Tom Aspinall: UFC heavyweight talks about his son being autistic

- Published

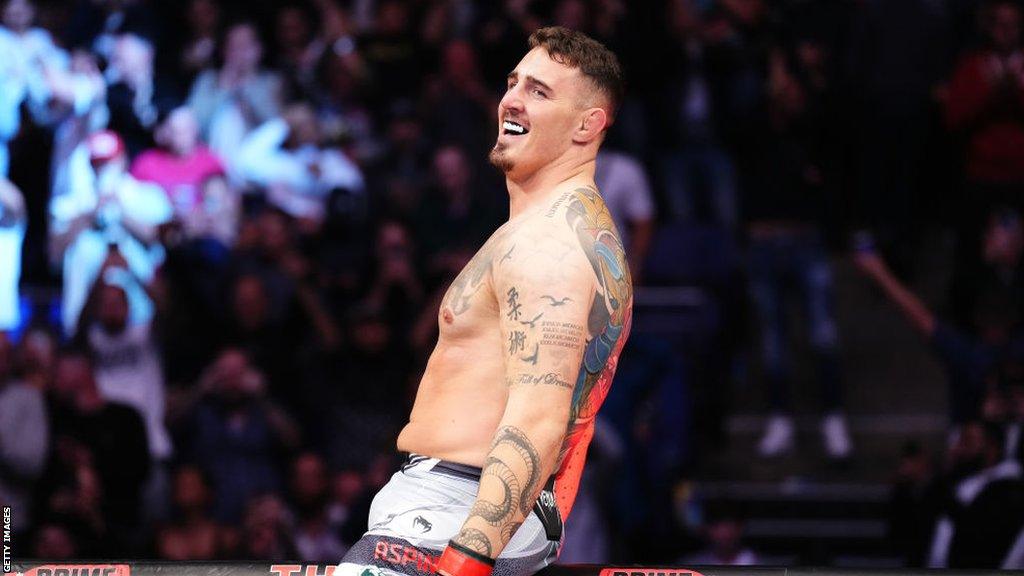

Tom Aspinall is a heavyweight star in the UFC and a father of three

"I didn't want there to be something wrong with my son. But when you start to learn about autism, you learn there's not something wrong with them. It's just a different way that their brains work."

UFC heavyweight contender Tom Aspinall is recalling the time one of his sons got an autism diagnosis - and says he was "in denial at first".

Inside the cage, Aspinall has the measure of a future world champion, but the 30-year-old is first and foremost a loving father to his eldest son, aged seven, and twin four-year-old boys.

In 2021, when the UK was under a coronavirus lockdown, one of the twins began to fall behind with speech and other key developmental milestones.

"We'd say his name and he would not look at you or make eye contact," says Aspinall, as he drives from his training base to the family home in Greater Manchester.

"If you told him off, he kind of wouldn't respond.

"I always was like: 'He'll catch up. He's just not as socialised as usual because of the lockdown.' Then I watched a programme with Paddy McGuinness."

The BBC documentary Paddy and Christine McGuinness: Our Family and Autism tells the story of television personality McGuinness' three autistic children.

By chance, Aspinall then had the opportunity to mention his son to McGuiness when they were booked on the same TV show.

McGuiness, who like Aspinall has three children including twins, admitted he was also reluctant to confront signs that his eldest child could be autistic - and his advice to Aspinall was clear: "Push for a diagnosis."

The National Autistic Society describes autism as a "lifelong developmental disability which affects how people communicate and interact with the world".

Typical symptoms may include difficulty communicating and understanding how other people think, an aversion to bright lights or loud noises, getting anxious about unfamiliar situations, and taking longer to understand information and doing or thinking the same things over and over.

Aspinall's son, who had demonstrated some of those traits, was assessed after his third birthday.

A year on, Aspinall speaks thoughtfully about his unique interactions with the world.

One in five people are neurodivergent, a term which celebrates those who are autistic, dyslexic, dyspraxic, have ADHD or another way of thinking.

"He's really social - he loves strangers," says Aspinall. "He'll go and sit on anybody's knee. I know some autistic children and they can't be around strangers at all. Every autistic person and child is completely different and you have to know their triggers and what sets them off.

"If there's something that's overwhelming for him, he won't communicate. He'll shut down straight away.

"Sometimes with autistic people, and children in particular, they are perfectionists, so if a toy, for example, isn't moving in the way that they want it to move, that can be the end of their little world."

Aspinall also says his son "doesn't understand danger".

"We were at my dad's surprise 60th at this beautiful house," he says. "They had a big lake there and he just went to jump straight in. Absolutely no hesitation."

Aspinall describes his understanding of autism as in its "infancy" but says he has a drive to use his platform as a mixed martial artist to increase awareness, understanding and acceptance, so people and parents of autistic children can feel empowered in public life.

"My kid doesn't understand making a mess and what's right and wrong, so he might get in a supermarket and start pulling stuff off the shelves," he says. "That's hard as a parent because you sometimes have people looking at you and you know they're thinking, 'will you sort your kid out?' If people were more aware, it would be a little bit easier."

How Aspinall went from £20 in the bank to headlining UFC

Aspinall also emphasises the importance of parents seeking a diagnosis if they have concerns.

The heavyweight fighter has witnessed improvements in his four-year-old son's ability to communicate and express emotions in the year following the diagnosis.

"He won't use speech to communicate as such," says Aspinall.

"He has a picture of different options he might want to snack on, so if he goes into the kitchen, he's got a picture of an apple, a banana, and a rice cake.

"Today he picked it up and pointed at what he wanted and said what he wanted. That is massive for us.

"And now when you say his name and then say 'can you give me a hug?' he'll run over and give you a hug and then go off and do whatever he's doing.

"It's absolutely massive because between the ages of two and three, he wouldn't even look at you or answer his name.

"And it just gives you hope moving forward."

If you have been affected by issues raised in this article, there is information and support available on BBC Action Line