The GAA Social: 'The hurling field & primary school were 50 yards apart. One was heaven, one was hell'

- Published

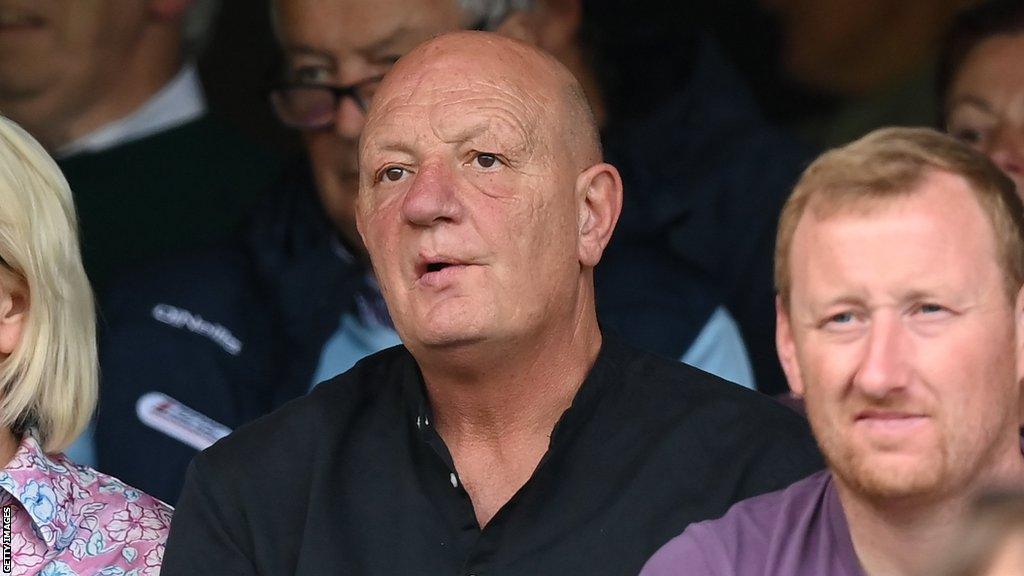

McNaughton believes his traumatic experiences at school helped form the strong mindset he used to his advantage on the hurling field

Terence McNaughton remembers it all so vividly.

He remembers the stammer that crippled his confidence as a child. Some kids talk too much, but so repressed was McNaughton by his speech impediment, something as insignificant as going into the shop to ask for a packet of sweets was beyond him.

He remembers a "horrendous" childhood, one where his best friends were a hurl and a ball.

McNaughton has a great way with words now, though. On The GAA Social, he says that, for him, heaven and hell - the hurling field and the primary school - were 50 yards apart.

A lot of kids in the 1970s had a rough time in school, but McNaughton's sounds particularly harrowing.

He was bullied, abused, neglected.

He recalls: "In P3, the teacher made me sleep at the back of the class. I never got homework.

"In P7, the teacher used to enjoy bringing me up to the front of the class and making me read, hitting me in the back of the head with a book."

The misery inevitably took its toll. By the time McNaughton reached secondary school, he was "unteachable".

He now regrets leaving school without the ability to read and write, but what he lacked in the classroom he made up for on the hurling field.

The hurl and sliotar became his pencil and paper, the pitch his classroom: a student of the small ball.

