Helle Nice: The incredible life story of the first Women's Grand Prix winner

- Published

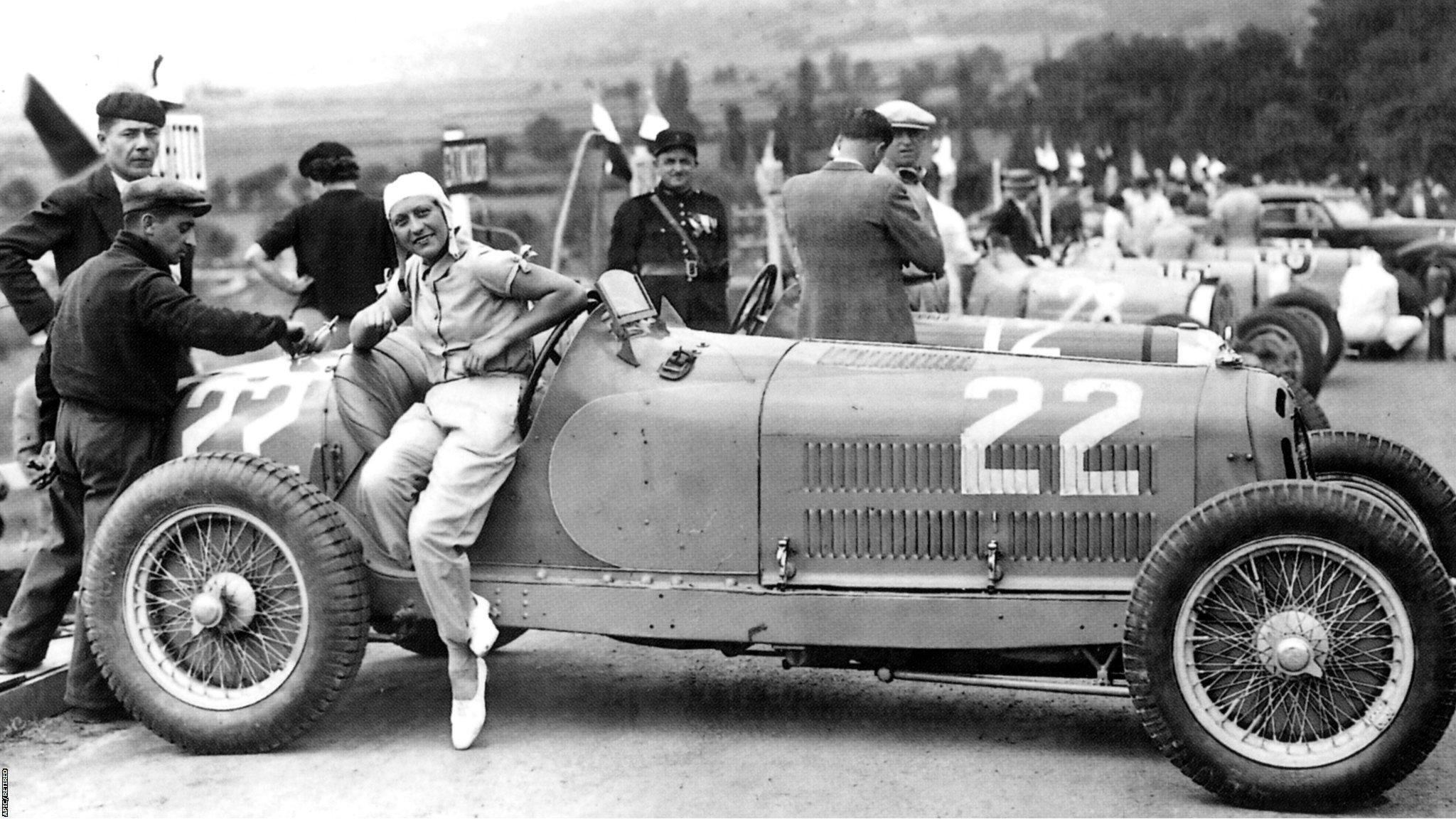

Helle Nice was known as the Bugatti Queen

A new motor racing series aimed exclusively at women is to launch in 2019, with the aim of finding the world's first female Formula One champion.

