Paula Radcliffe: Catching drug cheats a 'cat and mouse game'

- Published

Paula Radcliffe: 'The people who choose to dope are always going to be a little bit ahead of the testers'

For many endurance athletes training at altitude is their secret weapon.

We are 1,800m (6,000ft) above sea level in the Pyrenees, and marathon world record holder Paula Radcliffe is preparing for the London Olympic Games.

She is doing naturally what others turn to drugs for. Train this high, and the human body produces more of the hormone, EPO, erythropoietin.

The hormone stimulates the growth of red blood cells, which allows athletes to take on more oxygen, and their muscles to perform better.

Injecting EPO does the same thing, but is banned. And it is an approach she condemns, because it puts a question mark over every athlete and every outstanding performance.

"It's living with that doubt," says the 38-year-old mother of two, who won marathon gold at the 2005 World Athletics Championships.

"I've been in the position of having my performances doubted. It's wanting to be able to prove in some way that they were 100% clean.

"I know that inside, and that means a hell of a lot to me, but to be able to prove that would be great," she adds.

Radcliffe explains that the standard of drug testing is not quite at the level where everyone can believe in it.

The scientists on the trail of rogue athletes say they have made it harder to cheat.

Samples are now stored for eight years, so if any new test comes up, they can look back to see if an athlete was cheating in the past.

And then there is the biological passport. This is a snapshot of an athlete's physiology, and should stay constant over time. If it changes, that could be a sign of cheating.

But the science of doping is becoming more sophisticated, with the teams behind the cheats scouring science journals for clues to the next drug.

So is this a race the authorities can ever win?

"The doping system is very sophisticated," says Radcliffe.

"There are a lot of gains to be made from it, there's obviously financial involvement in that, and for a lot of the time the people who choose to dope are a little bit ahead of the testers - it is always going to be a chasing game."

So does she think that the latest testing regimes have made it any harder to cheat?

"It has definitely improved.

"At the same time, there are still athletes out there that still get away with cheating," says Radcliffe.

"I'm not naive enough to think there's nobody out there cheating now, there is. But there are a lot less than there were," she adds.

I ask her will there ever be a time when it is impossible to cheat?

"I'd love to see that happen.

"But I guess realistically the way science goes, it's always going to be a little bit of cat and mouse, but how close you can make that gap, whether you can make it close enough that there isn't really a window of opportunity there that people are going to take the risk with," she says.

Anti-doping stance

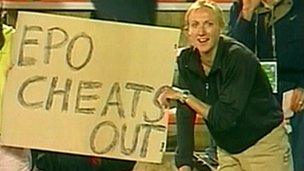

Radcliffe has spoken out about drugs in sport before. Back in 2001, she took a difficult decision to protest.

Paula Radcliffe protested about doping in sport during the 5000m at the Commonwealth stadium

Russian athlete Olga Yegorova had failed a drugs test before the world athletics championships, but was allowed to race.

"I'm very anti-doping, and really stand up against that, but I don't think I'm alone, " says Radcliffe.

"I think the majority of athletes feel that way, because we dedicate our lives to training hard, and to getting the best out of ourselves, and then to learn that one of your competitors might have taken an easier route is very frustrating," she adds.

Ten years later she says her strong anti-doping stance is about sticking to the values that keep her competing.

"My biggest goal and my biggest aim is that when I finish my career, I walk away and say 'okay that was the best I could do', and I know that that was everything that I could give and that was all I could do, and I want to be able to look back with pride," says Radcliffe.

"I want my children to be able to look at those performances and say 'mummy did that and she worked hard for that and daddy supported her all the way'."

Radcliffe adds that when you go to the start line and know you have worked really hard it is a very strong situation to be in.

"You can hold your head up high and you can dig deeper than someone who has taken a short cut."

You can see Susan Watts' report on drugs in sport on Wednesday 25th July 2012 on Newsnight at 10.30pm on BBC Two, and afterwards on BBC iPlayer and the Newsnight website.