the pit stop then that is a real proud moment for the team.

"It almost feels as satisfying as a win. In fact we have won races for the drivers, when they were not going to get past a rival on the track.

"It is a pretty stressful career, but when it all comes together it is unbelievable."

Handkammer's advice for prospective mechanics? Buy a good pair of trainers. It's a long day on your feet

A risky business. Fire broke out at the back of the Williams team garage after they celebrated winning the 2012 Spanish Grand Prix

- Published1 October 2016

- Published26 September 2016

- Published30 September 2016

- Published1 October 2016

- Published29 September 2016