Bernie Ecclestone: Why F1's titanic leader was loved and loathed

- Published

Ecclestone won two world titles with Brabham

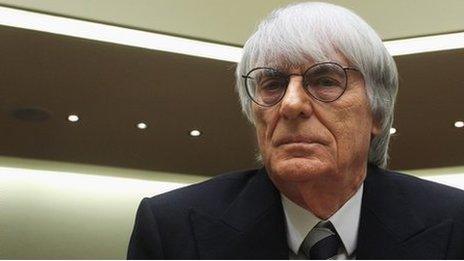

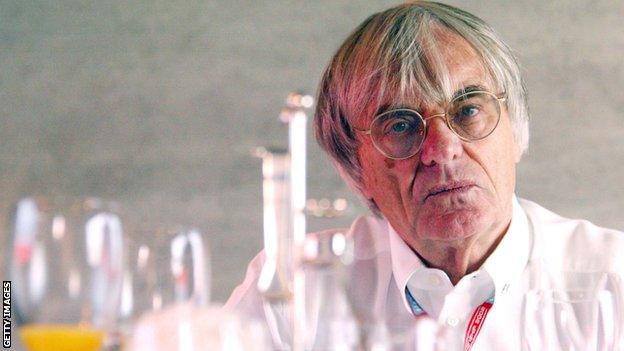

Bernie Ecclestone stands a little under 5ft 3in tall but for 40 years has wielded a giant influence in Formula 1 with canniness, wit and not a little menace.

At times, Ecclestone has had close to absolute power. So the end of his reign following the takeover of the sport by US giant Liberty Media represents a seismic change.

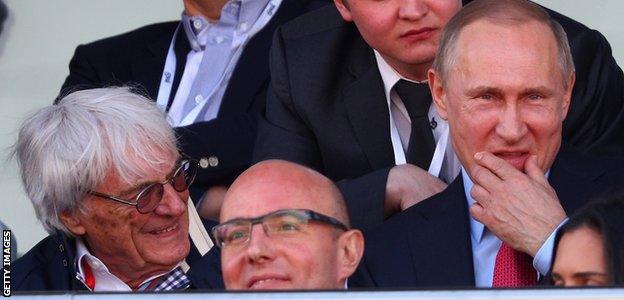

Ecclestone, now 86, is a tactician of remarkable skill, and a deal-maker extraordinaire who used chutzpah and brinksmanship to turn F1 into one of the world's biggest sports, form relationships with world leaders such as Russian president Vladimir Putin and make himself and many of F1's participants multi-millionaires.

In a remarkable four decades, Ecclestone revolutionised the sport:

He bought the Brabham team and won two world titles, including a historic first with a turbo engine in 1983.

Turned F1 into the biggest annual sporting event in the world, outstripped only by the Olympics and the World Cup.

Controversially took the commercial rights away from the teams and made himself a billionaire.

Fought off a criminal prosecution for blackmail that arose from a complicated series of sales of those rights.

Carved a notorious reputation for making controversial statements, including saying Adolf Hitler was "able to get things done" and likening women to "domestic appliances".

But what made him mind-bendingly - some would say obscenely - rich is what brought him down in the end.

Selling on the commercial rights to F1 is the source of Ecclestone's vast wealth. But it was never about the money, per se - it was about the deal. And now the deal has done him in.

Restructuring the finances of the sport in the first years of this decade, Ecclestone also reorganised its decision-making process.

Ecclestone still has a lot to offer - Horner

He did it to increase his power, but the structure he set up inadvertently neutered him and gave the big teams - particularly Mercedes and Ferrari - power to block him. This has led to log-jam.

The latest company to buy the sport - USA's Liberty Media - has looked at this, at a skewed prize-money structure, at a policy that is threatening to price out much-loved historic races in favour of characterless new ones in countries with questionable regimes, at a refusal to engage with digital media, and several other issues, and decided to ease him out.

Ecclestone is held in genuinely high regard within F1 for everything he has achieved but, outside a handful of acolytes, few will be genuinely sorry to see him go.

There has been a feeling for some years that he is a man out of time, that the sport needed to move on. In truth, this has contributed to the stalemate in F1 - people were simply waiting him out.

Many believe his departure will be good for the sport. However, it will certainly make F1 less colourful, and it is hard to imagine seeing the like of him again.

Where did he come from?

Ecclestone's involvement in F1 started in the late 1950s. After a brief driving career in lower categories, he emerged as a manager for the British F1 driver Stuart Lewis-Evans but then disappeared from racing when Lewis-Evans was killed in a fiery crash at the 1958 Moroccan Grand Prix.

He appeared again in the late 1960s, again as a manager, this time to the Austrian Jochen Rindt. He was already very rich.

Ecclestone (second from right) with James Hunt, Niki Lauda and Ronnie Peterson before the 1976 Japanese Grand Prix

What had the fortune come from? "Property," Ecclestone says. All manner of rumours have abounded, including that he was involved in organising the Great Train Robbery, when £2.6m was stolen from a Royal Mail train in Buckinghamshire in 1963.

"Nah," Ecclestone once said. "There wasn't enough money on that train. I could have done something better than that."

Rindt became F1's first and so far only posthumous world champion after he was killed at the 1970 Italian Grand Prix. But this time Ecclestone did not retreat.

