Cricket World Cup: Where are all the black English cricketers?

- Published

- comments

Kent opener Daniel Bell-Drummond has set up his own initiative to encourage black children to play cricket

Ask any cricket fan who grew up in the 1990s to name a handful of standout performances by England players, and the chances are they will recall a match-winning performance by a black cricketer.

Perhaps it would be Devon Malcolm's fiery 'you guys are history' spell against South Africa in 1994? Or Dean Headley's memorable bowling display to win the Boxing Day Test in Melbourne in 1998? Then there's Alex Tudor's 99 not out as a nightwatchman against New Zealand six months later.

Those performances - and others by players such as Mark Butcher, Phil DeFreitas and Chris Lewis - could have been the inspirational catalyst for more black cricketers to make their way into the England team.

That - with the recent exception/eligibility of Barbados-born Jofra Archer - hasn't happened.

In 2007, BBC Sport, external asked: "Where have all of England's black cricketers gone?"

That question remains just as, if not more, relevant today - there are just a handful of black or mixed-race English cricketers active in the 18-team County Championship.

So what can be done to encourage and engage those of Afro-Caribbean descent to play cricket, particularly at grassroots and club level?

Bell-Drummond's 'duty' to give back

Bell-Drummond (right) hands out medals to children taking part in cricket sessions in South London

Kent's Daniel Bell-Drummond was born to Jamaican parents in Lewisham, South London, and fell in love with the sport as a child, when he watched his dad play club cricket.

"There is an issue with the number of young black kids playing cricket," the 24-year-old says frankly.

"When I was growing up, I never really thought of that. I just loved the game. But the statistics don't lie. There has to be something done."

Bell-Drummond - one of the leading black cricketers in the country - impressed for the Lions in recent summers.

And he wants to use his growing profile to give back to his local community and get more children playing cricket.

To that end, he set up the Platform initiative, external in 2017.

Bell-Drummond and his team visit primary schools in North Lewisham and introduce the sport into the curriculum, as well as putting on after-school sessions in Deptford Park.

"We target younger kids because we feel at 13 or 14 they are set in their ways, they're in school with GCSEs coming up, and so cricket would probably be a pointless distraction," he says.

"So we work with year four pupils and teach them the game - no real technique, just the basics and to have fun."

'With black communities it's about participation'

The Platform initiative introduces the basics of cricket to school children in Lewisham

In May 2018, the England and Wales Cricket Board launched a new strategy to engage more people of South Asian origin in playing, supporting and getting involved in cricket.

Bell-Drummond believes the two communities face different challenges.

He feels cricketers from South Asian communities are playing in club leagues but few tend to make the progression to county and professional level, while those with Afro-Caribbean heritage need more encouragement to pick up a bat and ball in the first place.

"With black communities it's more about participation, there are not many I've seen from playing club cricket and I am from South London - that's where the hub is - so if there's not many there then there won't be many up in the country," he says.

That is echoed by Eaton Gordon, head coach at Handsworth Cricket Club - a team in Birmingham set up in the 1980s featuring mainly Afro-Caribbean players.

"We started our youth section in 2005 and that was 50/50 in terms of black and other communities. That has now gone to probably 10% Afro-Caribbean and 90% South Asian," he says.

Gordon was interviewed in the 2007 BBC Sport feature, and says he is not surprised the lack of black cricketers is still an issue.

"I didn't think that much would change," he says.

'I stand out, I don't feel like everyone else' - the case study

Amateur side Handsworth CC in Birmingham buck a trend in the professional game

Kieron Buchanan first played the sport as a small child after his uncle bought him a bat. He now plays for Handsworth CC and Warwickshire County Cricket Club's youth team.

The 16-year-old from Birmingham has high hopes of pursuing a career in cricket, but does sometimes feel "different to the others" during a match.

"I'm the only black person in my team. We will normally play against a team where there are no black players," he says.

"I am going to stand out. It's not weird, I just don't feel like everyone else."

Speaking to BBC Sport, an ECB spokesperson said the governing body was aware of the need to engage with "Afro-Caribbean cricket communities in the UK at all levels of the game".

They added: "This reflects our broader strategic aim to make cricket a game for everyone and be as inclusive and representative of all sections of society as we can be."

Decline of West Indies, cost of cricket, shift in culture

Former England bowler Alex Tudor (left) took 28 wickets for Test wickets but is well known for his match-winning 99 not out as nightwatchman against New Zealand in 1999

Bell-Drummond was influenced by both his Caribbean background and his upbringing in England, perhaps best signified by his two cricketing heroes - West Indies legend Brian Lara and former England opener Marcus Trescothick.

"I have always been a batsman so those are the two I looked up to, but Lara especially," he says.

He adds it is too easy to blame the decline of the West Indies national team for the drop in the number of black cricketers in the United Kingdom, suggesting the reasons are far more complex.

"The West Indies haven't been as strong and that's reflected in the community over here but I do think there are other issues, such as the cost of playing cricket," he said.

Bell-Drummond suggests Afro-Caribbean communities are more interested in football than cricket, due to an increase in the number of African footballers playing in the top leagues around the world, and the lucrative nature of the sport.

It is a view Kieron shares.

"I'm the only one of my black friends who plays cricket - they're all about football," he says.

"It's at the point where their parents don't really want to push them into cricket. They probably watched the football World Cup and all they talk about is that, not cricket."

