Ruqsana Begum: Muay Thai world champion's difficult journey to the top

- Published

Muay Thai world champion. Dutiful daughter. Fastest girl in school. ME sufferer. Wife. Architect. It is difficult to categorise Ruqsana Begum.

Now aged 37, for much of her life she was caught between two worlds that could never meet. With two strings pulling on her in different directions, she was forced to keep each half of her identity separate, until both imploded and something new was forged from the debris left behind.

Today she lives in harmony with her difficult past. She has a bright, open smile as she warmly recounts her tale.

It is a twisting, turning story but if there is one dominant thread it might be this: the secret she once thought would ruin her turned out to be her saviour.

In the early days, there was only family.

There were nine of them in a three-bedroom flat in Bethnal Green. Begum in one room with her sister Farzana, then two grandparents, three brothers, and her parents who slept in the lounge.

They were one of many Bangladeshi families living in their council block and, according to Begum, "everyone knew everyone".

When she describes family life, it is through sounds.

It is her brothers downstairs, shouting as they play video games, her mother calling her to help in the kitchen or the chatter of her sister in bed at night.

"For many years, we were very compact and cosy but I loved it," Begum recalls.

"At the same time, you don't get your own space and it is hard to be creative and really flourish."

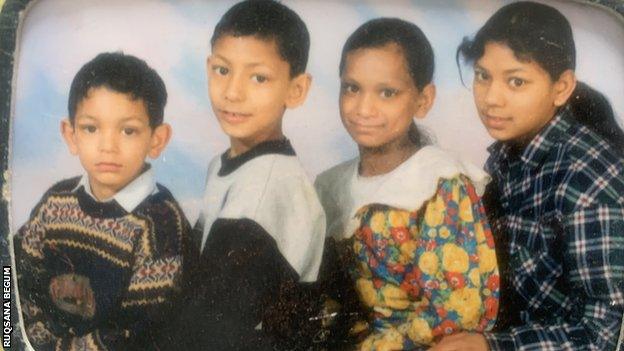

As a child, Ruqsana Begum (far right) lived in a Bethnal Green flat with eight other family members

Bruce Lee was Begum's first encounter with combat sports.

Her uncle Surath came to stay one night and was watching the martial arts icon on TV. A seven-year-old Begum was watching too, entranced by "this small man with yellow tracksuit bottoms".

"I was fascinated by his sheer skill, wisdom and speed," she says. "I just thought, 'When can I try this?'"

The answer to that question was complicated.

Begum already enjoyed sport. She took part in athletics and was the fastest girl at her school. She loved playing football too.

But when she turned 10, that all stopped. Begum was the eldest daughter in a traditional Muslim, Bangladeshi family and her mother was no longer happy with her going to the park to play with boys.

"My sister was allowed because she was younger, and my brothers were allowed too, but my mother would stop me from going," Begum explains.

"It was really restrictive and I used to feel so bored at home. I used to absolutely love playing football. That all came to an end as soon as I was 10. I was gutted."

Begum's interest in fighting would fester for another decade before she finally got her chance. Salvation came in the form of a poster advertising a kickboxing class at her school.

She went. It was straight after her lessons finished - minimal risk that her parents would find out.

Twenty years on from that first session, Begum's memories of how it felt are still visceral.

"It allowed me to be present," she says. "That was the main thing I took away from the session. It was fast, furious and exciting, it took me away from negative outputs in life.

"It was mentally, physically and emotionally challenging because I had to really focus my energy into the present moment. That is what I loved. The fact I was living life."

Begum had finally been given the chance to try a sport that had intrigued her since the age of seven, but it was immediately taken away. The session she attended was the last one. The school had run out of funding for the class.

Begum had been noticed, though, and the instructor invited her to train at his gym in a beginners' class at weekends. This would be difficult; an after-school class was fine, travelling to a gym at the weekend without her parents finding out was another matter entirely.

But Begum had had a taste and she could not turn back. So she stepped into another world.

Begum now talks nonchalantly of the time she - as a 5ft 3in 17-year-old whose universe had been a block of flats where she knew everyone - walked into a dark Muay Thai gym under the railway arches in Bethnal Green.

For many women of Begum's stature, walking into such a male-dominated environment might be intimidating. She does not dwell on that, perhaps because the real challenge was not in walking through the door. It was getting to the door.

She woke up extra early one Sunday. Her thinking was that if she spent all morning doing chores, she could ask to go out later in the day.

Begum told her mother she was going to the gym, but did not specify what kind of gym.

"I think she assumed I was going to a ladies' aerobics class," she says. "Given my background and just the fact I couldn't even go to my friend's house without having a valid reason, I knew going to the gym as an additional activity would not go down well with my parents.

"They wanted to see me live a very traditional life. They didn't want me to move away from what they had brought me up to be: a very ladylike female that is holding the house together and looking after the family. They had their own perception of what success is and what I should be adhering to."

Ruqsana Begum first tried Muay Thai at an after-school class

Nevertheless, Begum's mother let her out of the house and she did make it to the door of the gym.

Stepping inside was "quite scary", into a space full of what Begum describes as "highly testosterone-driven men".

"It was a very intimidating environment," she continues. "Lucky for me I didn't judge the sport based on that. I loved the sport itself."

For a long time Begum was able to balance the two halves of herself - kickboxing and family - without one ever meeting the other.

But five years after that first after-school session, the delicate balance she had weaved began to unravel.

