Malaysian Grand Prix: What can you do with an old F1 track?

- Published

- comments

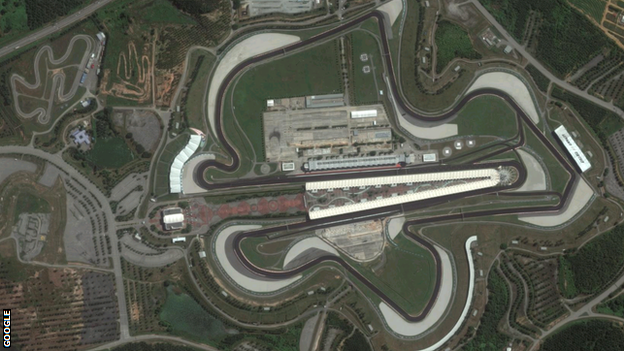

Sepang led the expansion of F1 out of its heartlands and into new territories

The 2017 Malaysian Grand Prix will be the last at the Sepang circuit - at least for the time being - because of financial issues.

Sepang joins many evocative names from the past - Kyalami, Zandvoort, Estoril - as well as perhaps less evocative ones like Buddh and Yeongam, in being a circuit left behind by motorsport's elite.

But what can a track do when F1 moves on?

Embrace the motorsports

The drama in Jarama is all now somewhat calmer

Spain's Jarama circuit near Madrid was deemed too narrow for F1 as far back as the early 1980s.

As a result Spain lost its Grand Prix for five years, until the Circuito de Jerez opened, followed by a new track near Barcelona, where F1 has raced (and tested) ever since.

Jarama, though, continues to thrive - hosting sports car, touring car and motorcycle races - even trucks.

Imola in Italy - the former venue of the San Marino Grand Prix, and once, back in 1980, the actual Italian Grand Prix, while Monza was being redeveloped - does much the same, with the 6 Hours Of Imola sports car race a highlight of their calendar.

Imola has, meanwhile, been battling Monza in the courts to get the Italian Grand Prix back - a fight it only finally gave up last year.

Try a different sport

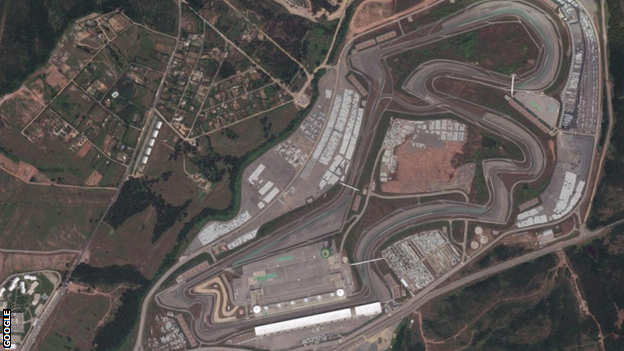

Rio's new Olympic Park sits on top of the old Jacarepagua track

Here are some things racetracks tend to have in common: they take up a lot of space; they have good transport links; they are temples for sport fans; everyone knows where they are.

The British Grand Prix used to be at Aintree, after all.

With that in mind, if the circuit isn't doing much, why not try putting a different sport in there?

That is what Rio did when it won the right to host the Olympics for 2016.

Brazil used to rotate its Grands Prix between the old, long Interlagos circuit in Sao Paulo and Rio's Jacarepagua - later named the Autodromo Internacional Nelson Piquet in honour of the triple world champion.

But after Interlagos was redeveloped - and as Rio's Piquet became thoroughly eclipsed in the affections of the Brazilian public by the Paulista Ayrton Senna - Jacarepagua and its stunning backdrop was abandoned.

So when Olympic planners needed a big space to put the Olympic Park, it was exactly what they needed.

Push for a comeback

Istanbul's Turn 8 is the most famous corner of F1's "new" tracks

Historically, tracks tended to drop off the calendar as they were deemed too unsafe as the sport got faster - Oporto, Montjuic Park, Rouen-Les-Essarts. Now it tends to happen because the costs have become too much. Sort that out, and you could have a Grand Prix again.

Istanbul Park - once described by Bernie Ecclestone as "the best race track in the world" - has been off the schedule since 2011, but its owners are optimistic that can be reversed.