Motorsport remains largely dominated by men, a detail the inaugural W Series hopes to change. But high-level women's racing has, over the years, produced some extraordinary talent - and the almost-forgotten life story of Helle Nice, winner of the first ever Grand Prix for Women in 1929, is among the most extraordinary of any driver in motor racing history.

"It's all I ever ask for, just to show what I can do without a handicap against men," said Nice in 1930. At the time she was one of the most famous women in the world.

Even now, nearly 90 years later, it seems remarkable that she achieved such prominence in her profession - because today it is one in which women barely feature.

Nice took on and beat the great racing drivers of her day, broke the world land speed record, had affairs with Europe's richest men and appeared on the front page of magazines across the world.

Yet when she died alone in a small house in Nice in 1984 - after years of being so poor she stole milk left out by neighbours for their cats - her name was left off the family gravestone and until recently, seemed lost in history.

From centre stage to driving seat

The 1903 Paris to Madrid motor race passed through the young Helle Nice's village

Nice's real name was Helene Delangle. She was born in 1900 in Aunay-sous-Auneau, a tiny village 47 miles from Paris.

When she was three, the epic Paris to Madrid motor race passed through her village. Its status as the most important event of the day was underlined by the entrants - including Charles Rolls of Rolls-Royce, Vincenzo Lancia, founder of Lancia, and the brothers who founded Renault, Marcel and Louis.

Whether the memory of 224 mechanical beasts thundering through the village is what inspired her love of racing cars is unknown. She had two other careers before her driving seriously took off.

She moved to Paris as a teenager and soon settled into life as a nude model, posing for artist Rene Carrere who was famed for titillating drawings used to advertise music hall shows.

Encouraged by Carrere to take ballet lessons, his muse moved from appearing in the adverts to the shows themselves. Performing came naturally to her, and it lead to her adopting the stage name, Helle Nice.

She was immediately popular and earned enough to buy her first car, a Citroen.

Nice's best friend was racing driver Henri de Courcelles, who introduced her to the great motor circuits just as Grand Prix motor racing was beginning to bloom across Europe.

In 1921 she went to Brooklands in Surrey, England, and sought to enter a race. But when her application was rejected because she was a woman, she was infuriated.

Her fury maintained throughout the 1920s. She raced when she could but was never allowed to compete properly. Instead, she took to skiing to fulfil her desire for fast thrills.

Meanwhile, her dancing celebrity continued to grow, reaching its peak when she performed in a show titled Les Ailes de Paris (Wins Over Paris) in 1927.

But in 1929 her showgirl career came to an abrupt halt. While skiing, she heard an avalanche behind her and leaped a vast gap to escape it. Had she not made it she would have been killed, but the landing damaged her knee badly.

No longer able to dance nor ski, but fired by a desire to continue to push the limits of speed, Nice decided to commit to a life as a racing driver.

First win

Nice set record after record at the purpose-built Montlhery Circuit

That year, the first ever Women's Grand Prix was staged as part of the third Journee Feminine de l'Automobile - a weekend of female-only races - at Montlhery, France's first purpose-built racetrack.

Nice was determined to win, driving 10 laps of the circuit twice a day in preparation. But before the race on 2 June 1929, she indulged in a long night of champagne, morphine and sex.

She won regardless, driving an Omega Six given to her to car by manufacturer Jules Daubecq, who had been persuaded that pictures of a glamorous female champion in one of his vehicles would help shift stock.

"The driving was magnificent: nobody who saw it would feel able to argue that women drive less well than men," wrote the newspaper L'Intransigeant.

The next day, Nice received a message from the Bugatti company asking her to be their driver.

She accepted and immediately rewarded them, winning the Actors Championship in their car - a major tournament of the day and one in which men competed too.

Nice also secured a contract to advertise the 'cigarette of the championship winner', Lucky Strike, and thousands of posters appeared featuring her face. Within just a few months, she became one of the most famous people in France.