In 2006 Begum, now 22, was coming to the end of an architectural technology degree at the University of Westminster.

She was in the library, working on a 10,000-word dissertation on damp-proof membrane and condensation in buildings, when she got the call.

Her parents had found a suitable husband.

An arranged marriage was something Begum had always seen in her future, but she hadn't expected it to come crashing into the university library quite so abruptly.

"I did want my father to give me a bit more time to establish myself in the field, work for a year and then get married," Begum explains. "But they came across someone that they really liked and they wanted to introduce me."

Begum agreed to an initial meeting but her main focus was still her degree. She would be moving in with her husband-to-be's family after the wedding and wanted time to get to know them all.

Before she knew it, the families had arranged an engagement party. Within six months she had graduated and was preparing for the wedding.

"Everything just got sped up and I couldn't even catch my breath," she says. "I felt I needed a moment to take it all in. Am I prepared for this? It seemed like everything was firing out of control and I didn't have a say anymore."

In her book, 'Born Fighter', Begum describes feeling a "rubber band" tightening around her stomach the night before her wedding.

She cried in the car from the wedding venue to her husband's house.

All those sounds that had meant home to Begum - her brothers, sister, mother - faded away and upon arriving with her new family she was met with silence.

On top of her day job as an architecture trainee, she was expected to cook, entertain guests and help care for her new father-in-law, who was on dialysis.

"I was quite isolated," Begum remembers. "I didn't really have anyone to talk to or to be friends with. I felt like I was just an extension helping them live their daily lives."

The trauma of such a dramatic life change was exacerbated by the fact that, in her new world, there was no room for fighting. The gym became a distant memory. Begum let that part of herself go and devoted her life to family - but it left her feeling "overwhelmed" and "lonely".

Something had to give and, after six months, it did.

Begum remembers it vividly.

The pressure of "trying to be everything to everyone" mounted and one morning, as she was helping her mother-in-law peel prawns, she fainted.

She was taken to hospital, where she remained for two days.

Afterwards she saw her GP, an Indian woman Begum felt could relate to her background and the expectations she was striving to live up to.

While in the doctor's office, Begum suffered a panic attack. The GP said it was the worst she had ever seen. Begum recalls: "She held my hand and said, 'You remind me of my daughter. Go back to your mum's to recuperate'."

She thought she would spend a couple of weeks recovering at her parents' house before returning to her marriage but her husband filed for divorce. Begum says jokingly she was "not really disappointed".

The stress did not subside, though. She was bedbound because of severe panic attacks, sometimes suffering 15 a day, with some just 20 minutes apart.

Begum says she was "exhausted" but also determined to change; "sick and tired" of feeling that way.

"I consider myself to be a fighter in life in general," she adds.

There was only one place her instincts would lead her.

It was the first time she had left the house since her divorce. Begum's parents - who had moved out of the flat in Bethnal Green by then - were travelling to east London and she asked if they would drop her off somewhere.

She says she had lost her identity and wanted to return to the only place she "felt at home and secure".

They pulled up in front of the familiar railway arches. Despite having spent years preventing her parents finding out what lay beyond the gym's doors, this time she invited them inside.

"I didn't know how they were going to react," she says. "I had no idea if they were going to be supportive or if they would lose their temper completely."

Begum's parents spoke to her coach Bill and were reassured.

"At that point I guess they really couldn't care less about me taking part in sport," she recalls. "They felt so guilty with me being so unwell."

With her parents now on board, Begum turned pro the following year. She finally began to fulfil all the potential she had shown in that first after-school session.

In 2009, she won bronze at the World Amateur Kickboxing Championships in Bangkok.

But she would have to make it through one more piece of adversity before reaching her peak.

In 2010, Begum had a shot at becoming the first Muslim woman to hold the Muay Thai British title.

Preparations were intense, but she felt more fatigued after training than she expected to. In fact, she felt she was not recovering from training sessions at all.

For the second time in her life, Begum found she just could not get out of bed, for weeks on end.

"There were days when I was so sharp in the ring and on fire," she remembers. "Then other days I couldn't even walk to the gym. I would come out of the Tube and struggle. I had cold sweats on my forehead and all over my back."

Eventually, Begum was diagnosed with ME, myalgic encephalomyelitis, also known as chronic fatigue syndrome.

This meant the vigorous training Begum was doing was leaving her with no energy. But the British title was still her focus, so she had to adapt.

Begum and her coach put fitness training to one side and focussed on strategy and technique.

It meant she could not truly know what she was capable of until stepping into the ring on the night of the biggest fight of her life. She "just hoped for the best" and it worked.

In November 2010, Begum beat Paige Farrington to be crowned British champion.

Six years later, she added world champion to her list of labels when she beat Susanna Salmijarvi on 23 April 2016 to take the World Kickboxing Association title.

In 2018 she made the switch to professional boxing and believes she can become a world champion in that discipline too, once the pandemic subsides enough to allow her to return to competition.

In boxing she has encountered people telling her she is the "wrong side of 30".

Begum's progress has been slowed but never halted by the many obstacles thrown in her path so far, so something as simple as age will surely not stop her.

Boxer is another on the long list of labels Begum could claim, but she now finally feels able to cast all those descriptors aside.

"Growing up I had all those boxes I felt I had to fit in to," she says.

"Now, finally, I feel empowered to just be me."

The Fight of the Century - Ali v Frazier: A ringside seat at the fight that changed the world

Stephen Merchant: Hello Ladies: Delivering the laughs in his brilliant live show