What's the future for F1 engines and why is it up for debate?

F1 cars, such as Lewis Hamilton's Ferrari, use 1.6-litre V6 turbo hybrid engines

- Published

Christian Horner's phone rang. It was Bernie Ecclestone. Red Bull's team principal picked up, switched to speakerphone and placed it on the table in front of the assembled Formula 1 bosses.

We're in the F1 Commission, Horner told Ecclestone. Is there anything you want to say to the room?

F1's former impresario, addressing the group that decides the sport's rules, said they should go back to V10 engines. Then he hung up.

That phone call - described to BBC Sport by several sources in the room at the time - took place in the morning of the day of F1's season launch at the O2 Arena in London in February, where both Horner and governing body the FIA were booed by the 15,000-strong crowd.

Two days later, FIA president Mohammed Ben Sulayem - a man whose three-year tenure has been beset by controversy - posted a message on Instagram.

Ben Sulayem said he "looked forward" to the new chassis and engine rules that are to be introduced in 2026, but that the FIA "must also lead the way on future technological motorsport trends.

"We should consider a range of directions, including the roaring sound of the V10 running on sustainable fuel."

These developments have kick-started a debate inside F1 about engines. The ground is shifting fast, so what's going on?

What are the 2026 engine rules?

Next year, F1 is going through the biggest regulation change in the sport's history, introducing new rules for both cars and engines.

On engines, F1 is sticking with 1.6-litre V6 turbo hybrids, the basic architecture that has been in place since 2014, but changing the balance between electric and combustion power.

The amount of total power provided by the hybrid is going up to about 50% from about 20% now. In addition, F1 is introducing sustainable fuels - abandoning fossil fuels in favour of synthetic fuel created from biomass and industrial processes.

This is all part of the sport's pledge to become net-zero carbon by 2030.

So where has the V10 chat come from?

F1 in 10 Years: Lando Norris

Ever since hybrid engines were introduced in 2014, some have bemoaned the loss of the louder, more dramatic sound produced by the naturally aspirated engines that preceded them - especially the 3.0-litre V10s last raced in F1 in 2005.

In an unavoidable parallel with Ben Sulayem's actions now, Ecclestone was the first person to bring this up, even before the 2014 engines first raced.

A certain romanticism about the V10 sound has sustained, as has the idea that those engines - with their ear-splitting shriek that could be heard some distance from the track - are more popular with the fanbase than the current hybrids.

Within F1, there is no question that some people agree. Lewis Hamilton said at the Chinese Grand Prix last weekend: "It is no secret that the V6 has never sounded great.

"I remember the first time I came to an F1 race in 1996 in Spa and arriving and Michael (Schumacher) coming through Turn One and my rib cage just vibrated. I was so hooked. It was the most amazing thing I felt and heard.

"Over the years we've lost that. If we are able to move back to those amazing sounding engines and still able to see the sustainable goals, why not?"

Fernando Alonso took his 2005 title-winning Renault R25 - with V10 engine - for a demonstration run on track before the 2020 Abu Dhabi Grand Prix

Why has this come up now?

It's not that long since Ben Sulayem was trumpeting his involvement in the introduction of the 2026 engine rules.

These were fundamentally settled under the previous FIA president Jean Todt, but there was inevitable wrangling and it got over the line only after Ben Sulayem took office.

Two years ago, he said the new engines were "at the forefront of technological innovation, making the future of F1 more sustainable while maintaining the spectacular racing".

So why the U-turn?

Ben Sulayem has asked his F1 single-seater director Nikolas Tombazis to look into the matter.

Tombazis said that the advent of sustainable fuels could allow F1 to make the engines simpler and cheaper.

"That's why the president made the comments about V10 engines in '28 - or '29 or whatever - and so on," Tombazis said. "And that is something we are evaluating with the manufacturers."

What's the counter-argument?

Senior figures within F1 and the car manufacturers involved in the sport see many problems with the FIA's position.

On a macro level, the climate crisis is very real, and the global road-car industry is heading in the direction of electrification - even if Donald Trump's election at the head of a government of climate deniers has given pause for thought in the US.