The Bugatti Queen

Nice often outshone her male competitors, many of whom she had a great rapport with, but didn't manage to cross the finish line first

The next couple of years saw her fame extend worldwide.

She returned to Montlhery, this time in a Bugatti, in December 1929 to set a new land speed record for women of 197.7km/h.

In 1930 she went to the US to race on dirt tracks in supercharged Miller cars. Initially she was signed as a salaried exhibition driver, taking the wheel without any helmet "because the crowds always like to see my hair when I am driving."

She signed another massive advertising deal, this time with Esso, and became known as the Bugatti Queen.

Wealthy and now globally famous, she returned to Europe in 1931 with the determination to be taken seriously as a Grand Prix racer.

And seriously she was taken. In the first Grand Prix of the season she finished fourth in a race at Reims that featured top drivers Philippe Etancelin, Rene Dreyfus and Louis Chiron.

She raced across France and Italy, receiving the equivalent of what would now be $100,000 as an entry fee for each race she attended.

She won the Women's Grand Prix title time and again.

In men's races, her Bugatti 35C never crossed the line in first place. But Nice was still the centre of attention, often stealing the limelight from the actual winners. And she was rarely less than competitive.

Disaster in Sao Paulo

The Bugatti Queen moved on to driving for Alfa Romeo

In 1933, Nice stopped driving for Bugatti and moved to Alfa Romeo. She finished third in one heat when competing in that year's Monza Grand Prix, though it was a day marked with tragedy as three drivers were killed in a crash. The day is remembered in motor racing as Black Sunday.

Then in 1936, she experienced her own run with death while racing at the Sao Paulo Grand Prix in Brazil, a country in which she was hugely popular.

She was in third place on the final lap, and as she came up behind Manuel de Teffe in second, she swerved and her car went into the crowd, killing six people.

Nice was in a coma for three days, but survived - though photographs taken after the crash show her laid out as if one of the dead.

The severe head injuries she had sustained, coupled with damage to her reputation, left her unable to find a manufacturer willing to take her on.

In an attempt to prove herself, she signed up to the Yacco endurance trials for female drivers at Montlhery. With a team of four other women, she drove for a straight 10 days and 10 nights, breaking 10 records that still stand today.

But still the sponsors stayed away.

Then came the war.

Death in poverty

Photographs of Nice unconscious appeared on the front page of Brazil's newspapers following the fateful Sao Paulo Grand Prix crash

How Helle Nice got through World War Two without suffering too much interference from the Nazis while they occupied France remains a subject of intense debate.

What seems certain is the allegations that she had been a Gestapo spy, made against her by Chiron on the eve of her planned comeback at the 1949 Monte Carlo rally, were untrue.

But despite being false, Chiron's claim was deemed true by both Nice's potential sponsors and her family, with whom she had long been distant.

Her career was effectively over.

The final 35 years of her life were a slow decline, made worse when her lover left her for a younger woman in 1960.

Penniless, she came to rely on donations from an actors' charity - the same sort of organisation she helped to raise money for during her time as a showgirl.

At the age of 75, she was forced to move into an attic in a run-down part of Nice, where she later died, aged 83.

Neighbours told her biographer, Miranda Seymour, they remembered seeing Nice "taking the milk out of the cats' saucers because she had nothing to eat or drink."

