Get Inspired: Why attempt a long distance triathlon?

- Published

When Hannah Nicklin was 28 she vowed to attempt a long distance triathlon (sometimes known as an Ironman) the year she turned 30.

What possessed her to set this challenge of 224km (140.6 miles) of swimming, cycling and running, and what carried her to the finish line?

In her one-woman show Equations for a Moving Body, Nicklin explores what it means both psychologically and physiologically to train for and attempt a feat of endurance.

Nicklin is a swimmer, she tells an audience at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.

During research for the show, a sports psychologist picked up on the nuance on why she didn't simply say she swims.

Dr Sarah Partington told her athletes push themselves because of an awareness that they are telling a story about who they are.

Nicklin admits she wanted a milestone of her own, having discounted traditional life markers such as getting married, learning to drive or owning a home.

Essentially, she was adding to the narrative of her life - the stories about her that help demonstrate who she is.

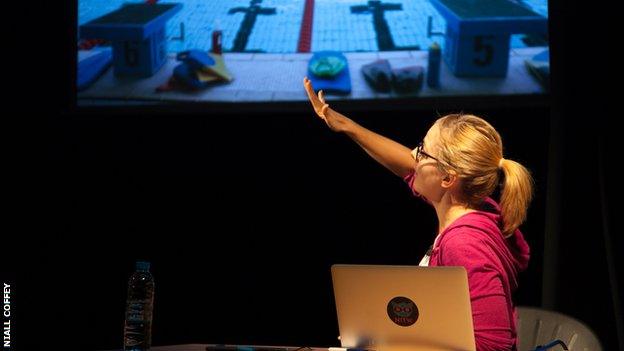

Using a projector screen, Nicklin flicks through tabs on her laptop, from her social media interactions and her personal music library to fitness apps and google maps.

She shows how we use these tools to map our lives and achievements, build friendships and connect to wider communities.

Her triathlon journey twists and turns like some of her training runs around Loughborough, influenced by friends, sports peers, family and her coach.

Nicklin may be a swimmer, but she is also a story-teller. Outside theatre she has sought a variety of methods to present stories, including poetry, video games, and sound-art installations.

Within this performance she has also endeavoured to find the best mechanism to demonstrate each point.

She worked with Alexander Kelly of arts group Third Angel, Simon Ward, a triathlon coach, and interviewed sports scientists and psychologists from the University of Northumbria.

Like a statistician she meticulously explains the physical aspects of what happens to our minds and bodies when we test them in endurance sports.

Numbers clearly matter: her repetitive swimming stroke, her breathing, her stride rate, her timing calculations, and her "maths hour" during painfully long cycle rides.

She describes the beating a triathlete's body takes over the course of a day's competition.

As the body strives to send energy to the muscles, the brain also becomes tired, which can cause negative thoughts.

Describing her fear that she might find the limits of her body's capability, Nicklin takes the advice of an ultra-endurance friend to turn this into a positive, exciting quest.

As well as these scientific explanations, which would leave most of us asking: "Why would you?", Nicklin is also incredibly open and warm.

She weaves in poignant moments of love, friendship, humour and pain - like her mother and brother's pre and post-race embrace, a fellow competitor's promise of a roly-poly over the finish line, and the smug solace in beating a cycling time set by her ex-boyfriend.

Nicklin returns to numbers to silently illustrate the most emotional part of her journey - the devastating loss of a friend and training partner.

John Lamb, from Edinburgh, died aged 34 after falling 3,600ft in Chamonix in the French Alps while snowboarding. It took 20 seconds to fall. She does the maths.

So why do people push their boundaries, especially when the stakes can be so high?

In part it's about mastering skills that help fuel their identities, and it's also about experiencing what their body can do when it's pushed to the limit.

But Nicklin's most powerful message is that it's also about everyday solidarities that push you gently along the road to do extraordinary things.

So she did the "thing". Now she just needs another life milestone, and presumably it won't be something conventional like learning to drive.

For more more information about triathlons, take a look at the Get Inspired guide.

- Published21 September 2018

- Published11 June 2016

- Published1 August 2016

- Published3 March 2016

- Published7 September 2015