Manufacturers take part in F1 fundamentally for marketing reasons, and the sport has been made more appealing by the introduction of a budget cap for cars and engines.

Audi, Ford and General Motors are all entering F1 in 2026 - and Honda are staying rather than withdrawing - specifically because of the new engine rules.

Audi has already released a statement in response to the latest developments, saying that the new rules "were a key factor in Audi's decision to enter Formula 1".

Mercedes says it is open to discussions but would need a hybrid element to be part of any new engine formula for it to remain interested.

Then there is the micro level.

Why a V10? No major road-car manufacturer uses them any more.

Mercedes says a V8 would make more sense if a change was to be made, as at least they are still being developed for road use.

And why abandon turbochargers, when many performance road cars - from Audi RS6s or Mercedes AMG C63s to McLaren and Ferrari hypercars - use them for very good reasons?

Cost? Yes, a V10 might be cheaper than a hybrid. But the manufacturers have already spent an estimated collective $400m on the new engines. They are not about to throw that away.

And a new V10 would require developing, to the tune of hundreds of millions more.

Weight? Yes, the hybrid engines make the cars heavier, largely because of the batteries needed. But the majority of the weight increase from 550kg or so in 2005 to about 800kg now is accounted for by advances in safety, such as the halo head-protection device.

On top of that, in 2013, cars started races with about 160kg of fuel. Now, it's about 100kg and it's expected to be about the same next year. Returning to naturally aspirated engines would mean a huge increase in fuel capacity - and weight.

Sustainability? The new fuels being introduced next year are not net-zero carbon. According to scientific standards, sustainable fuels reduce carbon emissions by a little above 80%.

That's a lot. But doubling the amount of fuel used by abandoning hybrid engines would mean a doubling of the carbon emissions produced by fuel.

The emissions from the cars themselves are minuscule in the big picture - F1's transport around the world is much more significant. Still, the symbolism matters.

Is there a political angle?

