LaShawn Merritt & Jessica Hardy target Olympic redemption

- Published

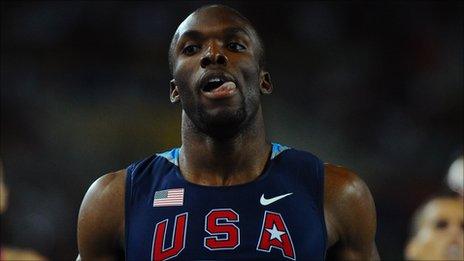

LaShawn Merritt determined to dominate 400m

Olympic 400m champion LaShawn Merritt is determined to put the controversy of his doping ban behind him and show the world his "dominance" at London 2012.

The American failed a drugs test in 2009, making him the first big name to fall foul of the International Olympic Committee's (IOC) "next Games" ban.

But Merritt overturned the ban at the Court of Arbitration for Sport (Cas).

"I didn't do anything wrong, I didn't intentionally do anything to cheat," said Merritt.

"I had something in my system, out of competition, that had nothing to do with track and field. I knew I was a great athlete and that when I was able to run again that wouldn't change."

Merritt, who dominated 400m running between 2008 and 2009, tested positive for a banned substance contained in an over-the-counter penis enlargement product.

As embarrassing as this was, it was nothing compared to the threat posed to his career.

Determined to protect the Olympic brand from growing cynicism about the prevalence of doping, the IOC imposed a tougher penalty for drugs cheats in 2008.

Rule 45 meant any athlete given a ban of six months or longer would also be barred from the next Olympics. This attracted little comment until Merritt's case started to work its way through the tribunal system.

A triple world junior champion in 2004, the Virginian was initially given the usual two-year ban prescribed by the World Anti-Doping Agency.

However, this was reduced to 21 months on appeal when Merritt - backed by the US authorities - was able to prove, in his own words, "no advantage gained, no intention to cheat".

The reduction in his ban meant the quarter-miler, still only 25, was able to go to the 2011 Worlds, where he was beaten into second place by Grenada's Kirani James.

Merritt did, however, claim gold as part of the USA's 4x400m team, and he also recorded the year's fastest time in the heats.

But it was not until October 2011, when Cas ruled in Merritt's favour, forcing the IOC to drop Rule 45, that he could think about defending his Olympic title.

This decision would take on added meaning for British Olympic sport as it set a precedent that ultimately brought down Team GB's lifetime doping ban.

Speaking at Team USA's London 2012 media summit in Dallas, Merritt blamed a lack of "caution" for his very public ordeal.

"I made an immature, poor choice," he said.

"It was as simple as not reading a label, not recognising an ingredient that's on a long list of substances that couldn't be in my system. There were a lot of times when I didn't know what would happen, or how my career would end up.

"But you know what? I had faith. I work hard to be great in this sport and I'll continue to work hard so I can go out and show my dominance - I'm still number one in the world."

Merritt is not the only American star eager to make the most of a second chance, although for Jessica Hardy this will be her first shot at Olympic glory.

The swimmer withdrew from the US team shortly before the Beijing Games when she stunned her team-mates by testing positive for a performance-enhancing drug in 2008.

This would normally carry a two-year ban but an American arbitration panel halved that in 2009 when she successfully demonstrated that she had been the victim of a contaminated nutritional supplement.

"The supplement industry in US isn't regulated at all, so every time somebody takes a supplement or vitamin they are putting themselves at risk," the world record-holder for the 50m and 100m breaststroke explained.

"And I think more athletes are doing that than we're aware of - it's scary. I would recommend against taking anything like that, it's not worth the risk."

Since her return, Hardy has emerged as a major contender for medals in London, and she goes to next month's US Olympic trials with a great chance of qualifying for the 100m breaststroke, freestyle sprints and relays.

"There was a time when I was angry and depressed about what happened," the 25-year-old Californian said.

"Being guilty until you can prove yourself innocent is a very difficult situation to be in, it's taxing mentally, physically and financially. But now I draw strength from it. I'm grateful that I get this chance again and I know I'm tougher than I thought I was.

"If you can prove it was inadvertent, and remove that doubt, then it's very unfair to keep people out of the Olympics."

- Published6 October 2011

- Published10 September 2015