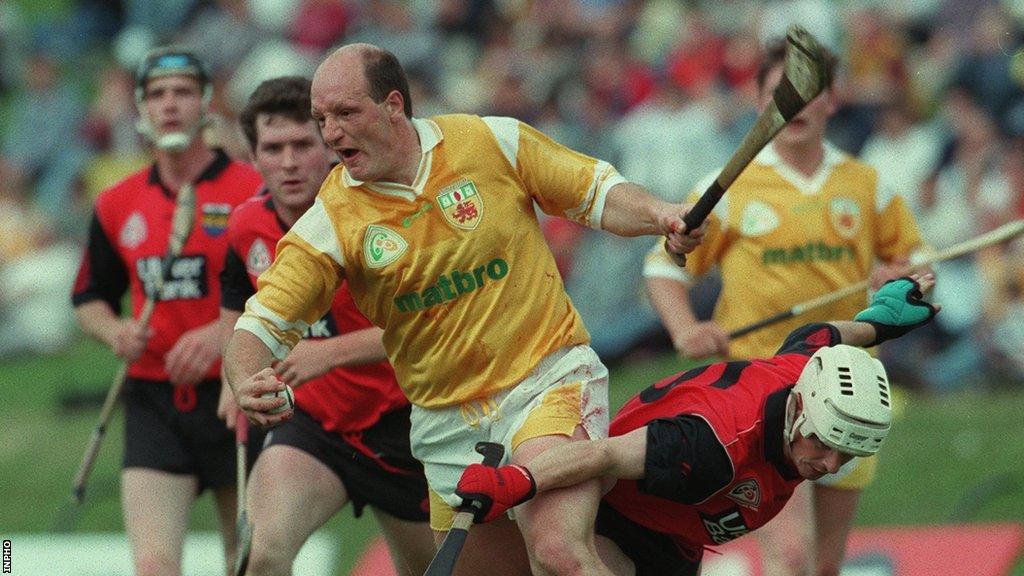

He says hurling "saved" him. Even without the luxury of speaking confidently, McNaughton became a force in the sport. He is now regarded as one of Antrim's greatest-ever players - and one of the greatest players never to win an All-Ireland medal.

An All-Star in 1991, he started the 1989 All-Ireland Hurling Final against Tipperary while, at club level, he won a bucket load of county and Ulster titles with his beloved Ruairi Og Cushendall.

Looking back now, he reckons his bruising childhood experiences equipped him with a useful weapon for hurling: a strong mindset.

"My greatest asset was my mindset," says the former Antrim manager.

"There's no question about it. I was hard to hurl on. For 60 or 70 minutes, I wasn't going anywhere.

"I could fill your house with people that were more skilful or athletic than me. I didn't care how fast or good you were, I was there for 70 minutes.

"You were going to be glad to hear the ref's whistle to get shot of me. That was my greatest asset."

McNaughton, pictured during the 1996 Ulster Hurling Final against Down, won an All-Star in 1991

He goes on: "It's only when you start reading the books, you watch The Last Dance or the All Blacks book. I was doing that in another way.

"The story's the same, from the All Blacks to the Chicago Bulls to Oisin [McConville]'s Crossmaglen team that we followed.

"It all comes down to the same. It's that desire and words that are kind of old-fashioned now: guts, desire, will to win and desire.

"If you don't have that desire. You can go to the gym all you want but if you don't have that foundation of desire and that will, you're going to be found out."

When asked by Thomas Niblock if he would have been as good a hurler without the traumatic experiences of his youth, McNaughton said: "No. I don't know where my life would have ended up.

"I could have been in jail or down a whole different path. I don't say that flippantly to make myself sound good. I needed Cushendall hurling club more than it needed me."

'Football has become unwatchable'

In a wide-ranging interview, McNaughton also waded into the ongoing debate around Gaelic football as a spectacle.

With several of the All-Ireland round-robin games having featured no shortage of possession-based, risk-averse football, several observers feel football's entertainment value has diminished drastically.

McNaughton agrees: "I sat down and watched the first half of Louth and Mayo. I went out the back at half-time and read the papers."

For him, it's become "unwatchable" and was outraged by Roscommon keeping the ball for six minutes in their recent match against Dublin.

It is, he feels, far removed from the "pure entertainment" of Munster hurling, which he calls the small ball's "Rolls Royce".

He's noticed, too, that in the bar he runs in Cushendall, people will have their backs turned to the football when it's on the TV.

"The people that need to solve this are the people who caused it," he continues.

"I think the GAA should send the 32 or 33 managers to the Slieve Russell hotel and don't come out until there's white smoke.

"Leave four forwards up the field or something. The only people who are going to watch football are the die-hards and family members.

"You're not going to get the people in Cushendall tuned in to watch the Oisin McConvilles or Peter Canavans or Tony Scullions, or the McKeevers or the Downeys."

Listen to the full McNaughton GAA Social interview on BBC Sounds