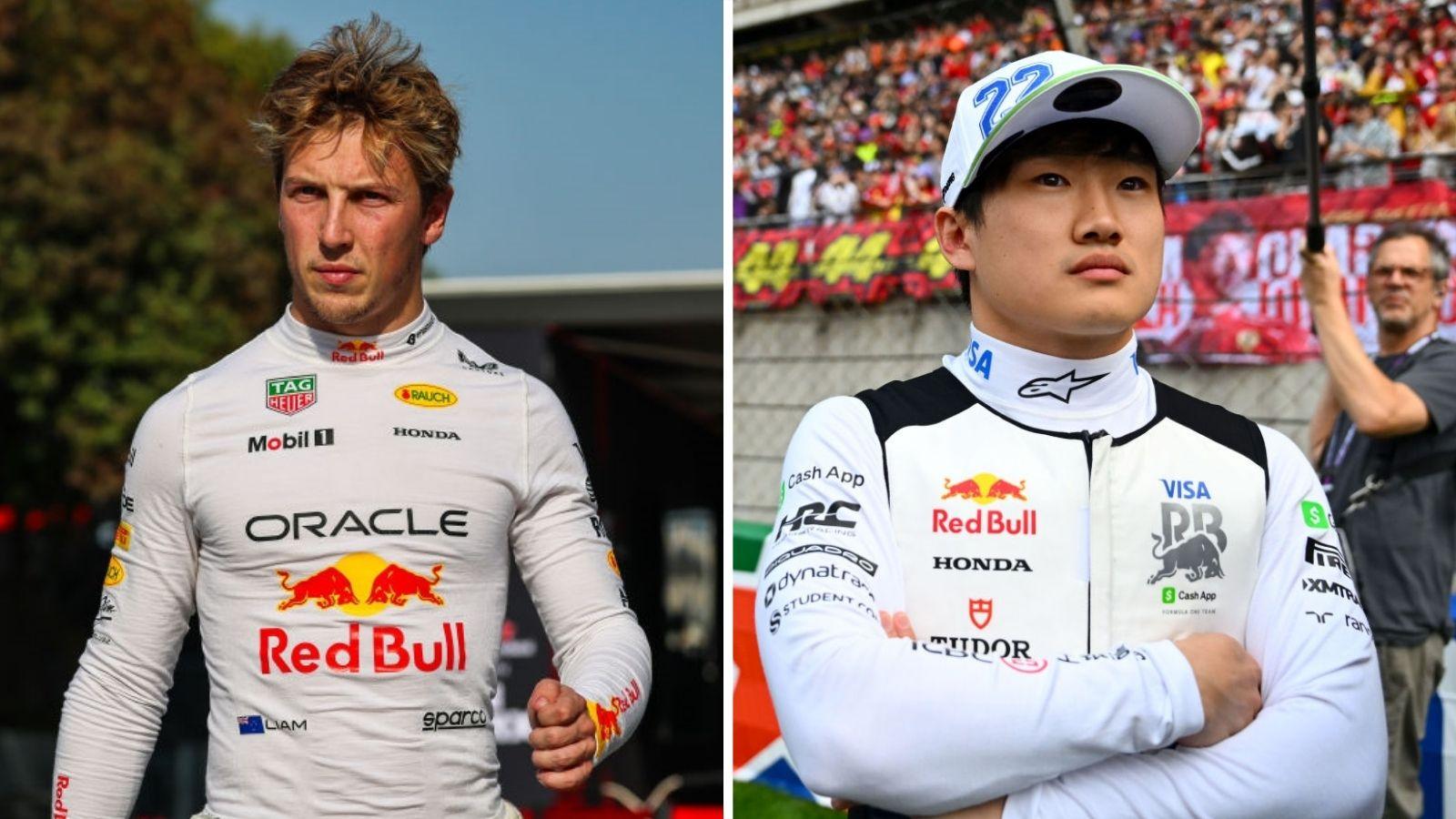

Red Bull boss Christian Horner and FIA president Mohammed Ben Sulayem are both said to be interested in a return to V10 engines

In F1, politics are always involved.

It has escaped the attention of few that Ben Sulayem's intervention came after the crowd at the O2 booed when the FIA logo was shown.

This is an election year at the FIA, and some believe Ben Sulayem may have raised the idea of V10s because he thinks it will be popular with certain demographics who support him.

So far, no candidate has put themselves forwards to oppose him, but there are whispers that there is a credible opponent in the wings.

At the same time, word is creeping out in F1 about the progress the various manufacturers are making with their 2026 engines. And it seems that Mercedes are leading the way.

People are already beginning to say that a team will only win in 2026 if it has a Mercedes engine.

Of course, there is no proof of this, but the whispers are emerging in exactly the same way as similar ones did in 2013 - and they were proved exactly right when the hybrid engines made their debut the following year.

The V10 proposal is seen by rival teams as very much a Horner-Ben Sulayem agenda, even if it is said to have some support from Ferrari.

Could the 2026 rules be abandoned?

Even Horner, while saying that "the concept of a V10 would be very exciting for the sport" acknowledges that abandoning the rules would be "a massive departure from what is being worked on very hard for 2026".

A U-turn for 2026 now would need support from the teams and manufacturers - and there is not a chance that enough of them would support that to get it through.

A leading team boss told BBC Sport on condition of anonymity that there have been "zero discussions" of this idea in the group of F1 stakeholders.

It takes time - years - to agree engine rules.

It would probably be two years before a full agreement could be reached. Then the manufacturers would need the same time again to develop and build the engines. Which would take F1 to the end of 2029. Which is only a year before the new rules are due to expire anyway.

As one team boss puts it: "I think this will all peter out, and it will just end up becoming: 'What will 2031 look like?'"

The FIA says: "There needs to be a consultation between all stakeholders to agree on a way forward, before we fully explore different scenarios.

"Whichever direction is chosen, we must support the teams and manufacturers in ensuring cost control on R&D expenditure and take account of environmental and sustainability considerations."

And the chances of the end result being a naturally aspirated V10, in the context of all the above? Not high.

Related topics

- Published17 October 2024

- Published7 days ago

- Published25 March

- Published27 March