Bell-Drummond also describes a shift in culture, saying some second and third-generation black children do not have the same affiliation to their West Indian heritage as their parents.

"Their grandparents may be from the Caribbean but these boys and girls are English and their parents are probably English too," he said.

"The make-up for the country has also changed - in London there are probably more black people from African descent than Caribbean descent so I do think there's a wider picture to it."

Former Surrey bowler Tudor says stricter guidelines at cricket grounds have also had a negative impact.

"Back in the day, when the West Indies played at Lord's or Edgbaston, it was like a home game," he said in 2013., external

"There were the drums and hundreds of people would bring in some rum and food. But that's all been banned. And it dampened the spirits of the carnival atmosphere that made attending cricket a joy."

'Strategy needed for black communities'

Rainford-Brent enjoyed a successful England career and was part of the 2009 World Cup-winning squad. She is now a pundit on the Test Match Special commentary team and director of women's cricket at Surrey.

Ebony Rainford-Brent, the first female of Afro-Caribbean heritage to play for England, says the ECB needs to implement a similar strategy for black communities to the one targeting those of South Asian origin.

"Without that kind of approach I think we will drift along," she says.

Rainford-Brent was born in Loughborough Junction in South East London to a Jamaican mum and grew up in what she describes as a "typical Caribbean household".

She first took up cricket after a community coach came into her school and introduced her to the sport. She started to play street cricket, then transitioned into the more conventional form.

But Rainford-Brent says, despite being made to feel welcome, she didn't always feel comfortable being the only black girl in the team.

"I knew I was different. My mum would turn up on the bus with a load of bags. Other kids would turn up in bigger cars, coming from private schools," she says.

"When I opened my packed lunch with Jamaican food, the other kids would stay 'it stinks'. It was kind of a joke and wasn't a bad thing but, because there was such a difference, you stood out."

Rainford-Brent also does not feel that gender is an issue when it comes to attracting Afro-Caribbean children to the game.

"There are different challenges for girls in sport but in terms of black communities it's about supporting and getting them to stay in the sport," she says.

"Encouraging black British participation is important but we should also target the disadvantaged communities, because the challenges are similar - they need financial support, help with transport and buying kits."

Can one black superstar make a difference?

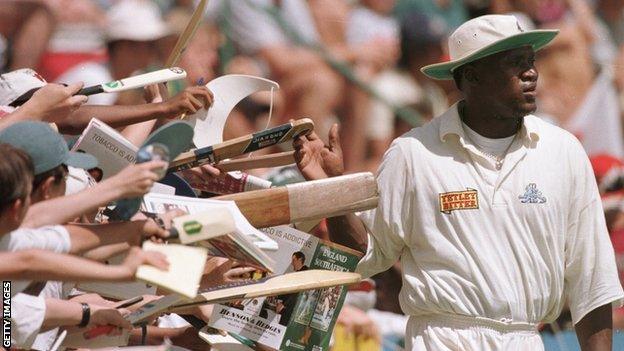

Fast bowler Devon Malcolm was born in Jamaica and played in 40 Tests for England, taking 128 wickets

Rainford-Brent says attracting Afro-Caribbean communities to play cricket has always been a problem.

Prior to Archer's recent inclusion, there have been 13 black cricketers to play for England who were born in the West Indies, including those big names from the 1990s such as Lewis, Malcolm and Gladstone Small.

"There's only a handful that have come through the system," Rainford-Brent says.

"I am not sure how much movement we have actually seen. I think it's consistently been in a state which needs some work and identification."

If the England team had a superstar who was black - like Archer could become, would we see a spike in participation from Afro-Caribbean communities?

Rainford-Brent thinks so, saying: "I have no doubt that if there was a black version of a Ben Stokes or Moeen Ali, he would a real role model who you could leverage to the maximum and really garner that excitement and support again."

Bell-Drummond offers a slightly different view.

"Michael Carberry had his go with the England team. Even though he would have had an impact, I don't think there will be hundreds of Afro-Caribbean kids coming into cricket because of him, or if I make it, because of me," he says.

Malcolm echoes Bell-Drummond, saying: "The main thing is getting the youngsters out there playing cricket.

"You can't say because of Moeen Ali you will have eight Asian players in a county team, that won't happen. But at the lower levels, in club cricket, you hope that these guys can influence kids to start playing the sport."

'Where black people are, black people will follow'

'My dream is to play Test cricket for England' - Jofra Archer speaking in 2018

Is Archer the future of English cricket therefore?

The 24-year-old was snapped up for £800,000 in the 2018 Indian Premier League auction, retained by the Rajasthan Royals for 2019 and has become a T20 sensation.

The all-rounder says he would love to "get to the top and encourage black kids" to play cricket.

Archer signed for Sussex in 2016 on the recommendation of England bowler Chris Jordan, also born in Barbados, after the two met in the Caribbean country.

Sussex have five black players in their first-team squad, more than any other county, and Archer says that was an influencing factor in him joining, despite Northamptonshire also offering him a trial.

"I pretty much only went to Sussex because of Jordan and the others. I much rather go somewhere where there are a few familiar faces," he said.

"I do think where black people are, black people will follow."

And that crystallises the challenge for all involved in English cricket - from the grassroots to the professional game.

- Published21 May 2019

- Published30 May 2019

- Published18 October 2019