Istanbul Park's owner Vural Ak told reporters earlier this year that he had "agreed in principle" a deal to get back on the 2018 calendar. Although that has not happened, Turkey is probably the most likely track to make it back to F1.

The owners of India's track at the Buddh International Circuit also sound hopeful, if less confident, that F1 will return "when the situation improves."

Redevelop and bounce back

The shape of the old Mexico City circuit is clearly visible within the new one

Austria's A1 Ring and Germany's Nurburgring are two tracks now on the F1 calendar that are completely different to the ones originally built, after those were deemed unsafe.

South Africa's Kyalami did the same and for the same reasons, although that only lasted two races in 1992 and 1993.

Most recently, Mexico City - off the calendar since 1992 - reappeared, with most corners changed, although still the same basic outline as before.

Argentina's track at Autodromo Oscar Alfredo Galvez in Buenos Aires keeps attempting the same thing, but it hasn't quite happened yet - Ecclestone once saying "we are open to racing in Argentina when I can deal with serious people."

Argentine greats of the past have included the legendary Juan Manuel Fangio, but with a struggling economy and without a big star in the modern era, it is an uphill struggle.

Hope for a local hero

Zandvoort has hugely changed since its F1 days - but its famous first Tarzan corner is still intact

There is nothing like having a successful driver (or team) from your country to drive fans to a Grand Prix.

The love for Ferrari in Italy meant the country had two races from 1981 to 2006.

The success of Michael Schumacher resulted in Germany's Nurburgring being used in addition to Hockenheim, and later, Spain's love for Fernando Alonso secured a second race there, a street circuit in Valencia.

So with Max Verstappen a massive hero in the Netherlands - and with so many of his fans flocking over the border this year to watch him in Belgium - could the Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort make a comeback?

Located by the seaside, Zandvoort was always one of F1's most popular tracks, but it lacked safety features, and the lack of a big Dutch name in the sport meant it was vulnerable when F1 began to look outside of Europe.

If Verstappen becomes the megastar he threatens to be, perhaps F1 will hit the beach once more.

Use it as inspiration

Yeongam's isolation is obvious from the air - in swamps miles from anywhere

South Korea's circuit at Yeongam is most memorable for massively denting Mark Webber's title charge in 2010 - almost certainly, a decent finish and that year's crown would have gone to him and not team-mate Vettel.

Even before a car had turned up it was in trouble - the facilities were not finished and the safety check had to be delayed.

Ultimately the Korean Grand Prix lasted only four years. The problem was that it was too far away from anywhere. The numbers that came were nothing like enough to cover the costs.

But the handful of races staged in Yeongam are credited with inspiring a new interest in F1 among South Koreans, and ignited a quest to be the country's first F1 driver.

To this end, South Korea has since built a number of smaller racetracks near Seoul and other major population centres.

But unlike Buddh or Istanbul, no-one seems to be pushing very hard for F1 to come back.

Abandon it altogether

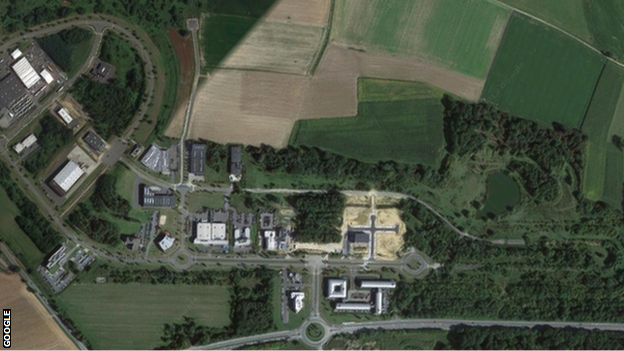

The outline of Nivelles is still basically visible from the sky

Nivelles in Belgium is a classic example of how not to do it.

It was built in competition with the magnificent Spa-Francochamps, at a time when Belgium would alternate its Grands Prix between Flemish and Walloon areas.

It was designed to be safe, in comparison with Spa - but its massive run-off areas meant the crowds were too far back, meaning numbers dwindled and it was bankrupt within three years of opening.

The last race there was in 1974 and it lost its circuit licence altogether in 1981. Since then, it has simply been left, with nature slowly taking back what was there.

- Published26 September 2017

- Published7 April 2017

- Published11 April 2017

- Published21 November 2018