Within a couple of years, he bought Brabham from its founder, the three-time world champion Sir Jack Brabham, and began establishing his power base.

How did he become omnipotent?

Back then, circuit deals and television rights were operated on a somewhat haphazard, piecemeal basis. Ecclestone offered to look after them on the teams' behalf and wasted little time in building his influence.

He persuaded television companies to buy F1 as a package, rather than pay for individual races. That guaranteed vastly increased exposure, and the sport's popularity grew increasingly quickly.

The F1 supremo's willingness to deal with controversial global leaders, such as Russian president Vladimir Putin, often raised eyebrows

The vast growth of F1 from what it was then to what it is today arguably started in earnest after the 1976 season, when a championship battle between the playboy Englishman James Hunt and the ascetic Austrian Niki Lauda caught the public's imagination.

By the 1980s, F1 was becoming a global sport, more and more races were being shown live, and a generation of charismatic stars enhanced its appeal - Alain Prost, Nigel Mansell, Nelson Piquet and, most of all, Ayrton Senna.

Ironically, Senna's death in 1994 only increased its reach and shortly after that the sport started on the route that has led to Ecclestone's departure.

The beginning of the end

Controversially, in the mid-1990s, Ecclestone struck a deal with his long-time friend and ally Max Mosley, who was then the president of governing body the FIA. It saw his own company become the rights holder of F1, taking over from the teams' collective body that Ecclestone previously ran.

This led to a furious row with some of the teams - particularly McLaren, Williams and Tyrrell - who claimed what Ecclestone was doing was illegal and that he was effectively robbing them.

But the complainants were eventually bought off. Ecclestone then set about monetising his new asset.

Ecclestone acquired the commercial rights to F1 in 2000, when close ally Max Mosley was in charge of the FIA

In 2000, Mosley granted Ecclestone the commercial rights to F1 until the end of 2110 for a one-off fee of $360m. Even then, many were shocked by the relatively paltry amount of money that changed hands to secure such a lucrative and lengthy deal.

This led to a dizzying series of sales as the rights transferred through various institutions. A German cable TV company bought them, and then collapsed, which led to its creditors - banks - taking its assets. In 2006, the German bank BayernLB sold its 47.2% stake in F1 to an investment company called CVC Capital Partners.

CVC ran the sport for 10 years, employing Ecclestone as chief executive and empowering him to carry on as before, before selling to Liberty last September, in the deal completed on Monday.

But the sale from BayernLB to CVC is what ultimately led to the court cases on bribery charges that Ecclestone fought and survived a couple of years ago - and which he ended by paying the German courts $100m to end the case, without a presumption of guilt or innocence.

It did not escape notice that a man charged with bribery had paid - perfectly legally under German law - to end a criminal trial.

What is he like?

Despite his diminutive stature, Ecclestone is a forbidding character. Stories abound in F1 of real and threatened menace.

A conversation with him is akin to juggling sand - he ducks and dodges and avoids questions with obfuscation, distraction and quick wit, a dizzying mix of truths, half-truths and fallacies.

He is approachable but apart, engaging but unknowable. After a verbal sparring match, he will sometimes reach up and chillingly pat you on the cheek, not unlike a mafia don in the movies.

With David Coulthard, Michael Schumacher, Mika Hakkinen and Rubens Barrichello in Hungary, 2000

For years, the more unsavoury aspects of Ecclestone's stewardship were glossed over or laughed off - largely because he was making those he was working for so much money.

But in recent years, the tone in F1 has changed as more and more people began to feel he was past his sell-by date.

He was a reluctant embracer of the internet age, and rejected entreaties to try to use it to extend F1's reach.

His argument was that he saw no way to make money out of it; others argued that his modus operandi of pursuing only the deal, the bottom line, and disregarding its potential longer-term effects was doing more harm than good.

His simple model - sell television rights and races to the highest bidder no matter who it was; squeeze the highest price possible out of continuing partners - created an annual global revenue in the region of $1.5bn (£1.2bn).

Yet he became increasingly haphazard and intransigent in his decision-making, coming up with unpopular ideas such as a double-points finale in 2014 or the fiasco over the change to the qualifying format at the start of 2016 - to try to spice up the sport.

He was responding to declining audiences, but seemed to ignore the fact they were dropping largely because of his switch away from free-to-air towards pay television in key markets, and the questionable effect on the racing of gimmicks such as the DRS overtaking aid and tyres on which drivers could not push flat out.

The declining audiences have led to a crisis of confidence within the sport, the response to which is a new set of rules for 2017 that mean faster, more dramatic-looking cars. But already there are concerns that these may not have the desired effect.

An incredible legacy

But while the problems are real, the fact remains that F1 has just changed hands in a deal that values it at $8bn (£6.4bn).

And that is almost entirely down to Ecclestone and what he has built with his remarkable personality, vision and drive.

Controversial he certainly was; past his best he may have been. But for all his faults, Bernie Ecclestone is a unique and titanic figure who turned what was essentially a niche activity into a glittering global enterprise that to many represents an intoxicating mix of glamour, danger and raw, unmatched drama.

Gone from power he may be, but he will never be forgotten.

- Published23 January 2017

- Published18 January 2017

- Published16 September 2016

- Attribution

- Published8 September 2016

- Published5 August 2014