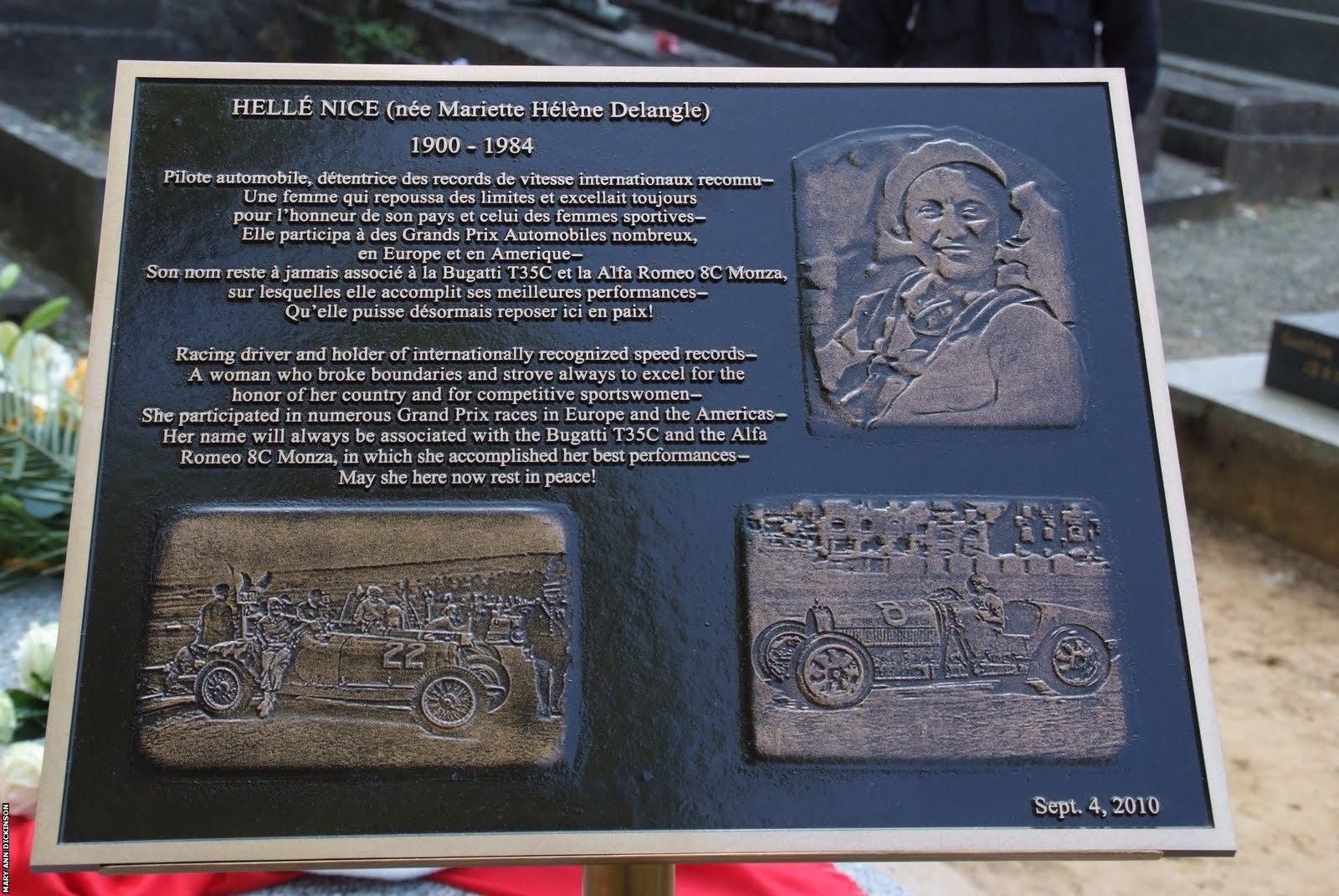

Nice's family, from whom she had long been estranged, refused to add her name to their memorial stone, and it took Seymour four attempts to find the unmarked grave. But a foundation set up in her name 24 years later did put a memorial plaque beside her grave, which is working to restore Nice's reputation as one of the world's greatest female racing drivers.

A name lives on

In 2010, The Helle Nice Foundation erected a plaque by the racing driver's unmarked grave, celebrating her achievements

When the names of motorsport greats are listed - from Juan Manuel Fangio to Lewis Hamilton - they have one thing in common: they are all male.

In the 1960s and 70s, one or two women did compete in the Formula One World Championship. Italian Lella Lombardi got the only (half) point achieved by a woman in the 1975 Spanish Grand Prix. Others competed in F1 cars in non-championship events - one such race being won by South African Desire Wilson, which resulted in a grandstand at Brands Hatch being named after her. And today in the US, Danica Patrick is a renowned top level driver.

But far more famous than all of them, in her time, was Helle Nice.

Much of the detail of Helle Nice's life was established by Miranda Seymour in the book The Bugatti Queen.

- Published10 October 2018